23 Eating Disorders

Jordyn Carroll

Introduction

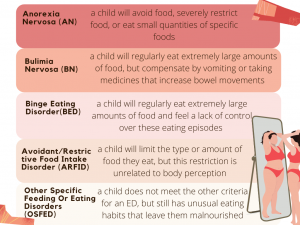

Eating disorders (EDs) are defined by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) as “illnesses that are associated with severe disturbances in people’s eating behaviors and related thoughts and emotions” (NIMH, 2021). These “disturbances” can take on many different forms, depending on the type of eating disorder. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) places feeding and eating disorders (FEDs) into specific categories. The NIMH describes common ED categories, which are summarized below:

Common Risk Factors

Demographics

Approximately 5.7% of girls and 1.2% of boys have eating disorders (Erriu, 2020). Non-Hispanic white individuals are more likely to report an ED than Hispanic and non-Hispanic black individuals (O’Brien, 2017). Trans-gender, [pb_glossary id="1816"][pb_glossary id="1816"]non-binary, and gender diverse youth are more likely to exhibit ED symptoms when compared to cisgender youth, which could be due to gender-related issues (Coelho, 2019). Individuals who report traumatic events or food insecurity (click here to learn more about food insecurity) in childhood are also more likely to report an ED (O’Brien, 2017). Although it has been shown that symptoms occur evenly across education and income levels, stereotypes depict EDs as “wealthy white female” diseases (Mulders-Jones, 2017). This assumption can limit other groups from accessing and learning about treatment options (Huryk, 2021). EDs are also more common in adolescent athletes when compared to non-athletes (Mancince, 2021).

Sports that place importance on lean body types, high-intensity training regiments, pressure from coaches, and early dieting and training can make youth particularly vulnerable (Patel, 2003). Because some children only participate in a sport for only a short timeframe, it is difficult to determine if these sports increase EDs. Nevertheless, prolonged female sports like gymnastics, running, swimming, and male weight-class sports like boxing and wrestling increase EDs in adulthood (Sanda, 2012).

Body Image

Body dissatisfaction is the strongest predictor of disordered eating behaviors in children (Voelker, 2015). When someone is unhappy with their body, it can lead to reduced ideas of self-worth (self-esteem) and negative feelings like depression. Social media plays a large role in influencing an adolescent’s perception of beauty. Males are often pressured to be bigger and more muscular, while females are encouraged to have thin bodies (Uchoa, 2019). Children exposed to media are more likely to have body-altering surgeries and develop eating disorders (Voelker, 2015). When a child is unable to replicate media images of beauty, they feel body dissatisfaction. In fact, studies show that the biggest decrease in body satisfaction happens in girls under the age of 19 after viewing images of underweight women (Voelker, 2015). These females were 2.4 times more likely to report having an ED (Mancine, 2020).

Genetics and Family Relationships

Family, twin, and genome-wide association studies consistently show that genetics play a major role in EDs (Himmerich, 2019). However, parenting styles and attitudes can put a child at risk of an ED. Overprotective and absent father figures have been correlated to eating and body concerns in their adolescents (Horesh, 2020). Mothers who are highly anxious or display negative forms of affection (anger or sadness) can also increase a child's risk of developing an ED (Tafia, 2017). Stereotypical parenting patterns that contribute to EDs are an intrusive and hypercritical female guardian and an intelligent, yet absent male figure. Outside of this family model, other parenting styles can increase the risk for an ED. To learn more about how parenting styles can influence a child, please visit this book's chapter on parenting styles.

Physical Impact of Eating Disorders

Eating disorders can cause stunted bone growth, puberty delays, and weakness (Eating Disorders, 1998). Specific effects of the three most common eating disorders are described below:

What Can You Do?

Knowing common signs and symptoms is a great first step as a caregiver. Common behavioral signs of EDs include dieting, skipping meals, and/or noticeably controlling food. Children with EDs may have a preoccupation with food and weight, develop food rituals, refuse to eat certain foods or whole food groups, and may even feel uncomfortable eating around others. Additionally, social indicators of EDs may include withdrawal from social groups. To learn about the physical signs related to eating disorders, please reference NEDA's factsheet.

Children will mirror the habits they see in their parents. By using positive language about one’s own body, a caregiver can improve their child's body perception. This can be accomplished by modeling balanced meals, explaining the weight-related aspects of puberty, talking about media messages, and placing value on personality, rather than weight or size (Mayo Clinic, 2022).

Having open and honest conversations about ED signs can change the course of a child's ED journey. For tips on how to approach an eating disorder conversation, reference this helpful graphic below:

Resources

Because eating disorders can be life-threatening, it is crucial to know what steps to take if a child begins showing signs. If an ED is suspected, speaking with a specialist can confirm a diagnosis and get a child the help they need. Management of eating disorders through a treatment plan that combines multiple avenues of care is ideal. Treatments may involve speaking with a psychologist, meal planning, and in some instances, hospitalization. Below are some helpful resources for accessing ED information, treatment options, and current awareness initiatives.

- HelpGuide

- The HelpGuide outlines the necessary steps in eating disorder treatment and recovery.

- National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA)

- Along with providing ED education, NEDA can help caregivers to find virtual or in-person doctors and treatment centers nearby.

- Multi-service eating disorder association (MEDA)

- MEDA provides an online recovery support group for ED sufferers and their families.

- The Body Positive

- The Body Positive is one of many organizations that address the role body image plays in EDs. This program promotes healthy body image through online programs.

- The Eating Disorder Coalition (EDC)

- The EDC is a group of people who promote eating disorder awareness at the governmental level.

Key Takeaways

- A child’s relationship with food and weight impacts them both mentally and physically.

- Eating practices can become disordered due to various demographic, heritable, interpersonal, and environmental risk factors.

- Caregivers have the potential to positively shape an adolescent’s self-concept by recognizing disordered tendencies. Caregivers can also proactively model positive body and food talk while openly communicating with a child.

- Ultimately, some children will develop EDs, but accessing resources at the community level through outpatient and collaborative treatment can help a child create a healthy relationship with their mind, body, and eating.

References:

Bratland-Sanda, S. & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2013). Eating disorders in athletes: Overview of prevalence, risk factors and recommendations for prevention and treatment. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(5), 499-508. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.740504

Canadian Paediatric Society. (1998). Eating disorders in adolescents: principles of diagnosis and treatment. Paediatrics & child health, 3(3), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/3.3.189

Coelho, J. S., Suen, J., Clark, B. A., Marshall, S. K., Geller, J., & Lam, P. (2019) Eating disorder diagnoses and symptom presentation in transgender youth: a scoping review. Current Psychiatry Reports. 21, 107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1097-x

Erriu, M., Cimino, S., & Cerniglia, L. (2020). The role of family relationships in eating disorders in adolescents: a narrative review. Behavioral Sciences, 10(4), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10040071

Himmerich, H., Bentley, J., Kan, C., & Treasure, J. (2019). Genetic risk factors for eating disorders: an update and insights into pathophysiology. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125318814734

Horesh, N., Sommerfeld, E., Wolf, M., Zubery, E., & Zalsman, G. (2020). Father-daughter relationship and the severity of eating disorders. European Psychiatry, 30(1), 114-120. https://doi.org/10.1016 /jeurpsy.201 4.04.00

Huryk, K. M., Drury, C. R., & Loeb, K. L. (2021). Diseases of affluence: a systematic review of the literature on socioeconomic diversity in eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101548

Mancine, R., Kennedy, S., Stephan, P., & Ley, A. (2020). Disordered eating and eating disorders in adolescent athletes. Spartan Medical Research Journal, 4(2), 11595. https://doi.org.10.51894/001c.11595

Mayo Clinic (2022). Healthy body image: tips for guiding teens: healthy lifestyle tween and teen health. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/tween-and-teen-health/in-depth/healthy-body-image/art-20044668

Mulders-Jones, B., Mitchison, D., Girosi, F., & Hay, P. (2017). Socioeconomic correlates of eating disorder symptoms in an Australian population-based sample. PLoS ONE, 12(1) e0170603. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170603

National Institute of Mental Health (2021). Eating disorders. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders

National Eating Disorder Association. (2022a). Health consequences. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/warning-signs-and-symptoms

National Eating Disorder Association. (2022b). Warning signs and symptoms. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/warning-signs-and-symptoms

O’Brien, K. M., Whelan, D. R., Sandler, D. P., Hakk, J. E., & Weinberg, C. R. (2017). Predictors and long-term health outcomes of eating disorders. PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0181104. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181104

Rienecke R. D. (2017). Family-based treatment of eating disorders in adolescents: current insights. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics, 8, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S115775

Tafà, M., Cimino, S., Ballarotto, G., Bracaglia, F., Bottone, C., & Cerniglia, L. (2017). Female adolescents with eating disorders: parental psychopathological risk and family functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0531-5

Voelker, D. K., Reel, J. J., & Greenleaf, C. (2015). Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: current perspectives. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics, 6, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S68344

a handbook that is used by doctors in the United States to diagnose psychiatric illnesses/disorders

noting or relating to a person who's gender identity does not match their sex determined at birth

noting or relating to a gender identity that does not align with male or female divisions

noting or relating to someone who's gender identity does not align with socially defined female or male norms

a prescribed course of medical treatment, way of life, or diet for the promotion of or restoration of health

these studies rapidly scan markers across complete sets of DNA, or genomes, to find the genetic variations that are associated with a particular disease

meticulously or excessively critical

a specialist in the science of the mind, mental states, or mental processes