16 LGBTQIA+ Youth

Aisling Hillman

Introduction

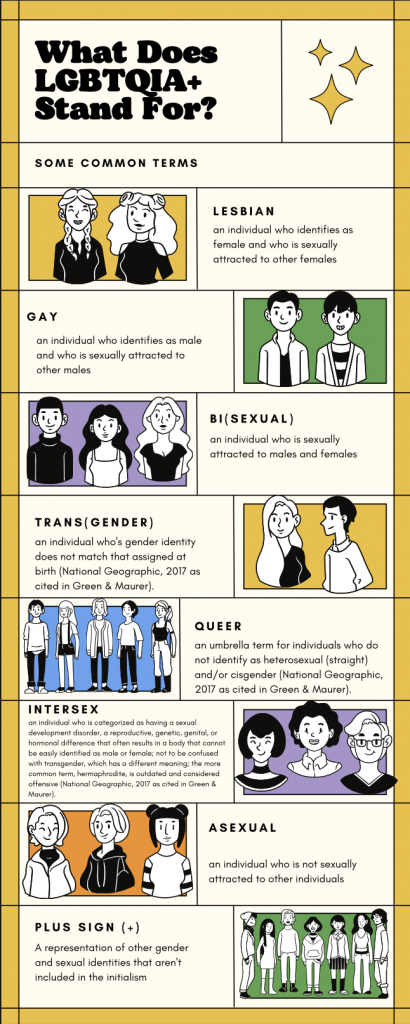

In recent years, gender and sexuality movements have gained awareness as new policies work to decrease the minority pressures LGBTQIA+ individuals face. When talking about gender and sexuality, it is key to understand that each is a fluid spectrum. An individual’s gender identity may remain static and aligned with their assigned sex at birth. It also may be fluid, shifting between “girl,” “boy,” or anywhere in between. To respect the individual, be aware of their preferred name and pronouns (he/she/they or him/her/them) (Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). While gender refers to a person’s self-identity and representation, sexuality refers to a person’s sexual orientation. Sexuality, much like gender, may also be viewed as a spectrum. Common terms to describe one’s sexual orientation are: lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, and/or asexual.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), several risk factors are associated with identifying as LGBTQIA+, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts/actions. Most research on LGBTQIA+ youth focuses on the associated risk factors. Recent research has begun to look at protective factors, which have shown promising results among bullied youth; however, more research is needed to better understand which factors may be protective for queer youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

Risk Factors

Studies have linked bullying experiences to increased risk of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts/actions (Johns et al., 2020). According to STOMP Out Bullying (n.d.), a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the lives of students, 9 out of 10 LGBTQIA+ students reported having been bullied or harassed. In the 2019 report of the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 33% of LGB youth said they were bullied compared to 17% of heterosexual students (Johns et al., 2020). The comparisons are alarming.

Minority stressors can be external or internal. External stressors (e.g., violence, discrimination, or harassment) and internal stressors (e.g., hiding one’s identity or expectations of rejection) can influence both mental and physical health. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) found that 23% of LGB youths had attempted suicide, whereas five percent of heterosexual students had attempted suicide (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). Not all LGBTQIA+ will experience poor mental health, but these individuals are at an increased risk of developing such issues due to the minority stressors placed on them (Fulginity et al., 2021). Knowing the warning signs and keeping an open line of communication decreases high rates of poor mental health.

Protective Factors

Recently, some protective factors have been identified (CDC, 2019; Gorse, 2022). It is understood that supportive families and an accepting environment may help to improve the well-being of LGBTQIA+ youth (Rafferty, 2021). Another potential protective factor is a safe and accepting school environment (Rafferty, 2021). In recent years, more districts have implemented programs to create a safer, more inclusive environment for LGBTQIA+ youth.

Other important protective factors are the creation of and participation in gay-straight alliances (GSAs), LGBTQIA+ inclusive curriculums, LGBTQIA+ affirming policies in schools, positive family and peer support, and possible interventions by the school and health professionals if necessary (Gorse, 2022).

Resources

Research indicates that programs implementing strength-based approaches and positive youth development programs, which focus on building protective factors, could be particularly beneficial for LGBTQIA+ youth (CDC, 2019). Many programs target school-level interventions.

- Safe and Supportive Schools Project

- Created by the American Psychological Association (APA), this program focuses on three strategies to improve schools.

- Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs)

- School clubs that can help provide a safe space for queer students and support from cis, heterosexual peers and encourage cultural sensitivity among the student body (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021; CDC, 2019; Gorse, 2022).

- Under the Equal Access Act, schools that allow “non-curricular” student organizations are legally required to allow the creation of a GSA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021).

- Family Acceptance Project (FAP)

- FAP, conducted by San Francisco State University, is a model to target ethnically, religiously, and racially diverse families as well as help to encourage acceptance of their LGBTQIA+ children.

Key Takeaways

- Gender and sexuality are both fluid spectrums of identity.

- LGBTQIA+ youth are more likely to experience bullying and negative mental health outcomes than their cis, heterosexual peers.

- Supportive family and safe school environments are protective factors for queer youth.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2021, December 16). Health concerns for gay and lesbian teens. Healthychildren.org. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/teen/dating-sex/Pages/Health-Concerns-for-Gay-and-Lesbian-Teens.aspx

American Psychological Association. (2014). Safe and supportive schools project. https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/programs/safe-supportive

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, December 20). Protective factors for LGBTQ youth: Information for health and educational professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/disparities/protective-factors-for-lgbtq-youth.htm?CC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fhealthyyouth%2Fdisparities%2Flgbtprotectivefactors.htm

Fulginity, A., Rhoades, H., Mamey, M. R., Klemmer, C., Srivastava, A., Weskamp, G., & Goldbach, J. T. (2021). Sexual minority stress, mental health symptoms, and suicidality among LGBTQ youth accessing crisis services. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(5), 893-905. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1007/s10964-020-01354-3

Gay-Straight Alliance Network (2022). What is a GSA Club? https://gsanetwork.org/what-is-a-gsa/

Gorse, M. (2022). Risk and protective factors to LGBTQ+ youth suicide: A review of the literature. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 39(1), 17-28. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1007/s10560-020-00710-3

Green, E. & Maurer, L. (2017). A Portrait of gender today. National Geographic 231(1), 12-13.

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Haderxhanaj, L.T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., & Suarez, N. A. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students- Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015-2019. US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2019/su6901-H.pdf

Rafferty, M. (2021, December 16). Gender-diverse & transgender children. Healthychildren.org. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/gradeschool/Pages/Gender-Diverse-Transgender-Children.aspx

San Francisco State University. (n.d.) Family Acceptance Project. https://familyproject.sfsu.edu/overview

STOMP Out Bullying. (n.d.). LGBTQ+ bullying. https://www.stompoutbullying.org/lgbtq-bullying

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (n.d.). Federal laws. Stopbullying.gov. https://www.stopbullying.gov/resources/laws/federal

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, September 10). LGBTQI+ youth. Stopbullying.gov. https://www.stopbullying.gov/bullying/lgbtq

the way an individual perceives themself

or heterosexuality; sexual desire or behavior directed toward a person or persons of the opposite sex

in reference to queer individuals, minority stress is the mechanism in which society may direct stigmas against this group

characteristics, conditions, and/or behaviors that help to reduce the negative effects of risks, stress, and/or trauma

also cisgender[ed]; noting or relating to a person whose gender identity corresponds with that person's sex assigned at birth