16 Medical Guidelines for Prescribing Drugs Post-Surgery in Adolescents

Elizabeth Tomkovich

The Opioid Epidemic and Its Impact on Adolescents

Opioids are drugs that have been used for pain management since the 1800s (Rivat & Ballatyne, 2016). Extract from the opium poppy was used therapeutically for many centuries at low doses with few negative effects (Rivat & Ballatyne, 2016). In the 20th century, scientific understanding of opioids led to increased clinical use by physicians, which led to more prescriptions at higher doses (Rivat & Ballatyne, 2016). Likewise, adding pain as a “fifth vital sign” has led to increased opioid medication consumption (Cochran et al., 2022). Currently, opioids have been reformulated to be long-lasting, with continual administration, and target broad ranges of pain (Rivat & Ballatyne, 2016). Opioid medication sales in the United States have increased by 150% between 1997 and 2007 (Cochran et al., 2022). Since 2000, the number of overdose deaths involving prescription opioids has quadrupled (Bass et al., 2020).

Pharmaceutical companies have also played a role in the prescription patterns of physicians. They invest tens of millions of dollars into marketing drugs to physicians (Hadland et al., 2019). These marketing efforts have caused an increase in the number of prescriptions which have led to higher mortality rates (Hadland et al., 2019). Pharmaceutical companies have pushed drugs on doctors, claiming they were not addictive, to improve profits. By promoting and distributing opioids, pharmaceutical companies received large cash bonuses (Cochran et al., 2022). The change in the use of opioids and aggressive pharmaceutical marketing has led to an increased risk of adverse outcomes.

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the opioid epidemic (Bass et al., 2020). Often, a child’s first exposure to opioids is after a surgery (Bass et al., 2020). Some studies have found that surgeons often over-prescribe opioids after surgery to avoid inadequate pain control in patients (Horton et al., 2019). The number of opioids prescribed often exceeds the necessary amount needed for adequate pain relief (Neuman et al., 2019). In the pediatric surgical population, pain management is complicated by perceived lower pain tolerance and difficulty determining pain level (Horton et al., 2019). The patient’s family may encourage the ingestion of pills to follow the doctor’s orders even though the child may not be in a high amount of pain. Adolescents are at risk for errors in opioid prescription, inadequate pain control, and persistent opioid misuse (Horton et al., 2019).

Prescribing Opioids Post-Surgery in Adolescents

Post-surgical prescription has led to opioid-related complications (Horton et al., 2019). The main risk factor for prescription opioid misuse is exposure to opioids in early childhood and adolescence (Bass et al., 2020). The earlier someone is exposed, the greater their risk of developing a prescription opioid misuse disorder (Bass et al., 2020). The original intent of the drug was for pain management, but people have begun to use the drug to get high. A survey of 12th-grade students showed a 33% increase in opioid misuse following prescribed use (Bass et al., 2020). The misuse could lead to addiction due to the immaturity of the brain (Bass et al., 2020). The adolescent’s brain develops the limbic region (the risk-taking area of the brain) before the cortex region (the critical thinking portion of the brain). Teens engage in risk-taking behaviors without fully understanding the consequences. This disconnect can result in motivation to start using drugs for reasons other than pain management (Winters & Arria, 2012). Young adults, ages 18-25, are responsible for the most significant amount of opioid abuse, with addiction rates six times higher in 2014 than in 2001 (Bennett et al., 2019).

Adverse Outcomes

The main adverse outcomes among adolescents include opioid misuse, diversion, opioid use disorders, and overdose (Neuman et al., 2019). Unused prescriptions can lead to diversion (Neuman et al., 2019). Excess pills stored in homes are a target for family members, friends, or other parties (Neuman et al., 2019). An association has been found between youths with an opioid use disorder and a greater lifetime substance abuse disorder, intravenous drug use, and increased mental illness (Yule et al., 2018). In the past twenty years, these outcomes have increased the number of deaths among adolescents (Abraham et al., 2019).

Current Laws

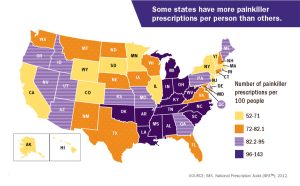

In response to the opioid crisis in the US, states and the federal government have begun implementing policies to curtail the effects. Currently, five states have a “continuing medical education requirement” (Mauri et al., 2019). This policy requires physicians to receive postgraduate training in opioid prescribing and addiction (Mauri et al., 2019). Twelve states require the regulation of pain management clinics to manage and treat chronic pain (Mauri et al., 2019). Forty-one states adopted opioid prescribing guidelines (Mauri et al., 2019). These guidelines may include opioid selection, dosage, or duration, but there is variability within states (Mauri et al., 2019). All fifty states prohibit patients from receiving drugs by fraud or misrepresentation (Mauri et al., 2019). Drug supply management policies have been created to restrict the amount or dosage that can be prescribed (Mauri et al., 2019). Despite the large number of policies, states have full control over what is implemented. Variations between states can lead to differences in prescribing patterns and patient care.

Solutions

Pharmaceutical companies have become a part of the rehabilitation process. Pharmacies have created take-back programs where individuals can drop off “unused” medications to prevent inappropriate disposal and diversion (Cochran et al., 2022). The American Pharmacist Association (APA) focuses on naloxone training and education (Cochran et al., 2022). They support the education of pharmacists and patients and the creation of a law to permit pharmacists to provide naloxone (Cochran et al., 2022). The APA also advocates for screening and assessing patients for possible non-medical use of prescription opioids (Cochran et al., 2022). The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists recommends the development of curricula in pharmacy training programs and universities (Mauri et al., 2019). These educational, training, and resource efforts are collectively working together to combat the opioid epidemic.

Current attempts to reduce opioid overprescribing include educating healthcare providers and families and increasing the utilization of non-narcotic pain medications (Bass et al., 2020). Prevention efforts should consider that most adolescents misusing opioids receive these drugs from friends or family members (Hudgins et al., 2019). When prescribing opioids to families with children, proper disposal methods should be included in the counseling process (Bass et al., 2020). One study found that providing patients with a brochure describing how to dispose of opioids increased the frequency of patients who disposed of leftover medication (Neuman et al., 2019). Providers must educate patients and families on the importance of taking medication properly, clear guidelines on when to use the medication and the risks associated with diversion (Yule et al., 2018). Providers can also encourage adolescents who have been prescribed opioids to access naloxone (Yule et al., 2018). If an adolescent does develop a substance use disorder, healthcare providers should screen them for additional substance use and create a plan of intervention (Hudgins et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Overall, prescribing opioids after surgery leads to an increased risk of opioid misuse in the adolescent population. New guidelines are evolving to transform the way physicians order opioids to prevent the development of opioid misuse, diversion, and opioid use disorders among adolescents. Adolescents who are exposed to opioids early on in life will have an increased risk of opioid consequences. Public health officials must continue to examine educational opportunities and policies to curb the opioid epidemic.

Review Questions

1. What is the number one contributor to adolescents’ exposure to opioids?

a. Peers

b. Physician prescriptions

c. School

d. Family Members

2. Why are prescribing patterns of physicians contributing to opioid misuse in adolescents?

a. Physicians often overprescribe opioids

b. Physicians underutilize over-the-counter drugs like Tylenol or Advil

c. Marketing pressure from pharmaceutical companies

d. All of the above

3. What is not an adverse outcome that can occur from exposure to opioids in adolescents?

a. Opioid misuse

b. Pain control

c. Overdose

d. Opioid diversion

References

Abraham, O., Thakur, T., & Brown, R. (2019). Prescription opioid misuse and the need to promote medication safety among adolescents. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(7), 841-844 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.01.003.

Bass, K. D., Heiss, K. F., Kelley-Quon, L. I., & Raval, M. V. (2020). Opioid use in children’s surgery: Awareness, current state, and advocacy. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 55(11), 2448-2453 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022346820301160.

Bennett, K. G., Harbaugh, C. M., Hu, H. M., Vercler, C. J., Buchman, S. R., Brummett, C. M., & Waljee, J. F. (2018). Persistent opioid use among children, adolescents, and young adults after common cleft operations. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 29(7), 1697 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6173989/.

Cochran, G., Hruschak, V., DeFosse, B., & Hohmeier, K. C. (2016). Prescription opioid abuse: pharmacists’ perspective and response. Integrated Pharmacy Research and Practice, 65-73 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/IPRP.S99539.

Horton, J. D., Munawar, S., Corrigan, C., White, D., & Cina, R. A. (2019). Inconsistent and excessive opioid prescribing after common pediatric surgical operations. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 54(7), 1427-1431 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022346818304317.

Hudgins, J. D., Porter, J. J., Monuteaux, M. C., & Bourgeois, F. T. (2019). Prescription opioid use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the United States: A national survey study. PLoS Medicine, 16(11), e1002922 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002922.

Mauri, A. I., Townsend, T. N., & Haffajee, R. L. (2020). The association of state opioid misuse prevention policies with patient‐and provider‐related outcomes: a scoping review. The Milbank Quarterly, 98(1), 57-105 https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12436.

Neuman, M. D., Bateman, B. T., & Wunsch, H. (2019). Inappropriate opioid prescription after surgery. The Lancet, 393(10180), 1547-1557 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673619304283.

Paulozzi, L. J., Budnitz, D. S., & Xi, Y. (2006). Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 15(9), 618-627 https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1276.

Pruitt, L. C., Swords, D. S., Russell, K. W., Rollins, M. D., & Skarda, D. E. (2019). Prescription consumption: Opioid overprescription to children after common surgical procedures. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 54(11), 2195-2199 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.04.013.

Ward, A., De Souza, E., Miller, D., Wang, E., Sun, E. C., Bambos, N., & Anderson, T. A. (2020). Incidence of and factors associated with prolonged and persistent postoperative opioid use in children 0 to 18 years of age. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 131(4), 1237 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7723784/.

Winters, K. C., & Arria, A. (2011). Adolescent brain development and drugs. The Prevention Researcher, 18(2), 21 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3399589/.

Yule, A. M., Lyons, R. M., & Wilens, T. E. (2018). Opioid use disorders in adolescents—updates in assessment and management. Current Pediatrics Reports, 6, 99-106 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40124-018-0161-z.

made in a different way

recurring steadily

to give remedially

a written direction for medicine

A class of drugs primarily used for pain relief that is derived from or mimics the chemical structure of substances found in the opium poppy plant (Opioids, 2022).

the total capacity of enduring unpleasant bodily sensations

incorrect or improper use

a medical condition characterized by a pattern of prescription opioid use that causes impairment or distress (Neuman et al., 2019).

entering by way of vein

a synthetic potent antagonist of narcotic drugs