7 Socioeconomic Status

Sydney Langley

Introduction

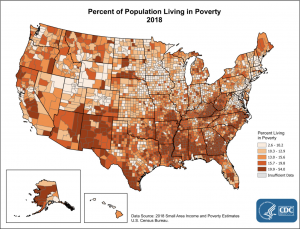

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a measure that includes parental education, marital status, employment, household income, and eligibility for government aid (Letourneau et al., 2011). In 2019, the official poverty rate was 10.5%, which is the lowest-known percentage since 1959 (Friedrich, 2021). Although this rate is improving, a low socioeconomic status can lead to health issues for children. Socioeconomic status can take a toll on family well-being, mental health, physical health, and education.

Family Well-Being

Low SES can hurt the quality of relationships between family members. Parents living in poorer conditions have more psychological and economic stress (Jia et al., 2021). Economic stress is the feeling of stress due to their current financial status. When economic stress occurs in the family, conflict and aggression are more likely to occur. Children are more likely to have less self-control when they witness this aggression, which can increase the likelihood of taking unnecessary risks. The lack of parental support and supervision can lead to dangerous behaviors such as smoking, drinking, violence, and crimes that could harm long-term psychological and physical health (Jia et al., 2021). High poverty neighborhoods are more likely to have crime and violence, more illegal drugs, and negative adult role models. A study conducted by Johns Hopkins found that children ages 7 to 12 experienced more behavior problems if they lived in a neighborhood their parents considered “poor” for raising children (Benham, 2017). Family income is the most important factor in determining the quality of settings such as home life, neighborhoods, and schools. If these settings are harmful rather than supportive, it decreases adolescents’ chances for success in adulthood (Escarce, 2003).

Mental Health

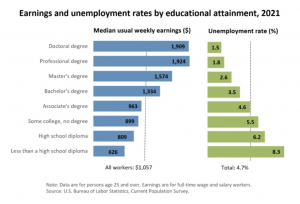

One of the health issues facing children is low mental health, which means the way that children feel, think, and relate to others every day is at risk of being damaged. Children with low SES are at a greater risk of having behavioral problems than children with a higher status (Letourneau et al., 2011). For example, early childhood exposure to negative situations can lead to poor mental health in the future (Hosokawa & Katsura, 2018). Children with lower SES are more likely to be subjected to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), such as abuse or household dysfunction (Knifton & Inglis, 2020). The stress associated with living in a low-income household can put a strain on mental health (2021). The effects of low SES can cause children to develop two types of behavioral outcomes: internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Internalizing form includes anxiety and depression, while externalizing behaviors result in hyperactivity and aggression (Letourneau et al., 2011). A study found increased rates of externalizing and internalizing behaviors among poor children than in more well-off children. When these behaviors extend into adulthood, it can make educational and job opportunities more challenging, which makes it more difficult to escape the cycle of poverty (Comeau & Boyle, 2018).

Physical Health

Children of lower SES demonstrate higher rates of physical health issues and increased risk of long-term chronic diseases. According to Dowd et al. (2009), there is a higher reported rate of diseases like asthma or other respiratory conditions among children with a lower status. One reason for these high rates could be the increased exposure to toxic environments such as lead paint and pollution (Chen, 2004). Children of lower SES are more likely to be exposed to pollution due to living near factories or major roads (Mathiarasan & Hüls, 2021). When children with these conditions are repeatedly untreated, their immune system weakens, which increases the likelihood of developing chronic conditions later in life (Dowd et al., 2009). Lack of access to healthcare and insurance may prevent children from receiving treatment. Additionally, low SES kids tend to get less physical activity due to safety concerns and access to outdoor activities (Chen, 2004). Decreases in physical activity can contribute to obesity, leading to negative health outcomes. Children in more wealthy neighborhoods have been found to have lower obesity risks and physical inactivity levels than those in less income neighborhoods (Singh & Ghandour, 2012).

Education

Along with psychological and physical health, studies have found that students with low SES have higher dropout rates and lower enrollment rates in high schools and colleges (Hosokawa & Katsura, 2018). The quality of education children receive is related to their SES. Since many low-income areas of the country are underfunded, children do not receive the same quality of education as students with higher status (American University, 2020). Parents in families with low SES, especially single-parent households, may not have the resources after work to devote to their children and their education (Jia et al., 2021).

Resources

There are many programs designed to help low-income families when it comes to education, housing, food access, and health insurance. Below are a few of the many available resources:

- Child Care and Development Fund

- The Child Care and Development Fund is managed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that provides assistance to low-income families who need child care during work, work-related training and/or attending school

- Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

- CHIP is administered by states and funded jointly by states and the federal government to provide health coverage to eligible children

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

- EITC is a tax credit program for workers with low to moderate-income levels, managed by the U.S. Department of Treasury

- Head Start Program

- The Head Start program promotes school readiness for children from low-income families from birth to age five and emphasizes the importance of parents as their child’s first teacher

Key Takeaways

- Socioeconomic status (SES) is a measure that includes parental education, marital status, employment, and household income and eligibility for government aid.

- Low socioeconomic status can negatively affect a child’s family well-being, psychological health, physical health, and education.

- Economic stress can hurt relationships between family members, and if a child’s home life is a harmful setting, it can decrease their chances of future success.

- Early childhood exposure to adverse experiences can negatively impact mental health.

- Low SES children display higher rates of physical health issues and long-term chronic diseases.

- Children of lower SES receive less quality education, making it more difficult to pursue job opportunities and escape the cycle of poverty.

- Many government programs are available to help low-income families in areas where they may lack resources, like education, housing, food access, and health insurance.

References

American University. (2020, September 10). Inequality in public school funding: Key issues & solutions for closing the gap. https://soeonline.american.edu/blog/inequality-in-public-school-funding

Benham, B. (2017, November 9). A neighborhood’s quality has a lasting effect on a child’s behavior, study finds. The Hub. https://hub.jhu.edu/2017/11/09/neighborhood-quality-affects-childhood-behaviors/

Chen, E. (2004). Why socioeconomic status affects the health of children. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(3), 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00286.x

Comeau, J., & Boyle, M. H. (2018). Patterns of poverty exposure and children’s trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behaviors. SSM – Population Health, 4, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.11.012

Dowd, J. B., Zajacova, A., & Aiello, A. (2009). Early origins of health disparities: Burden of infection, health, and socioeconomic status in U.S. children. Social Science & Medicine, 68(4), 699–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.010

Escarce, J. (2003). Socioeconomic status and the fates of adolescents. Health Services Research, 38(5), 1229–1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.00173

Friedrich, M. (2021, October 8). Income, poverty and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2019. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/income-poverty.html

Hosokawa, R., & Katsura, T. (2018). Effect of socioeconomic status on behavioral problems from preschool to early elementary school – a Japanese longitudinal study. PLOS ONE, 13(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197961

Jia, X., Zhu, H., Sun, G., Meng, H., & Zhao, Y. (2021). Socioeconomic status and risk-taking behavior among chinese adolescents: The mediating role of psychological capital and self-control. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.760968

Knifton, L., & Inglis, G. (2020). Poverty and mental health: Policy, practice and research implications. BJPsych Bulletin, 44(5), 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.78

Letourneau, N. L., Duffett-Leger, L., Levac, L., Watson, B., & Young-Morris, C. (2011). Socioeconomic status and child development. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 21(3), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426611421007

Männikkö, N., Ruotsalainen, H., Miettunen, J., Marttila-Tornio, K., & Kääriäinen, M. (2020). Parental socioeconomic status, adolescents’ screen time and sports participation through externalizing and internalizing characteristics. Heliyon, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03415

Mathiarasan, S., & Hüls, A. (2021). Impact of environmental injustice on children’s health—interaction between air pollution and socioeconomic status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020795

Singh, G. K., & Ghandour, R. M. (2012). Impact of neighborhood social conditions and household socioeconomic status on behavioral problems among US children. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(1), S158+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A347292713/AONE?u=clemsonu_main&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=9e857732

The Recovery Village Drug and Alcohol Rehab. (2021, November 24). Mental illness and poverty: A depressing reality. https://www.therecoveryvillage.com/mental-health/related/mental-illness-and-poverty/

Adverse Childhood Experiences are traumatic events that occur before the age of eighteen. ACEs include all types of neglect and abuse, such as parental abuse, incarceration, and domestic violence. ACEs also include trauma from a parent who may have fallen ill.

a condition characterized by the excessive accumulation and storage of fat in the body