13 Approaches to Supporting Families Through Divorce

Abbie Flanigan and Isabella Kruse

This chapter is based on the Social Ecological Model.

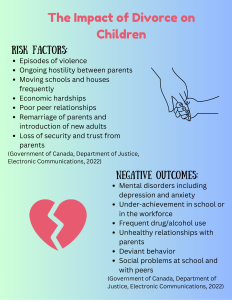

Many children have parents who get divorced, and it can be really tough on families. About 40-50% of first marriages end in divorce, according to the American Psychological Association, and the rate is even higher for second marriages (Previtera, 2022). The effects that divorce can have on a child are varied, however some of the most common results include attachment issues, social withdrawal, behavioral problems, and an increased risk of mental health problems such as anxiety and depression (University of Illinois Chicago, 2023). In some cases, children of divorced parents may be more prone to engaging in risky sexual behavior, alcohol addiction, face a higher likelihood of living in poverty, and experience future instability in their own family relationships. In fact, the risk is 1.5 to 2 times higher for children of divorced parents compared to those with married parents (D’Onofrio and Emery, 2019). The impacts of parental divorce can continue throughout adulthood (Rhodes et al., 2021). However, existing solutions and coping mechanisms can help mitigate the negative consequences surrounding divorce for at-risk children.

Individual

Several current preventive interventions have shown positive effects on how a child adjusts to the divorce of their parents. One child-focused program, Children’s Support Group (CSG), emphasizes the importance of developing coping skills, building social support, and recognizing one’s emotions (Rhodes et al., 2021). The CSG program showed positive results in boosting self-esteem, social skills, and reducing adjustment problems in children and early adolescents, with benefits continuing for a year after the program (Rhodes et al., 2021).

Furthermore, parents also face their own challenges during divorce and can use supportive programs to help deal with these problems. The Parenting Through Change (PTC), a group program for mothers, targets parenting practices, emotion regulation, and managing internal conflict. Similarly, the Dads for Life (DFL), a program for fathers, aims to strengthen a father’s dedication to his roles, help him feel more in control of divorce-related situations, and enhance his skills in parenting or managing conflicts. Experimental trials have shown that both programs helped reduce internal conflicts and difficulty adapting (Rhodes et al., 2021).

Relationship

The relationship level can be used to develop intervention strategies that target the interactions between the child and their parents when dealing with divorce. For example, the New Beginnings Program (NBP) strives to improve the quality of parent-child relationships, promote effective discipline, and address conflicts between parents (Rhodes et al., 2021). After a 15-year follow-up of the NBP, researchers found that this program had positive effects on work success, peer competence, social relationships, and academic performance for children. NBP has increased positive family activities, improved listening skills, and increased the consistency of rules at home (Rhodes et al., 2021). Families have strengthened their relationships by working on improving the listening skills for both children and parents (Rhodes et al., 2021). Listening skills help create an environment of trust, support, and understanding with family members and peers. For families dealing with divorce and facing challenges that come with it, having someone who listens can make a significant difference in their well-being.

Another successful support program for children of divorce is the Children in Between (CIB) program. This short, online program for parents aims to improve communication skills while minimizing children’s exposure to conflict (Melin and Nichols, 2013). The CIB program provides an expert-driven curriculum that is both affordable and accessible to families, as it contains 100% online classes that can be accessed at any time and from any location where the parent feels comfortable (The Center for Divorce Education, 2024). Through several modules, the course targets different aspects of co-parenting. The modules include interactive activities aimed at teaching effective communication, managing emotions, and offering practical advice on creating a stable environment for children during the challenges of divorce (The Center for Divorce Education, 2024). Overall, this program addresses family-related issues, with the main goal being to help parents manage conflicts in a way that benefits the entire family across different stages of life.

Community

School and community intervention programs can help children cope with the negative impacts of divorce and improve the emotional and academic outcomes of children of divorce. First, the Children of Divorce Intervention Program (CODIP) is an intervention program delivered to children ages 5-14 who are experiencing parental separation and divorce (National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices [NREPP], 2025). The intervention has been implemented in schools, community centers, and healthcare facilities (NREPP, 2025). The program’s primary goal is to minimize the behavioral and emotional problems children experience following parental divorce (Pedro-Carroll et al., n.d.). CODIP focuses on three major topics: children’s feelings related to divorce, coping skills, and emotional regulation (NREPP, 2025). School faculty or parents can recommend children to the program, which consists of 12-15 group sessions led by trained leaders. The program has four versions, each tailored to a specific age group (Pedro-Carroll, n.d.). Early sessions use books and films to address divorce-related feelings. The second part focuses on helping children differentiate between what they can and cannot control. The final portion addresses anger and divorce-related emotions through role-playing (NREPP, 2025). Six different clinical trials reported that the program benefited children. Parents, teachers, and children reported improved coping skills, communication, and problem-solving abilities (Pedro-Carroll, n.d.). For more information on the CODIP program, visit this link.

Additionally, school counselors and teachers can be understanding and help support these children during this difficult period. Teachers and counselors are often the first to notice signs of distress in children (Mahmud et al., 2011). Because children lack the coping skills to process their emotions, a trained school therapist may be an option for support for these children. Creative interventions, including art and play therapy, assist children in expressing their feelings rather than keeping them inside. Communication and collaboration between the school counselors, teachers and parents can help children effectively cope during this uneasy time (Mahmud et al., 2011).

Also, the eNew Beginnings Program (eNBP) is an online program designed to help parents reduce the negative effects of divorce on their children. It focuses on four key objectives: doing fun family activities, learning effective listening skills, establishing family rules, and learning tools to manage conflict with ex-partners (Arizona State University, n.d.). The eNBP is accessible and interactive, with modeling videos, exercises, and feedback from previous patients. Both parents and children reported improved discipline, parent-child relationships, and reduced conflict between parents (Arizona State University, n.d.). The eNBP models the in-person New Beginnings Program (NBP), which has shown improved parenting and reduced rates of mental health problems in children whose parents participated. Over 80% of participants believe courts should recommend eNBP (Arizona State University, n.d.). For more information on the eNBP, visit this link.

Societal

Courts recognize the negative effects of parental conflict on children during divorce, so many courts mandate parental education classes. Seventeen states require education classes for all divorcing parents, regardless of whether the divorce is uncontested(Divorce Writer, n.d.). The rest of the states either leave parental education to the judge’s discretion or only mandate it in certain counties (Divorce Writer, n.d.).

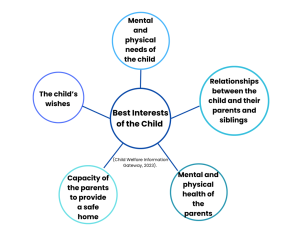

In high-conflict divorce cases, courts prioritize the child’s “best interests”. Most states lack a set definition of the “best interests of the child,” but legal experts generally understand the concept (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2023). About 31 states list specific factors regarding the best interests of the child in their statutes (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2023). While the factors vary from state to state, commonly required factors include the relationships between the child and their parents, siblings, or other caregivers, the capacity of the parents to provide a safe home, and the mental and physical needs of the child (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2023). By focusing on the child’s best interests, courts make choices that support the child’s well-being during the challenges of divorce.

Key Takeaways

- While parental divorce can have serious and lasting negative effects on children (mental health challenges, behavioral issues, future relationship instability, etc.), evidence-based interventions, such as the CSG, can help children build coping skills, improve self-esteem, and reduce adjustment problems.

- Relationship-level interventions, such as the NBP and CIB, play a vital role in helping families navigate the challenges of divorce by improving parent-child relationships, enhancing communication skills, and reducing conflict.

- Programs like the school-based CODIP help children process emotions, develop coping skills, and reduce behavioral issues following divorce. Online programs like eNBP support parents by promoting positive discipline, communication, and emotional connection with their children.

- Many courts now require or encourage parental education classes and use “the best interests of the child” standard to guide custody decisions to reduce the harmful impacts of divorce on children.

References

Arizona State University. (n.d.). eNew beginnings program. Research and Education Advancing Children’s Health Institute. https://reachinstitute.asu.edu/programs/new-beginnings#:~:text=The%20eNew%20Beginnings%20Program%20

Arkes J. (2015). The Temporal Effects of Divorces and Separations on Children’s Academic Achievement and Problem Behavior. Journal of divorce & remarriage, 56(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2014.972204

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2023). Determining the best interests of the child. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/resources/determining-best-interests-child/

The Center for Divorce Education. (2024, May 28). Children in between class. https://divorce-education.com/classes/children-in-between-class/#:~:text=Crafted%20by%20Dr.,part%20of%20their%20divorce%20proceedings.

Divorce Writer. (n.d.). Divorce parenting classes: state requirements. https://www.divorcewriter.com/parent-education-class-divorce

D’Onofrio, B., & Emery, R. (2019). Parental Divorce or Separation and children’s Mental Health. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 100–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20590

Government of Canada, Department of Justice, Electronic Communications. (2022). Children’s responses and adjustment to parental separation and divorce – voice and support: Programs for children experiencing parental separation and divorce. Justice.gc.ca. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/fl-lf/divorce/2004_2/p2.html

Mahmud, Z., & Yee Pek, Y., & Rafidah, A., & Amla, S., & Salleh, A. (2011). Counseling children of divorce. World of Applied Sciences. 14, 21-27. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=ef31f908df72732feb1199b446cdb9ecde682161

Mellin, E. A., & Nichols, L. M. (2013, December). Divorce and children. American Counseling Association Practice Beliefs. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/practice-briefs/divorce-and-children.pdf?sfvrsn=a66da370_1

National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices. (2025). Children of divorce intervention program (CODIP). https://www.nreppadmin.net/viewintervention_id_220.html#:~:text=The%20Children%20of%20Divorce%20Intervention,of%20parental%20separation%20and%20divorce

Pedro-Carroll, J. (n.d.). Children of divorce intervention program. Children’s Institute. https://www.childrensinstitute.net/programs-services/children-divorce-intervention-program-codip

Pedro-Carroll, J., Alpert-Gillis, L., & Sterling, S. (n.d.). Children of divorce intervention program. Children’s Institute. https://www.childrensinstitute.net/sites/default/files/documents/codip_grades_2-3.pdf

Previtera, P. (2022). Divorce statistics. https://www.petrellilaw.com/divorce-statistics-for-2022/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20American%20Psychological,second%20marriages%20ending%20in%20divorce.

Rhodes, A., O’Hara, K., Velez, C., & Wolchik, S. (2021, February). Interventions to help parents and children through separation and divorce. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/divorce-and-separation/according-experts/interventions-help-parents-and-children-through-separation

University of Illinois, Chicago. (2023, February 22). The effects of divorce on Children & How to Help Them Cope. Department of Psychiatry. https://www.psych.uic.edu/research/community-based-children-and-family-mental-health-services-research-program/in-the-news/the-effects-of-divorce-on-children-how-to-help-them-cope#:~:text=Divorce%20may%20have%20many%20effects,unwanted%20health%20outcomes%20in%20adulthood

Children engaging in behaviors that meet the social goals of the child and that are appropriate for the social context.

Both sides agree on a desired outcome, but are using the court system to make their agreement legally binding.