2 The Aeroplane, The Automobile, And The G.I. Generation

David Barnett

2.1 Introduction

Keywords

- G.I. Generation – The generation of Americans defined by service in WWII, born in the early 1900s-1920s.

- Airmindedness – The movement in America and Europe of the early 20th century, characterised by a fascination and excitement with the airplane and air travel.

- Fordism – The philosophy of modern manufacturing, characterized by standardized parts, unskilled workers, and the moving assembly line.

- Moving Assembly Line – A method of manufacturing wherein the work piece is transported from station to station, with workers at each station installing a standardized part or performing a single standardized task on each piece as it comes to them.

Learning Objectives

- By the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Describe the evolution, and mass adoption of the automobile in the early 20th century.

- Describe the invention, evolution, and mass adoption of air travel in the early 20th century.

- Articulate the social impacts of the personal freedom of movement provided by the automobile.

- Articulate the social impacts of early air travel and the “airmindedness” movement.

2.2 The Automobile and Airplane

Key Takeaway

The automobile and the airplane allow us to move freely, allow businesses to transport their goods and services, shape our infrastructure and culture, and bring our world closer together.

2.2.1 Automobile

We’re all familiar with the automobile today. Paved roads and highways crisscross our towns, states, and country. Service stations, mechanics, rest stops, and motels dot the landscape all along these arteries of transport and commerce. For many of us, our daily lives of work, school, and recreation depend on the automobile to get us around. But it wasn’t always this way: the car culture we live in was the result of a revolution in transportation that hit the United States during the early 20th century, just in time to transform the lives of the young G.I. Generation.

2.2.2 Airplane

Similarly, air travel is now woven ubiquitously into our modern world. Airports across the world are bustling ports of travel and commerce, sending goods and travelers around the world in only hours. For those with a few hundred dollars to spare, the furthest corners of the world are only a day away. But again, things weren’t always this way: while the G.I. Generation was coming of age in the 1910s to 1930s, commercial air travel and cargo delivery services were in their infancy. Trans-oceanic flights went from an impossible dream in the teens, to a daring feat of the 1920s, to regular service of mail delivery in the 1930s, to a cornerstone of military strategy in World War II. This evolution continued to their present role as indispensable tools of personal, commercial, and military transport across the world.

2.3 Evolution From the Wright Flyer and Horseless Carriage

Key Takeaway

While the automobile grew from a novelty in the late 19th century to a ubiquitous tool by the 1930s, air travel was invented at the turn of the century and grew up with the G.I. Generation, fully coming of age alongside them in World War II.

2.3.1 Ford And The Modern Car

The evolution of the modern automobile began in late-19th century Europe. Early models, handbuilt by skilled machinists and workmen, were much more similar to the horse-drawn carriage than modern industrially manufactured models. Engines varied from steam, to primitive electric drive, to petrol combustion engines. However, a common issue prevented any of these models from catching on with the masses: due to their specialty coachbuilt nature, they were extremely slow to produce and expensive to purchase. Additionally, it was some time before their performance grew enough to replace the horse carriage (Flink, 1990).

“1908 Ford Model T” by Rmhermen is in the Public Domain.

The genesis of the modern automobile age came in America, brought about by Henry Ford’s assembly line method. By standardizing handcrafted parts, mechanizing manufacturing, and replacing skilled artisans with assembly line laborers, this Fordism model of production revolutionized the automobile industry. The first moving assembly line, now the industry standard for manufacturers, was first tried in Ford’s Highland Park, Michigan plant in 1908. By 1913, it was the standard at Ford Motor Company. Now being produced at low cost and massive scale, the Ford Model T was able to catch on as the first mass market automobile (Flink, 1990). From this point on, decades of continuous refinement in performance and cost efficiency developed the early Model T and its contemporaries into the modern car and truck.

2.3.2 Early Flight

The first heavier-than-air powered flight was performed by Orville Wright at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Ohio bicycle mechanics Orville and Wilbur Wright began working on the problem of heavier-than-air powered flight as early as 1897. After years of testing, progressing from kites, to wind-tunnel models, to gliders, finally the full powered aircraft was ready for testing in late 1903. On December 17th at 10:35AM, the Wright Flyer took off under its own power, beginning the age of aviation. Over the following decades, the utility of the airplane was discovered in multiple roles. In World War I, it replaced the immobile balloon for airborne reconnaissance, and the addition of mounted machine guns made for the first aerial combat (Hallion & Mason, 2010). Much like the automobile, the airplane evolved rapidly in the early decades of the 20th century, greatly increasing in power, reliability, range, and carrying capacity.

“Charles A. Lindbergh, with Spirit of St. Louis in background, May 31, 1927” is in the Public Domain.

1927 saw Charles Lindbergh’s historic flight from New York City to Paris, the first trans-Atlantic flight. This achievement paved the way for the first intercontinental air cargo, mail, and passenger services in the 1930s. Seaplanes were employed to establish the first trans-Pacific mail routes, connecting North America to East Asia by plane for the first time (Freeman). Long distance flight would go on to define the Allied war effort as the G.I. Generation brought the airplane to its full potential. Air supply chains, personnel transport, and long distance bombing raids were all cornerstones of the war effort in both Europe and the Pacific (Hallion & Mason, 2010). Following the war, these uses of air power evolved to meet civilian commercial and personal travel needs as the civilian airlines came to prominence (Corn, 1983).

2.3 The G.I. Generation – Growing Up Mobile

Key Takeaway

While mass adoption of the automobile transformed American culture in the early 1900s by promoting new independence and freedom of movement for the masses, the rise of the airplane and powered flight captured the young G.I. Generation’s imagination and brought the country and world closer together.

2.4.1 Transportation Revolution

The independence and personal freedom brought on by the automobile and airplane extended far beyond simple mobility. It sparked changes in American communities, ways of life, and social roles. Businesses were transformed by the new ability to move goods and people hundreds of miles via automobile, with a new infrastructure of roads and service stations springing up to span the country. Likewise, early efforts in airmail and commercial air travel connected communities across oceans and shortened weeks or months-long journeys to days.

2.4.2 The Promise of Mobility

The automobile and the airplane alike sparked a revolution in business and in the personal lives of Americans. Mobile workers such as delivery drivers, field technicians, and salesmen could greatly expand their range of business with the mobility of an automobile. Similarly, workers able to commute by car could work in the city while moving farther out in the country to live. In this way, the mass adoption of the automobile created the American suburban lifestyle as we know it today (Flink, 1990). This change was also reflected in the sharp decline in urban transit ridership: as workers moved out to the suburbs, cities across America saw a drop in the use of streetcar and tram infrastructure (Young, 2015). The automobile also transformed recreation: families could now easily travel to vacation destinations to enjoy holidays together, or simply go for a drive in the country on a Sunday afternoon.

As the automobile concretely changed the lives of many Americans, the early promise of the airplane captivated their imaginations. Much like the exciting advances in space flight captivate us today, the young G.I. Generation were inspired by pilots such as Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart taking to the skies in daring long distance flights. Reporter Richard Harding Davis captured this fascination after his first time in the air, writing:

This fascination with the power and speed of air travel and the promised technological wonders of the airplane became known as the “airmindedness” movement. This movement continued throughout the 1920s and 1930s until the airplane came fully to prominence, piloted by the G.I. Generation, in World War II (Corn, 1983).

2.4.3 Further Social Ramifications

In addition to freedom of movement for families and expansion of businesses, the automobile made some potentially unintended social changes. Women, whose roles were previously confined mostly to the home, gained their own independence and freedom of movement from the automobile. They didn’t stop there, using this freedom to advance their rights and freedoms. In April 1916, Nell Richardson and Alice Burke embarked on a 10,000 mile cross-country journey in support of women gaining the right to vote. Among the first women to drive such a distance by automobile, they traveled from city to city attending rallies and marches across America in support of womens’ suffrage (The Day Book, 1916). Their journey exemplified the change happening on a smaller scale in homes and communities across the country, as women of the G.I. Generation grew up with new expectations of personal freedom and independence.

“Suffragettes – Mrs. Alice Burke and Nell Richardson in the suffrage automobile “Golden Flyer” in which they will drive from New York to San Francisco. April 7, 1916.” is in the Public Domain.

While unknown to the G.I. Generation at the time, we know today the ecological ramifications of this transportation boom. The age of the automobile and airplane came with a price: an incredible appetite for oil, with all industrial societies the world over coming to rely on it. This appetite has manifested itself in the effects of climate change and global warming today, as well as in the many conflicts fought over oil resources in the decades since mechanization.

2.5 Transportation Culture Through Today

Key Takeaway

2.5.1 America’s Car Culture

Living in America today, we cannot escape the role the automobile has come to take in our lives. Our infrastructure is built around the automobile: roads and parking lots crisscross our towns, highways connect the furthest corners of our countries, even our homes are built with garages to house our family cars and trucks. Outside of major cities, to even get around without a personal automobile is almost unthinkable. Our cars carry us to and from work, to recreation and on vacation. Trucks carry our goods across our highways to stores and businesses. Many of us live in vast suburbs made possible only by each family’s ownership of a personal automobile, or several, to get around. This transformation into an automobile culture began with the G.I Generation.

2.5.2 A Jet Set World

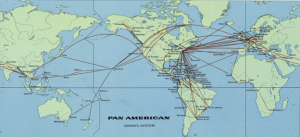

“Pan-American Route Map, 1960s” by adavey is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Likewise, after the G.I Generation cemented air travel’s place in World War II, it has never left our culture. The early efforts of the 1930s in intercontinental passenger and mail service, fully brought to bear in the war, were then expanded to the vast network of jet airlines we know today. Businesses and travelers began using this network of civilian flights in the “jet set” post-war period and their influence continues today.

Case Study: Miss Ella Bartlett of Brookfield, MA

Miss Ella Bartlett grew up in rural Massachusetts before the adoption of the automobile. Read how she describes preparing for a trip to Worcester, a nearby city, by horse drawn buggy:

“When I was a young girl, if we wanted to go to Worcester and were goin’ to drive…we’d begin makin’ plans a week or two in advance. We would make a list of the things we wanted and what our neighbors wanted… It would take at least four hours to reach there for remember the roads were not what they are nowadays. But we wouldn’t be tired, leastways, not us young folks, we’d be too excited. We always took a lunch and every now and then we’d take a sandwich and munch away on it as we went along. We’d shop, as we call it nowadays, it was ‘tradin’’ then, until it began to grow dark and then we’d start for home, more dead than alive, but at that, all kinda quivery inside from the excitement of it all. “We’d get home and be dog tired for a day or two, but, oh, my dear woman, that trip would last us for weeks and weeks and of course, we’d be consulted as to the ‘latest’ styles until someone else made the trip.”

Now consider this: The trip from Brookfield to Worcester is only 20 miles! Many of us today make such a journey, roughly a 30 minutes’ drive by car, just to go to work or school each morning. How different would your life be today if a 20-mile drive was an all day affair, requiring weeks of planning?

Chapter Summary

The automobile and the airplane have come to be cornerstones of American culture, and they grew up right alongside the G.I. Generation in the early 1900s. From the Wright Flyer and the Model T to the ubiquitous American car culture and the worldwide air travel networks of World War II and the jet set eta, these revolutions in transportation have been defining elements of the lives of those born in the G.I. Generation. While these technologies have come with benefits and costs, they are now an inextricable part of our American culture.

Review Questions

Food For Thought

- Reflect on how much of your current culture depends on the automobile and air travel advances brought about with the G.I. Generation. How might your life be different without these technologies?

- As the airplane and automobile transformed the lives of the young G.I. Generation, which upcoming technologies do you think may transform your current generation? Or the lives of the upcoming next generation?

References

Bassett, L. G. & Bartlett, E. (1939) Miss Ella Bartlett. Massachusetts. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/wpalh000624/.

Corn, J. J. (1983). The winged gospel: America’s romance with aviation, 1900-1950. Oxford University Press.

Golden Suffrage Car With Crusaders and Gowns Start 15,000-Mile Tour. (1916, April 12). The Day Book. Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045487/1916-04-12/ed-1/seq-13/#words=nell+richardson+alice+burke+flyer+golden+suffrage+flier.

Flink, J. (1990). The Automobile Age. Retrieved from https://hdl-handle-net.libproxy.clemson.edu/2027/heb01136.0001.001.

Freeman, R. (n.d.). The Pioneering Years: Commercial Aviation 1920 – 1930. Air Transportation: The pioneering years: Commercial aviation 1920-1930. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://www.centennialofflight.net/essay/Commercial_Aviation/1920s/Tran1.html.

Glenshaw, P. (2021, April 1). The airplane changed our idea of the world. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/call-new–180977307/

Hallion, & Mason, R. (2010). Strike From the Sky: The History of Battlefield Air Attack, 1910-1945 The University of Alabama Press.

Young, J. (2015). Infrastructure: Mass transit in 19th- and 20th-century Urban America. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.28