12 Toxic Stress and Resilience

Sean Graham

Introduction

Toxic stress and resilience are related topics that can powerfully alter the health and wellbeing of children for the entirety of their lives. Toxic stress is defined as maintained exposure to stress-causing experiences (Masten, 2018). These experiences of long-term adversity can include physical or emotional abuse, neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and/or economic hardship. Toxic stress can have dangerous consequences for the children who experience it, including a higher risk of brain damage and death from multiple diseases (Wisconsin Department of Health Services, 2020). However, some children adapt to this stress more successfully than others, and this characteristic is labeled resilience. Resilience connects the direct and indirect interactions between a child and their family members, environment, and other adult figures. These interactions impact a child’s ability to cope and adapt to stressful experiences (Masten, 2018).

Toxic Stress

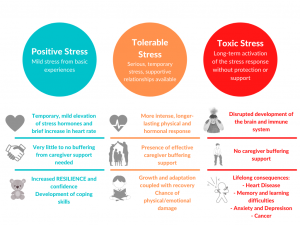

In order to understand the effects of toxic stress, it is essential to distinguish types of stress responses and the role they play in children’s lives. The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University categorizes stress in three ways: positive stress response, tolerable stress response, and toxic stress response (Harvard University, 2020).

Understanding the family and social structure surrounding a child can be a significant source of information regarding possible sources of toxic stress. Additionally, without proper caregiver buffering support, the effects of toxic stress can be much more dangerous. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recognizes risk factors for toxic stress, including social isolation, poverty, low educational achievement, single-parent home, and parent factors such as low self-esteem, substance abuse, and depression (Franke, 2014). The AAP does not have a specific screening tool for toxic stress as of 2022. While not always easy to recognize, some short-term behavioral changes may indicate excessive stress in children’s lives. These changes include mood swings, poorer impulse control, reduced problem-solving confidence, and less overall confidence (Nelson, 2020). By knowing what to look for, all adults in leadership or nurturing positions can provide the best possible care for children at high risk for toxic stress.

Effects of Toxic Stress on the Mind and Body

Toxic stress can impact a child’s body in many ways, including physically and mentally. Toxic stress often alters brain chemistry, brain anatomy, and even gene expression (Phang, 2017). When a child experiences toxic stress, the body overproduces stress hormones (specifically the hormone cortisol), leading to higher blood pressure, increasing inflammation, and decreasing immunity. The brain’s structure can be changed due to these effects, leading to health problems throughout life (Phang, 2017). The consequences of these structural changes include increased anxiety and impaired memory and mood control. Additionally, studies have found that toxic stress-inducing experiences are associated with chronic health conditions, including diabetes, heart disease, and cancer (Phang, 2017).

Resilience

No two children’s toxic stress experiences or responses are the same. Thus, it is essential to recognize how adult figures can best support the development of resilience in children faced with toxic stress. While there is no one formula for developing resilience, researchers have identified multiple factors contributing to childhood resilience. These resilience-promoting factors include close adult-child relationships, problem-solving skills, positive self-image, routines, and engagement with a well-functioning school (Masten, 2018). Furthermore, strategies for promoting resilience should focus on four major factors: promoting supportive adult-child relationships; building a sense of self-efficacy and perceived control; providing opportunities to increase confidence in adapting to new situations; and uplifting sources of faith, hope, and cultural traditions (Harvard University, 2020).

Additionally, timing impacts these resilience-promoting factors. There may be windows of opportunity that are more advantageous than others, such as natural periods of rapid development (Masten, 2018). For example, the preschool years represent a period of rapid development of social, behavioral, and problem-solving skills. The children who most often fall behind in developing these skills come from high-risk backgrounds. In contrast, other time windows may open in direct response to an adverse experience, such as an episode of abuse at home. These windows present the opportunity to recognize the presence of stressful events and surround that child with increased resilience-promoting factors (Masten, 2018).

Resiliency can lead to the increased ability of children to adapt and cope with stressful situations. Additionally, these children often show signs of increased curiosity, bravery, and trust in their instincts (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). These characteristics all aid a child’s ability to succeed academically and socially early in life. By fostering environments that promote resilience and reduce stress, caregivers can provide all children opportunities to persevere and thrive (Gartland, 2019). This support can help bolster children’s ability to succeed academically and socially as well as experience greater health throughout their entire lives.

Resources

Caregivers of all kinds can impact the amount of toxic stress in a child’s life and help cultivate environments that lead to greater growth of resilience. The resources listed below provide additional information on toxic stress and resilience as well as strategies for creating the most supportive environments for all children.

- Harvard University.

- Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child has multiple videos and short articles on toxic stress and how we can combat it in children’s lives.

- Aces Aware.

- Aces Aware provides a quick fact sheet on how to reduce the impact of toxic stress.

- EducationWeek.

- EducationWeek provides simple strategies teachers can use to reduce toxic stress in the classroom.

- American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association supplies parents, caregivers, and teachers with a list of 10 tips for building resilience in children and teens.

Key Takeaways

- All caregivers can help create environments and experiences that reduce toxic stress and increase the development of resilience.

- Toxic stress can alter brain chemistry, brain anatomy, and gene expression.

- There are windows early in a child’s life where the ability to build resilience and be affected by toxic stress is higher (e.g. Preschool years).

- Caregivers should focus on these resilience-promoting factors: close adult-child relationships, problem-solving skills, positive self-image, routines, and engagement with a well-functioning school.

References

Franke, H. (2014). Toxic stress: Effects, prevention and treatment. Children, 1(3), 390–402. https://doi.org/10.3390/children1030390

Gartland, D., Riggs, E., Muyeen, S., Giallo, R., Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H., Herrman, H., Bulford, E., & Brown, S. J. (2019). What factors are associated with resilient outcomes in children exposed to social adversity? A systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024870

Harvard University. (2020, January 6). A guide to toxic stress. Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/guide/a-guide-to-toxic-stress/

Masten, A., & Barnes, A. (2018). Resilience in children: Developmental perspectives. Children, 5(7), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5070098

Nelson, C. A., Bhutta, Z. A., Burke Harris, N., Danese, A., & Samara, M. (2020). Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ, m3048. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3048

Phang, K. (2017, July 13). Toxic stress: How the body’s response can harm a child’s development. Nationwide Children’s Hospital. https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/family-resources-education/700childrens/2017/07/toxic-stress-how-the-bodys-response-can-harm-a-childs-development

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021, November 22). Childhood resilience. https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources/hpr-resources/childhood-resilience

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2020, November 16). Resilient Wisconsin: Trauma and toxic stress. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/resilient/trauma-toxic-stress.htm

adverse or unfavorable fortune or fate; a condition marked by misfortune, calamity, or distress

Decreasing the strain on the body caused by increased stress through positive parenting behaviors.

the process by which possession of a gene leads to the appearance in the phenotype of the corresponding character

The pressure of the blood in the circulatory system, often measured for diagnosis since it is closely related to the force and rate of the heartbeat and the diameter and elasticity of the arterial walls.

Swelling, redness, and a burning sensation of a part of the body.

a condition of being able to resist a particular disease especially through preventing development of a pathogenic microorganism or by counteracting the effects of its products

an individual's belief in his or her ability to complete tasks or behaviors for necessary achievement

A child’s belief that they have control over their inside state