5 Mass Transportation: Chariots & Jets

Kyle Jenko

5.1 Introduction

Keywords

- Automobile – a usually four-wheeled automotive vehicle designed for passenger transportation

- Public Transportation – a system of trains, buses, etc., that is paid for or run by the government

- United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) – the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. Precursor to the United States Air Force

- Demobilization – to discharge from military service

- Suburbs – a district lying immediately outside a city or town, especially a smaller residential community

- The Finletter Commission – a task force (the Air Policy Commission) on the future of U.S. air power. Finletter was the principal author of the commission’s influential 1948 report, “Survival in the Air Age,” which led to the rapid expansion of the U.S. Air Force.

- National Security Act of 1947 – An Act To promote the national security by providing for a Secretary of Defense; for a National Military Establishment; for a Department of the Army, a Department of the Navy, and a Department of the Air Force; and for the coordination of the activities of the National Military Establishment with other departments and agencies of the Government concerned with the national security.

- Berlin Airlift – one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies’ railway, road, and canal access to the sectors of Berlin under Western control.

- Interstate highway system– The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States.

- Jet engine– a type of reaction engine discharging a fast-moving jet that generates thrust by jet propulsion.

- Supersonic flight – flying faster than the speed of sound (767 mph).

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Understand how World War II created a bigger market for the aviation industry

- Explain how civilian restrictions on automobiles contributed to the war effort

- Demonstrate a basic understanding of how cars contributed to suburbanization

- Compare and contrast differences in transportation technology from before the war and after the war

As they grew up, Americans of the Silent Generation witnessed their country cement its status as a world superpower. Participation in World War II and its aftereffects shaped the development of transportation technologies for generations to come. Although invented in a previous era, this generation reaped the benefits of a burgeoning car-centric culture and the genesis of jet powered aviation. The rise of automobile ownership coupled with more powerful aircraft encouraged Americans to travel more frequently and for cheaper. They now felt comfortable moving away from urban population centers and forging their own identities in the suburbs.

5.2 The War Years 1940-1945

Key Takeaways

Japan and the United States have had a tenuous relationship since the mid-19th century, each wary of the other’s territorial expansions. By the 20th century, rising nationalist sentiment encouraged Imperial Japan to expand its borders by invading Indochina. Washington disapproved of such unprovoked aggression by stopping the trade of aircraft and machine tools. Undeterred, Japan continued its conquests with the capture of French Indonesia, which forced America to take more drastic measures by ceasing oil exports in 1941. Negotiations surrounding the trade termination resulted in a diplomatic stalemate. Further frustrated by a lack of cooperation, Japan launched an attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. This “pre-emptive” strike did little more than anger the American people, thrusting them into a conflict even greater than the last.

5.2.1 Driving Sacrifices

By the dawn of the 1940s, America had fully embraced the automobile. Approximately 88% of households owned a car and the number was rising. On September 12, 1941 the Ford Motor Company introduced a fast and heavy, new model that would be the talk of the town. This would be the last group of new cars Americans would see for years. As industry drummed up production for the war, spare automotive parts would become increasingly more scarce. The most precious of which was rubber. (Burns) Japan’s expansion into the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) and British Malaya cut off about 90% of America’s natural rubber supply. The federal government responded by regulating the usage of limited resources and promoting a propaganda campaign to encourage compliance. In June 1942 President Roosevelt created the Office of War Information (OWI); among their objectives included gasoline rationing, reduced speed limits, and the preservation of tires. Excessive or “improper” use was tantamount to treason. (Smithsonian 2019)

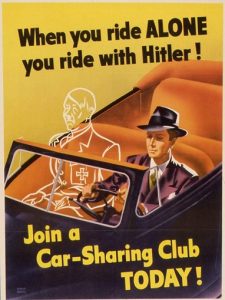

The campaign established the idea that Americans can make contributions to the war effort through “proper” driving and reinforced the notion that automobiles were an integral part of the American lifestyle. Popular depictions showed citizens happily “doing their part” by driving the “Victory Speed”- 35 miles per hour – in order to conserve fuel. A March 1943 press release proclaimed, “The privately owned automobile is no longer the exclusive concern of its owner. The car owner has in fact become the custodian of a vital unit in America’s wartime transportation system”. Driving, an arguably banal activity, was now an act of patriotism. The OWI went so far as exclaiming that those who use public transportation are doing a great “disservice” to their country. (Smithsonian) As a solution, they promoted car sharing with slick ads like Figure 1, emphasizing how drivers can choose who they ride with, as opposed to public transit. Busses and trolleys quickly became a symbol of class and racial divide as driving was portrayed as a “white” activity while riding was not.

“When You Ride Alone You Ride With Hitler” by Gilbert Weimer Pursell is in the Public Domain

5.2.2 Attaining Air Dominance

Prior to the war, commercial flying was an uncomfortable experience. Cabins were cold and noisy and the unpressurized planes were forced to fly at lower altitudes where they experienced the most turbulence. Air sickness was a common occurrence. Despite these details, flying was an expense only businessmen and wealthy fliers could afford. A coast-to-coast round trip cost around $260, about half of the price of a new automobile! Once the United States entered the war, aircraft manufacturers switched production to entirely military applications. (Smithsonian)

Most aircraft were dedicated to the war effort, with a total of over 380,000 manufactured by the war’s end. These planes could be classified as fighters, bombers, and transport. Their technical achievements and sheer numbers displayed the power of American manufacturing. Companies like Boeing, North American Aviation (NAA), and Consolidation Aircraft Corporation (CAC) designed and built key aircraft that helped win the war. NAA’s P-51 Mustang proved to be America’s top fighter platform. Outfitted with a Rolls Royce engine, it could reach top speeds of 450 mph and altitudes of 40,000 ft. While the maneuverability and speed of fighters elicited great respect, the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) showed more favor towards the bomber aircraft. Aircraft like CAC’s B-17 Flying Fortress and B-25 Mitchell and Boeing’s B-29 Superfortress gained their fame through the countless air raids of the war. Key transport planes like Douglas C-47 and the PBY Catalina proved to be invaluable as well. (Bathe & Gibbs-Smith, 1970)

5.3 The Changing Landscape 1946-1950

Key Takeaways

On August 14, 1945 Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allied Forces, marking the official end to the war. Post-war America would experience an economic boom built upon the logistical and political lessons learned during the conflict. Most entered this new era with unbridled optimism and unfettered confidence partially due to military victory and partially due to prospects of upward mobility never before seen in the United States. Their dreams of a peaceful future would soon become clouded by new challenges. By 1948, the Western Bloc would be mired in a geopolitical struggle with the Eastern Bloc, known as ‘The Cold War’.

5.3.1 A Growing Car Culture

Beginning in the 1920’s and further accelerated after the war, many businesses moved out of city centers to the suburbs. ‘The suburban strip’ they built was a bustling place where car owning consumers could shop for all their everyday needs. Having grocery stores, car dealerships, and boutique shops in one commercial strip greatly simplified the shopping experience and soon became the center of American social life. Stores moved from downtown to the outskirts of cities because there was more room to park, unintentionally causing the economic decline of many downtowns. Shopping and driving was now a seamless activity that offered a greater degree of comfort and convenience compared to the busy city centers. (Singer 1979). Americans, particularly The Silent Generation, began expressing their individuality through car customization. ‘Hot Rods’ became a symbol of defiant youth whose loud paint jobs and chrome exteriors Ignored more practical tastes (Lemmon 1979). These cars sold themselves, as demand far exceeded the supply. Consumers wanted new features, fun styles, and low prices, giving manufacturers an easy time promoting the car as a reflection of an owner’s status and self-image. (University of Oxford 1996)

5.3.2 Expanding Airlines

Commercial air travel surged to new heights at the end of the war. New companies emerged and newer aircraft revolutionized civil aviation. The federal government responded by organizing its regulatory agencies to manage the growing industry. On May 13, 1946 President Harry Truman signed the Federal Airport Act, establishing the first peacetime program of financial aid to civil airlines. New airports soon popped up across the country, presenting economic opportunities with easier travel. (FAA) In the same year, manufacturer Douglas developed the DC-6, one of the first postwar airlines that offered a pressurized cabin. Meanwhile, Russian-born American Igor Sikorsky had been developing an aircraft of his own since 1939. In 1946, America adopted his ‘classic’ Sikorsky R-5 helicopter (Figure 2), the world’s first serviceable rotary aircraft. His invention would soon become famous during the Korean War. (Bathe & Gibbs-Smith, 1970)

“Sikorsky XR-5” by National Air and Space Museum, United States Air Force is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

After conflicts ceased, the Army Air Corps began rapid demobilization. The sharp reduction in size led to greater political instability within the branch as they received less funding and had to decommission units. Interest in air superiority would ultimately save the organization. President Harry Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947 that would reorganize the USAAC into its own branch: the United States Air Force. Those who had served were “shaken” by the experience of battling German jet fighters and bombers; veterans would pressure the newly minted USAF to invest in jet research. The entire turbojet engine industry of the United States grew directly from the acquisition of two British engines (The Jet Makers). Five events followed that would transform the aerospace industry. The first would be The Finletter Commission, a five man team that aided Truman in drafting national air policy. This would be followed by the development of air coach and tourist transportation by Capital airlines. Capital’s work quickly spread to its competition where commercial air travel evolved into truly mass transportation. The third event would be the Berlin Airlift, a daring campaign to drop supplies to Western allies in Soviet blockaded Berlin. The following year the Soviets detonated their first nuclear device, scaring US policy makers into supporting aerospace research. The final event was the Korean War. (Bright 2021)

5.4 The World Gets Cold 1950-1960

Key Takeaways

On the other side of the globe, China had been fighting a civil war that would be interrupted by Japan’s invasion. Conflict would continue after Japan surrounded and withdrew from mainland Asia. Growing Communist sentiment encouraged the Chinese Communist Party to crack down on all opposition within the country, mainly the Republic of China. Their ensuing conflict would result in a CCP victory lead by Mao Zedong. Seizing a political opportunity, the CCP supported Communist sympathizers in the Korean peninsula. Fearing the inevitable, the United Nations, and subsequently the United States, would posture themselves in a defense position along the 38th Parallel. The ensuing war would mark the first conflict of the greater ideological struggle known as The Cold War.

5.4.1 Motor Madness

When Japan surrendered in 1945, there were roughly 26 million cars in the United States. By 1960, there were nearly 60 million. The ubiquitous nature of the automobile had given birth to the suburbs, the interstate highway system, and drive-through stores, changing the American landscape forever. (Henger & Henger 2012) The 1950s were marked by a unique car frenzy that has yet to be replicated. There was a pre-existing brand hierarchy with Cadillac and Lincoln at the top, that would soon be thrown into the wind by a styling competition.

After a decade of short supply, the automobile industry skyrocketed to a peak of 7.9 million units sold in 1955. About 90% of these new cars were dominated by the Big Three: Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors. Autos used to be based on necessity, but with an increasingly geographically segmented society, 73% of American households now owned a car. This decade’s demand would reflect demographic changes and economic performance. With a solid financial base due to a stronger economy, people now considered styling to be the most important factor in buying a car. Companies’ redesign had to depend more on ‘artistic values’ to sell their products. It can be said “annual redesign was a Faustian bargain, which committed the industry to a quest for eternal youth”. (University of Oxford 1996)

Increased auto ownership caused growing traffic problems and rapid suburbanization threatened the downtowns of many cities. Often, proposed improvements to transportation infrastructure would drive more people out of the city. New housing developments solidified the identity of the ‘suburb’ in an unprecedented scale. These communities would be noteworthy for their uniformity: populated by young, white families. Different demographics were often unwelcome.

5.4.2 The Jet Age

The Korean War, also known as ‘The Forgotten War’, became the “watershed moment” between old piston driven planes and new jet production. By Spring of 1951, neither the Air Force nor the Navy had contracts for piston aircraft. The Bell X-I rocket-propelled research aircraft (Figure 3), piloted by Major. Charles “Chuck” E. Yeager, broke the sound barrier in 1947 proving that supersonic flight was possible. (Lienhard 2014). By the 1950s, the Air Force was fielding an increasingly faster and more powerful fleet of aircraft driven by the jet engine. Turbojet technology introduced the concept of afterburning- permitted large temporary thrust increases by the spraying of fuel into hot exhaust gasses in the tailpipe- allowing pilots to burn faster and for longer. For rotary aircraft, the Korean War would be their proving grounds. Army helicopter pilots aptly demonstrated the logistical capabilities of their craft through frequent cargo lifts and casualty evacuation. (Bright 2021).

“Bell X-1 Glamorous Glennis” by National Air and Space Museum, Department of the Air Force is in the Public Domain, CC0

Back at home, more people were traveling by air than by train for the first time in American history. Airliners had now replaced ocean liners as the preferred method of crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Jet technology finally made it into civilian production with the introduction of the Boeing 707 and the Douglas DC-8 airliners. The jet engine revolutionized the commercial airlines by offering a more robust framework to build bigger and faster planes. It had even entered the American vernacular, “Jetting” was a highly fashionable and prestigious activity that offered unparalleled luxury in the sky. Of course, it was still only for a privileged class. While the airlines were not legally segregated, airports often were. Throughout the South, inferior airport accommodations discouraged African Americans from flying. Until the Civil Rights movement brought change, air travel remained mostly for the white populace (Smithsonian).

“Boeing 707 Passenger Cabin” by Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Boeing is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Case Study: Chicago Car Brains

Chapter Summary

Existing between the more famous Greatest Generation and the Baby Boomers, the Silent Generation witnessed the evolution of both the automobile and the airplane into great tools of mass transportation. They were among the first to use cars more than any other forms of transit and help build the American suburbia. In tandem, development of the jet engine made flying a more comfortable experience, encouraging more Americans to travel with airlines. Both technologies contributed to the diffusion of American culture abroad; the United States effectively used them as tools of “soft power”. The Silent Generation would be the among the first to grow up in a world where everyone recognized the United States as a global superpower.

Review Questions

- Whose jet engines helped grow the American turbojet industry?

- a. Germany

- b. England

- c. France

- d. Russia

- What was “Victory Speed”?

- a. 25 mph

- b. 30 mph

- c. 35 mph

- d. 40 mph

- Who invented the first serviceable Helicopter?

- a. Leonardo Da Vinci

- b. Henry H. Arnold

- c. Charles Yeager

- d. None of the Above

- In 1946, President Truman signed what act, which established the first peacetime program of financial aid aimed exclusively at promoting development of the nation’s civil airports?

- a. Airport and Airway Development Act

- b. Federal Airport Act

- c. Federal Aviation Act

- d. Fly America Act

Answers:

- b. England

- c. 35 mph

- d. None of the Above

- b. Federal Airport Act

Food For Thought

- If the gas and rubber restrictions of World War II restrictions were to happen today, how would it impact American’s lives? How do you think they would respond?

- Has the formation of American car culture had a positive or negative effect on society? If negative, what would you change and why?

- Military and civil aviation is linked by the aerospace industry. Do you think the increased defense funding of the 20th century has had a positive or negative effect on civilian transport? Why or why not?

References

Bathe, B. W., & Gibbs-Smith, C. H. (1970). Aviation: An historical survey from its origins to the end of World War II. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. This book is a comprehensive survey of the history of aviation from its origins to the end of World War II. It contains both detailed pictures and photographs of notable airplanes and appropriate technical specifications. The author, Gibbs-Smith, was a historian and a “Honorary Companion” of the Royal Aeronautical Society. His work provides amble information on the evolution of flight, particularly through the war years.

Bright, Charles. D. (2021). The Aerospace Industry Since World War II: A Brief History. In Jet makers: The Aerospace Industry from 1945 to 1972 (pp. 11–23). essay, UNIV PR OF KANSAS. Bright’s book covers the evolution of Jet aircraft from 1945 to 1972. The chapter of interest details the economic and social drives behind first jets built from the end of World War II and into the Korean War. Overall, it is a well written book.

Burns, K. (n.d.). War production. PBS. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/the-war/war-production#:~:text=American%20industry%20provided%20almost%20two,world’s%20largest%2C%20doubled%20in%20size. Renowned historian and film maker Ken Burns brings World War II into our homes via “The War”. This seven episode miniseries documents the American experience from Pearl Harbor to V-J Day in astonishing detail. It dwarfs any previous documentary not only in scale, but in scope. Once again, Burns does not disappoint.

Federal Aviation Administration. (n.d.). Timeline of FAA and aerospace history. Timeline of FAA and Aerospace History | Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.faa.gov/about/history/timeline The Federal Aviation Administration is the government’s official oversight committee on all commercial and civilian aviation projects. The FAA’s website features a timeline of the organization and its notable activities. This timeline provided key information on the evolution of civilian airlines.

Henger, B., & Henger, J. (2012). The silent generation: 1925-1945. AuthorHouse. The author’s memoir covers his childhood in western Pennsylvania, his experiences living in the American South, and his retirement in the 2000s, including his observations of the drastic social changes experienced in the United State by members of his generation. It covers many firsthand accounts of how technology shaped his generation’s social values.

Kopecky, K. A., & Suen, R. M. H. (2010). A Qualitative Analysis of Suburbanization and the Diffusion of the Automobile. International Economic Review, 51(4), 1003–1037.

Lemmon, S. M. C. (1979). Transportation in the Twentieth Century—A Historical Memoir. The North Carolina Historical Review, 56(2), 194–201. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23534832?seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents. This article is a personal memoir of how transportation impacted Lemmon’s live in the 20th century. It is a solid first hand account of how new technologies changed social dynamics. It is a well written piece, written in prose.

Lienhard, J. H. (2014). Inventing modern: Growing up with X-rays, skycrapers, and tailfins. Oxford University Press. Lienhard documents how technology in the first half of the 20th Century contributed to the novel concept of “modern”, A flurry of exciting new inventions revolutionized the social fabric of America. As a professor of Engineering and History at the University of Houston, he is well versed in emerging tech and its impacts on society.

Singer, C. (1979). A history of technology. The twentieth century c. 1900 to c. 1950, part 1. Oxford University Press. This book details the technological revolutions of America from 1900 to 1950. Although geared more towards history rather than a social analysis, it provides proper insight into the rapidly changing American landscape.

Smithsonian. (2019, April 15). Suburban Strip. National Museum of American History. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://americanhistory.si.edu/america-on-the-move/suburban-strip

Smithsonian. (n.d.). The Evolution of the Commercial Flying Experience. National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://airandspace.si.edu/explore/stories/evolution-commercial-flying-experience#1927

University of Oxford. (1996). The American Automobile Frenzy of the 1950s (thesis). Oxford. Offer’s thesis covers the economic history of the American Automobile Industry in the 1950s. He provides a comprehensive review of how changing American tastes post War shaped car manufacturing. This paper is a good example of a well-researched report.

a usually four-wheeled automotive vehicle designed for passenger transportation

a system of trains, buses, etc., that is paid for or run by the government

the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. Precursor to the United States Air Force

a district lying immediately outside a city or town, especially a smaller residential community

to discharge from military service

An Act To promote the national security by providing for a Secretary of Defense; for a National Military Establishment; for a Department of the Army, a Department of the Navy, and a Department of the Air Force; and for the coordination of the activities of the National Military Establishment with other departments and agencies of the Government concerned with the national security.

a task force (the Air Policy Commission) on the future of U.S. air power. Finletter was the principal author of the commission’s influential 1948 report, “Survival in the Air Age,” which led to the rapid expansion of the U.S. Air Force.

one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, road, and canal access to the sectors of Berlin under Western control.one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, road, and canal access to the sectors of Berlin under Western control.

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States.

flying faster than the speed of sound (767 mph).