14 The Rise in Prescription Stimulant Misuse

Sullivan Bishop

Introduction

Stimulant medications, such as amphetamines, are typically prescribed to treat those with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, also known as ADHD. Stimulants work by increasing the levels of dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). By doing so, stimulants reduce many common symptoms seen in those with ADHD. They heighten focus, improve mood, and manage hyperactivity. While they have been prescribed since the 1930s, within the past decade, the access to stimulants has significantly increased and can be attributed to heightened prescription rates (Brumbaugh et al., 2022). This poses a risk for misuse of these medications across various populations in the United States. Misuse of stimulants can create drug dependency and detrimental health effects. As of 2010, improper use of prescription stimulants has become an epidemic in the United States (Ahmed et al., 2022).

Background

In the 1880s, a German scientist, Lazar Edelenau, synthesized amphetamines (Rasmussen, 2015). In 1932, the drug became popularized when an American chemist, Gordon Alles, began searching for a better asthma medication than those on the current market. Amphetamines did not treat the symptoms of asthma as anticipated. However, they increased energy levels, so they were remarketed as an antidepressant (Rasmussen, 2015).

After many clinical trials, amphetamine effects were better understood. Psychiatrists began prescribing them for various disorders in the 1940s (Rasmussen, 2015). The trial results found that stimulants’ side effects proved hopeful for treating children with behavioral disorders (Connolly et al., 2015). By the 1950s, amphetamines were found to reduce hyperactivity and boost productivity levels. Once ADHD was recognized as a mental disorder, stimulants were prescribed as the first line of treatment. (Connolly et al., 2015).

As the popularity of stimulants rose, so did the risk of misuse. Throughout the 1960s, amphetamines were marketed for various treatments, including weight loss supplements, decongestive medication, antidepressants, and anti-sleep medications (Rasmussen, 2008). These marketing tactics targeted a wide spread of people, and soon, 149.4 million Americans were taking these drugs daily. Studies began to emerge, claiming that amphetamines could be addictive. In the 1970s, health organizations began prioritizing public health issues that originated from the Vietnam War, such as substance abuse. Due to the increased misuse of amphetamines, the BNDD restricted the accessibility of stimulants and classified them as a Schedule II drug (Rasmussen, 2008). Even with this restriction, the number of stimulant prescriptions continued to rise over the decades. In the 1990s, about 0.6% of people had a prescription. By 2015, the percentage rose to 6.6%; of those, five million reported misusing their medication at least once (NIH, 2020). As of 2012, America has the highest rate of stimulant prescriptions (Weyandt et al., 2016).

Amphetamine abuse continues to grow, and those addicted face serious health concerns. This epidemic is unique because stimulants’ effects attract a variety of people for different reasons. Some misuse stimulants recreationally in addition to other ‘hard drugs’, while others use them to improve their academic performance. Stimulants have become readily available in America. In some environments, it has also increased the number of potential sellers seeking to make a profit (Ahmed et al., 2022). The rise in their abuse and prescribing jeopardizes the American population’s health.

The Popularity of Prescription Stimulant Misuse (2010-2020)

Since 2010, young adults (18-25 years old) are the most likely to abuse stimulants (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011). In 2015, 14.1% of young adults admitted to misusing stimulants, which can be attributed to the rise in prescriptions (Hughes et al., 2016). In 2010, Ritalin was the most popular medication prescribed to adolescents (Kennedy, 2018). Researchers soon discovered that college students have the highest percentage of stimulant abusers compared to any other young adult population. It is estimated that 20% of college students habitually misuse these medications (Kennedy, 2018). This subset includes people buying prescription stimulants and those already prescribed amphetamines.

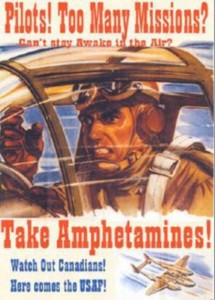

Many students will obtain these medications by asking a relative, friend, or buying them from peers. The motivations behind amphetamine abuse vary across this population. The most common reason is to enhance their academic performance by being able to stay up later to study, increasing their productivity, and/or improving their overall concentration (Edinoff et al., 2022). Other reasonings include the desire to experience a high (2-13%), self-treating undiagnosed ADHD (4-12%), and an appetite suppressant (3.5-11.7%) (Edinoff et al., 2022). Many reasons for abuse in the 21st century have stayed the same since the mid-1900s. In World War II, soldiers abused amphetamines to stay awake during combat, and now students misuse them to stay awake to study (Rasmussen, 2008). Women in the 1960s took stimulants to lose weight, and women in college today abuse these drugs for the same reason (Rasmussen, 2008).

Amphetamine abuse is also present among adolescents and older adults. In 2022, around 9.2% of middle and high school-aged students admitted to misusing amphetamines (NIH, 2023). Adolescents’ motivation for abuse includes coping with mental health disorders and stresses in life, boredom, or to experiment (University of Rochester Medical Center, 2023). Abuse is uncommon in older adults (45+) as they tend to misuse other substances like alcohol.

Health Risks Related to the Misuse of Stimulants

Many young adults abusing prescription stimulants are not aware of the dangers they possess. Amphetamines can be addictive when people with a prescription take higher dosages than recommended or when they are consumed by those without a prescription (National Library of Medicine, 2022). This can create a dependency where users require a higher or more frequent dosage to experience the same effects (National Library of Medicine, 2022).

Amphetamine abuse can cause cardiac issues, elevated blood pressure, insomnia, anxiety, agitation, hallucinations, and mood fluctuations (Mayo Clinic, 2022). The number of hospital visits because of amphetamine misuse has almost doubled from 2006 to 2011 (Aubrey, 2016). Consuming too high of a dose can increase the chances of an overdose (Osborn, 2023).

Conclusion

The misuse of prescription stimulants has been a health concern since the mid-1900s, particularly in young adults. Overprescribing these medications makes them more accessible, and awareness of risks is low. With more people taking amphetamines, availability decreases for those with ADHD, which can generate shortages (Food and Drug Administration, 2022). Abuse of these drugs jeopardizes the public’s health and puts those prescribed at a disadvantage. Substance abuse not only impacts the individual, but it can negatively affect relationships or an entire community. In order to reduce the popularity of its misuse, prevention programs can be implemented. Education and awareness campaigns about misuse and prescription monitoring programs are two key ways to improve this epidemic. Interventions must be implemented so individuals can understand the risks related to stimulant misuse or the frequency of improper amphetamine use will continue to grow.

Review Questions

1. What schedule drug are prescription stimulants currently classified as?

a. Schedule I

b. Schedule II

c. Schedule III

d. Schedule IV

2. True or false: Globally, America is the leading stimulant prescriber.

a. True

b. False

3. What age group misuses prescription stimulants the most?

a. Middle school-aged students (11-14)

b. Young Adults (18-25)

c. Adults (26+)

d. Elders (65+)

References

Ahmed, S., Sarfraz, Z., & Sarfraz, A. (2022). Editorial: A changing epidemic and the rise of opioid-stimulant co-use. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.918197

Aubrey, A. (2016, Feb 16)Misuse of ADHD Drugs by Young Adults Drives Rise in ER Visits. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/02/16/466947829/of-adhd-drugs-linked-to-increased-er-hospital-visits-study-finds.

Brumbaugh S., Tuan W.J., Scott A., Latronica J.R., Bone C. (2022) Trends in characteristics of the recipients of new prescription stimulants between years 2010 and 2020 in the United States: An observational cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 50. 101524 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(22)00254-1/fulltext.

Cleveland Clinic (2022, Oct 6) ADHD medications: How they work & side effects. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/11766-adhd-medication.

Connolly, J. J., Glessner, J. T., Elia, J., & Hakonarson, H. (2015). ADHD & pharmacotherapy: Past, present and future: A review of the changing landscape of drug therapy for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 49(5), 632–642. https://doi.org/10.1177/2168479015599811

Edinoff, A. N., Nix, C. A., McNeil, S. E., Wagner, S. E., Johnson, C. A., Williams, B. C., Cornett, E. M., Murnane, K. S., Kaye, A. M., & Kaye, A. D. (2022). Prescription stimulants in college and medical students: A narrative review of misuse, cognitive impact, and adverse effects. Psychiatry International, 3, 221–235. DOI: 10.3390/psychiatryint3030018

Food and Drug Administration. (2022, Oct 12). FDA announces shortage of adderall. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-announces-shortage-adderall.

Hughes, A., Williams, M.R., Lipari, R.N. Bose, J. Copello, E.A.P., & Kroutil, L.A. (2016, Sept.) Prescription drug use and misuse in the United States: Results from the 2015 national survey on drug use and health. SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR2-2015/NSDUH-FFR2-2015.htm

Kennedy S. (2018). Raising awareness about prescription and stimulant abuse in college students through on-campus community involvement projects. Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education. 17(1), A50–A53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6312145/.

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2022, Oct.) Prescription drug abuse. Mayo Clinic https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prescription-drug-abuse/symptoms-causes/syc-20376813.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2020, June 3). Five million american adults misusing prescription stimulants. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/2018/04/five-million-american-adults-misusing-prescription-stimulants.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2023, Feb 13). What Is the scope of prescription drug misuse in the United States?. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/misuse-prescription-drugs/what-scope-prescription-drug-misuse#:~:text=An%20estimated%200.7%25%20of%208th,in%20the%20past%2012%20months.

Osborn, C.O. (2023, Feb 3) Treating amphetamine overdose: Stimulant drug overdose. Recovery.org. https://recovery.org/amphetamine/overdose/.

Rasmussen, N. (2015). Amphetamine-type stimulants: The early history of their medical and non-medical uses. International Review of Neurobiology, 120, 9-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2015.02.001

Rasmussen N. (2008). America’s first amphetamine epidemic 1929-1971: a quantitative and qualitative retrospective with implications for the present. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 974–985. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.110593

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2011). Results from the 2010 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHNationalFindingsResults2010-web/2k10ResultsRev/NSDUHresultsRev2010.pdf.

National Library of Medicine. (2022, Apr). Substance use – Amphetamines. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000792.htm

University of Rochester Medical Center. (2023). Teens and prescription medicines. Health Encyclopedia. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=1&contentid=4240#:~:text=Teens%20abuse%20prescription%20medicines%20for,or%20simply%20to%20get%20high.

Weyandt, L. L., Oster, D. R., Marraccini, M. E., Gudmundsdottir, B. G., Munro, B. A., Rathkey, E. S., & McCallum, A. (2016). Prescription stimulant medication misuse: Where are we and where do we go from here?. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24(5), 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000093

Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Neurological disorder associated with inattention and hyperactivity.

Neurotransmitters - Signaling chemicals secreted by neurons in the brain

used to alleviate depression

Type of scientific research that studies new treatments and their effects on human health and behavior.

Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. Today it is called the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Medications that require a physician’’s approval each time they need to be filled.

Highly addictive drugs that cause users to have severe psychological dependence. EX) Heroin, cocaine, GHB, etc.

A common prescription stimulant medication

Diseases related to the heart or blood vessels. Ex) Heart attack or heart palpitations

having trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or getting good quality sleep

Feeling of fear and/or dread associated with the anticipation of a future event.

when a person consumes an amount of a drug that is more than what should be taken at one time, possibly leading to serious health concerns and death