6 Prescription Sleeping Pills and Women

Sydney Taggart

Introduction

The commonly known sleep recommendation for adults is at least seven hours per night (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2022). This recommendation has been proven necessary for optimal human functioning (Watson et al., 2015). However, as many as 33% of adults in the U.S. experience either occasional or constant insomnia and do not meet this recommendation (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2020). One way insomnia and sleeping problems are dealt with in the U.S. is by using prescription sleeping pills.

Prescription sleeping pills were first prescribed in the 1930s and reached an all-time usage high in the 1970s when benzodiazepines became the most commonly prescribed drugs in America (Wick, 2013). The three major classes of sleeping pills are barbiturates (barbs), benzodiazepines (benzos), and nonbenzodiazepines (Z drugs) (National Institute of Medicine, 1979). All three classes of sleeping pills affect the GABA receptor in the brain. They work by slowing down the central nervous system and promoting sleep (Brickley et al., 2018).

History of Prescription Sleeping Pills

Today, barbiturates are typically used only in hospitals to give anesthesia and treat seizure disorders. However, they were all the rage in the 1950s and 1960s. In New York City alone, there were 8,469 barbiturate overdoses and 1,165 deaths from 1957–1963 (López-Muñoz et al., 2005). In 1962, President Kennedy organized a drug-dependence committee to investigate the barbiturate epidemic. By 1965, more than 250,000 Americans were addicted to barbiturates. Barbiturates played a part in the deaths of many celebrities during this era, including Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, and Jimi Hendrix (Lathan, 2009; López-Muñoz et al., 2005).

In the 1960s, a benzodiazepine called Valium (diazepam) was introduced to the public (Herzberg, 2006). Valium was supposedly safer and less addictive than barbiturates, so many doctors started prescribing it instead of barbiturates. Valium became so popular in the 1970s that it became the single most prescribed medication in the United States for the entire decade (Herzberg, 2006). With more than 90 million bottles dispensed annually, a physician of the time claimed that the country would be in full-blown withdrawal should Valium become unavailable (Herzberg, 2006).

Women & History

The Valium epidemic had a particularly intense effect on women. The 1970s popularized Valium and other prescription drugs by advertising them as “Mother’s Little Helper” and “Woman’s Best Friend” (Metzl, 2003). Benzodiazepines were promoted as helpful for managing the pressures of marriage, motherhood, and other social pressures associated with womanhood. Middle-class white mothers, especially, were over-prescribed benzodiazepines and targeted by pharmaceutical companies in this era. A national survey conducted in the 1970s found that 20% of women reported having used Valium in the last five years, and 10% of those women reported regular use. These numbers were twice that of men (Herzberg, 2006). Women who expressed malaise, anxiety, or contempt for their lives as housewives were labeled hysteric and placated with sleeping pill prescriptions without consideration for dependence or adverse side effects. Benzodiazepines were the new wave, and they had women and mothers in their grip.

As benzodiazepines rose in popularity in the 1970s, there was a significant decrease in barbiturate prescriptions (Wick, 2013). This had both positive and negative effects. While the decrease in barbiturate use was positive and overdose numbers declined, the growing acceptance of benzodiazepines was potentially more dangerous. It took fifteen years after the introduction of benzodiazepines for physicians and researchers to realize that they could cause addiction and dependence (Wick, 2013). By the 1980s, clinicians recognized the similar risks created by benzodiazepines and barbiturates (Wick, 2013).

The 1990s marked the introduction of Z drugs such as zolpidem (Ambien), zaleplon, and eszopiclone (Brandt & Leong, 2017). A 1983 U.K. study found that, compared to benzodiazepines, Z drugs were associated with fewer overdose fatalities. This means that there were fewer deaths by Z drugs than there have been with benzodiazepines. However, that does not mean that Z drugs come without risk. Several studies have shown that Z drugs, like barbiturates and benzodiazepines, are associated with an increased risk of car accidents and falls involving bone breaks due to drowsiness. Extreme memory loss is also a common side effect of using Z drugs. Because Z drugs are relatively new, little research has been conducted on their addiction rates. While they are a better alternative to benzodiazepines, there is always a risk of becoming dependent on sleep medications (Brandt & Leong, 2017; Lie et al., 2015; Schifano et al., 2019).

Women Today

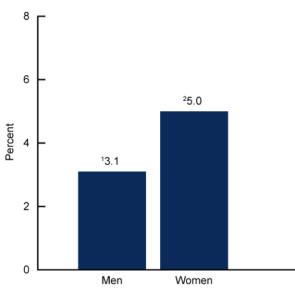

The prescription sleep aid crisis continues to affect women at higher rates (CDC, 2023). Today, women are 1.3 times more likely to have insomnia-related sleep problems than men and, on average, only sleep about 6.5 hours per night (Hislop & Arber, 2003). This discrepancy in sleep quality between sexes is thought to contribute to women’s increased use of prescription sleeping pills compared to men (CDC, 2023). In a 2020 study, women were found to be over 50% more likely to use prescription sleeping pills than men and are thus at higher risk for misuse and overdose (CDC, 2023; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2022). This difference is likely due to the environmental and social circumstances that cause women to sleep less and have their sleep interrupted more than men ( Graham & Vidal-Zeballos, 1998; Hislop & Arber, 2003). Women with children report much worse sleep quality and more frequent awakenings during the night than their male partners. Unequal child-care burdens may also contribute to some women using prescription sleep aids (Härdelin et al., 2021). Additionally, pregnancy presents a number of physical and hormonal challenges that impact sleep quantity and quality (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 2023 [MFMER]).

Women may also metabolize sleep medication slower than men. In a study testing zolpidem (Ambien) blood levels eight hours after taking the medication, women were found to have much higher blood levels of the medication than men after the same dosage and time (Yale School of Medicine, 2016). In 2013, the FDA reduced the recommended dosage of Ambien for women by half due to reported morning drowsiness and the risk of car accidents due to drowsy driving. Sex differences in the metabolization of medication are a very recent discovery. Standard dosages are typically based on male metabolism, which may be responsible for the disproportionate adverse effects in women (Stachenfeld & Mazure, 2022).

The Future of Women’s Health & Sleep Aids

In the history of prescription sleeping pills, it is important to note that rates of benzodiazepine use dropped from 16.5 million prescriptions in 1991 to 13.2 million in 2000 (Hislop & Arber, 2003). This number continues to trend downward, indicating that women are finding healthier solutions for their sleeping issues or becoming more involved in their medical care (Lie et al., 2015). Researchers hope that an increased focus on co-parenting and the promotion of sleep hygiene is playing a role in this decrease in benzodiazepine prescriptions. However, this decline may simply be due to the new era of Z drugs.

While prescription sleeping pills are still prescribed to many patients, science and medical research continue to evolve and improve the medications available for sleep regulation. The current recommendation for prescription sleep aids is that they be used for short periods for acute stress, trauma, travel, or other temporary situations (MFMER, 2022). For long-term sleep management, behavioral methods, like reducing distractions before bed and being physically active during the day, are generally the best treatment.

Conclusion

Prescription sleeping pills should be used sparingly and as a last resort. Women, especially, should be cautious about prescription sleeping pills, as they are more at risk for abuse and overdose (CDC, 2023). The current guidelines for prescribing drugs for insomnia-related sleep problems strongly caution against prescription sleep aids and recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy as a co-prescription to sleeping pills (Sateia et al., 2017). If drug therapy is necessary, Z drugs are the first recommendation.

Review Questions

1. What are the three classes of prescription sleeping pills?

a. Barbituates, ambien, & z drugs

b. Barbituates, benzodiazepines, & z drugs

c. Diazepam, benzodiazapines, & nonbenzodiazepines

2. Who has a higher risk for sleeping pill abuse?

a. Men

b. Women

c. Men & women have equal risk

3. What class of prescription sleeping pills has the lowest risk of overdose?

a. Barbituates

b. Benzodiazepines

c. Z drugs

References

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2020). Provider fact sheet – insomnia. https://aasm.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ProviderFS-Insomnia.pdf

Brandt, J., & Leong, C. (2017). Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs: An updated review of major adverse outcomes reported on in Epidemiologic Research. Drugs in Research & Development, 17(4), 493–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-017-0207-7

Brickley, S. G., Franks, N. P., & Wisden, W. (2018). Modulation of GABA : A receptor function and sleep. Current Opinion in Physiology, 2, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cophys.2017.12.011

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, September 14). How much sleep do I need? https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/how_much_sleep.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, January 25). Sleep medication use in adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db462.htm#Key_finding

Graham, K., & Vidal-Zeballos, D. (1998). Analyses of use of tranquilizers and sleeping pills across five surveys of the same population (1985–1991): The relationship with gender, age, and use of other substances. Social Science & Medicine, 46(3), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00168-8

Härdelin, G., Holding, B. C., Reess, T., Geranmayeh, A., Axelsson, J., & Sundelin, T. (2021). Do mothers have worse sleep than fathers? Sleep imbalance, parental stress, and relationship satisfaction in working parents. Nature and Science of Sleep, 13, 1955–1966. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.s323991

Herzberg, D. (2006). “The pill you love can turn on you”: Feminism, tranquilizers, and the valium panic of the 1970s. American Quarterly, 58(1), 79–103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068349

Hislop, J., & Arber, S. (2003). Understanding women’s sleep management: Beyond medicalization-healthicization? Sociology of Health and Illness, 25(7), 815–837. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9566.2003.00371.x

Kripke, D. F., Klauber, M. R., Wingard, D. L., Fell, R. L., Assmus, J. D., & Garfinkel, L. (1998). Mortality hazard associated with prescription hypnotics. Biological Psychiatry, 43(9), 687–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00292-8

Lathan, R. S. (2009). Celebrities and substance abuse. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 22(4), 339–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2009.11928552

Lie, J. D., Tu, K. N., Shen, D. D., & Wong, B. M. (2015). Pharmacological Treatment of Insomnia. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 40(11), 759. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4634348/

López-Muñoz, F., Ucha-Udabe, R., & Alamo, C. (2005). The history of barbiturates a century after their clinical introduction. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 1(4), 329-343. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2424120/

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2022, September 16). Prescription sleeping pills: What’s right for you? https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/insomnia/in-depth/sleeping-pills/art-20043959

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2023, February 21). How many hours of sleep do you need? https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/expert-answers/how-many-hours-of-sleep-are-enough/faq-20057898

Metzl, J. M. (2003). ‘Mother’s little helper’: The crisis of psychoanalysis and the miltown resolution. Gender History, 15(2), 228–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.00300

Institute of Medicine. 1979. Sleeping Pills, Insomnia, and Medical Practice: Report of a Study. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9934

National Library of Medicine. (2022, November 18). Barbiturates – statpearls – NCBI bookshelf. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539731/

Sateia, M. J., Buysse, D. J., Krystal, A. D., Neubauer, D. N., & Heald, J. L. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: An American academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(02), 307–349. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6470

Schifano, F., Chiappini, S., Corkery, J. M., & Guirguis, A. (2019). An insight into Z-drug abuse and dependence: An examination of reports to the european medicines agency database of suspected adverse drug reactions. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 22(4), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyz007

Stachenfeld, N. S., & Mazure, C. M. (2022). Precision Medicine requires understanding how both sex and gender influence health. Cell, 185(10), 1619–1622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.012

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, May 4). Sex and gender differences in substance use. National Institutes of Health. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/substance-use-in-women/sex-gender-differences-in-substance-use

Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D. F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M. A., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R. K., Martin, J. L., Patel, S. R., Quan, S., & Tasali, E. (2015). Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the american academy of sleep medicine and sleep research Society. Sleep. 38(6). 843-844. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4716

Wick, J. Y. (2013). The history of benzodiazepines. The Consultant Pharmacist, 28(9), 538–548. https://doi.org/10.4140/tcp.n.2013.538

Yale School of Medicine. (2016, February 15). Sex and the science of testing meds: You don’t know the half of it. https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/sex-and-the-science-of-testing-meds-you-dont-know-the-half-of-it/

having trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or getting good quality sleep

core chemical structure is a benzene and diazepine ring; a depressant drug that helps with anxiety, muscle spasms, sleep, and reduces seizures

derived from barbituric acid; a depressant drug used to help sleep, relieve anxiety and muscle spasms, and prevent seizures

A newer class of sedative drugs whose effects are similar to benzodiazepines but whose structure is different

a type of brain receptor that blocks impulses between nerve cells in the brain

a temporary loss of feeling with or without a loss of awareness

causing a strong and harmful need to regularly have to do something

the unpleasant physical and mental symptoms experienced when someone stops taking an addictive drug, such as sweating, anxiety, vomiting, and depression

general feeling of discomfort, illness, or uneasiness without a known cause

a strong feeling of disliking and having no respect for someone or something

excessively emotional or dramatic

physically needing a drug to function

a chronic, physiological or psychological dependence on a drug or activity despite its harmful effects

deaths

to be used by body cells

amount of medication

a structured, goal-oriented type of talk therapy used to treat conditions such as addictions