15 Eating Disorders

Molly Wiggins

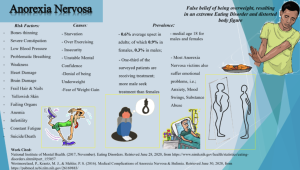

Eating disorders (EDs) are a broad category of behavioral conditions that describe severe disturbances in eating behaviors, distressing thoughts around food, and intense emotions relating to the consumption of food. The three most well-known EDs are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. These EDs are similar because they include severe body dissatisfaction, preoccupation with food, and intense mental distress (Polivy and Herman, 2002). The following definitions highlight the ways they are different. Anorexia nervosa, commonly known as anorexia, is defined by the DSM-V as maintaining a body weight less than 85% of the normal weight for an individual’s age and height (Polivy and Herman, 2002). Classification for bulimia nervosa, commonly known as bulimia, focuses on individuals who practice recurring episodes of binge eating followed by purging to prevent weight gain. Binge eating disorder is classified by periods of uncontrollable eating, or binges. Individuals with binge eating disorder rarely purge themselves.

Diagnosing an individual with an ED is difficult considering many disordered eating habits are practiced in private. Identifying risk factors for the development of these disorders could be helpful in the diagnosis and treatment process for individuals struggling with these health crises. As with many behavioral conditions, the possibility of developing eating disorders depicts the precise controversy of the nature versus nurture debate. Are certain individuals biologically inclined to practice disordered eating habits? Or can specific environmental stimuli invoke these behaviors in any person? The answer comes down to a combination of both influences. Supporting the strength of environmental factors leading to the development of eating disorders, female relatives of individuals with anorexia are 11 times more likely to develop anorexia than individuals without relatives with this disorder. (Bulik et al., 2019). In addition to diagnosed familial members, two of the most pressing external factors for the development of EDs are the media’s idealization of thinness and negative emotionality (Culbert et al., 2015). This includes traits like perfectionism and inhibitory control (Culbert et al., 2015). However, the role of genetics cannot be overlooked. Twin studies show a correlation ranging between 0.46 and 0.79 for the relationship of developing anorexia or bulimia. This highlights the strength genetics may play on developing eating disorders (Bulik et al., 2019). While the role of genetic predispositions for EDs is not well understood, it is important to understand how environmental and sociocultural factors impact the development of EDs. Understanding how environmental factors influence the development of eating disorders is essential to the prevention and treatment of these behavioral conditions.

“Anorexia Nervosa” by David Jr Williams is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Gender Differences in Eating Disorder Prevalence

Most societies believe that only young women struggle with eating disorders. The historically accepted male to female ratio of eating disorder prevalence was 1:10, but recent data shows it is 1:4 (Ammann et al., 2018). This is cause for increased concern, but this data may underreport reality. Males often are reluctant to seek help, or even realize they are practicing disordered eating habits, due to gendered stereotypes and socialization around eating disorders (Ammann et al., 2018). Researchers have identified the “SWAG” stereotype, highlighting the social belief that only skinny, white, and affluent girls are able to have eating disorders (Sonneville and Lipson, 2018). This stereotype leaves higher-weight individuals, racial minorities, individuals from low socioeconomic status homes, older women, and boys and men, without the proper consideration about their potential need for treatment. While women consistently show higher risk and prevalence rates of eating disorders, this issue must not be overlooked in men and boys. Males and females show some similarities in risk factors for developing an ED, like high body dissatisfaction and practicing generalized disordered eating habits (Larson et al., 2021) Still, gender differences underscore the importance of not researching men with EDs through a female prism (Ammann et al., 2018).

Vulnerability During Adolescense

Analyzing the age of disordered eating symptom development is essential to better understand these behavioral conditions. Eating disorders are most frequently developed during adolescence, with most cases showing the onset of symptoms between the ages of 10 and 22 (Ammann et al., 2018). However, the early onset of puberty is theorized to influence the susceptibility of boys and girls differently. Early maturing boys who build muscle mass quickly are seen as more attractive and often have a higher level of body satisfaction. These traits make them less susceptible to developing an ED (Ammann et al., 2018). In contrast, early maturing girls are at an increased risk for developing an ED due to social ostracization from peers. Whereas athletes (of all ages) are slightly more likely to develop an ED, adolescent male athletes are more at risk to exhibit disordered eating behaviors than female athletes of the same age (Ammann et al., 2018). This could in part be due to the accentuated emphasis on body size in male dominated sports like football and wrestling.

Increased Income: Protector or Perpetuator of Eating Disorders?

A key aspect of the previously mentioned “SWAG” stereotype assumes only affluent individuals are most vulnerable to disordered eating. A study published by Cambridge University sought to debunk this myth (Burke et al., 2022). This study was conducted with a sample of 121,000 college students and found that lower socioeconomic status (SES) individuals were 1.27x more likely to practice disordered eating habits than those of higher SES (Burke et al., 2022). Another study took a closer look at binge eating among adults and found a negative association between binge eating and income for women, but no association was found for men (Reagan and Hersch, 2005). Living in a neighborhood with an unhealthy environment significantly increases the likelihood a woman will participate in binge eating (Reagan and Hersch, 2005). This supports the authors’ original claim considering neighborhood environment often positively correlates closely with household income. The authors do not suggest why the frequency of binge eating for men is not influenced by income or neighborhood environment (Reagan and Hersch, 2005). Still, more research is needed to better understand the ways that increased income impacts binge eating differently across gender.

A study from the international journal, Eating Behaviors, shows that for male adolescents and young adults, thinness-oriented dieting, the use of UWCBs (unhealthy weight control behaviors), and the use of EWCBs (extreme weight control behaviors) were more common among the low SES group in comparison to the middle and upper SES groups (Larson et al., 2021). This study found that the largest disparity relating to eating disorders across SES was within the cohort of low SES adolescent boys (Larson et al., 2021). Identifying a male dominated and low-income population in relation to a disordered eating habit further encourages the societal shift away from the “SWAG” stereotype. The evidence from this study further proves the need for continued research on disordered eating habits in young people of both genders across varied socioeconomic backgrounds.

Prevention and Treatment

The most utilized prevention strategy for the development of eating disorders is education-based programs about the dangers of EDs (Bailey et al., 2014). One effective prevention strategy rising in popularity focuses on leveraging cognitive dissonance to target internalized beliefs that may lead to the development of an ED, like the idealization of thinness or fear of gaining weight (Bailey et al., 2014). Current research shows this approach is promising in curbing the development of EDs, however, longitudinal research is necessary to ensure lasting effects are maintained (Bailey et al., 2014). Currently, the most effective treatment for bulimia is cognitive behavioral therapy in combination with the use of antidepressant medications (Bailey et al., 2014). The goal of cognitive behavioral therapy is to instill behavior change by targeting and challenging core beliefs of the patient. Family based therapy is commonly utilized to treat anorexia, albeit with mixed results of success (Bailey et al., 2014). Information about binge eating disorder treatment is widely unavailable. People struggling with binge eating disorder are typically less likely to seek help or diagnose themselves with an eating disorder which could explain this lack of research (Bailey et al., 2014). Treatment strategies are not tailored to meet the needs of populations based on income, gender, or life stage . However, lower income individuals will face more challenges accessing treatment than higher income groups. This is because of the steep barrier imposed by high costs of treatment and lack of insurance coverage for psychological conditions like eating disorders.

An important policy level intervention to increase the accessibility of eating disorder treatment would be mandating insurance plans to cover psychological services to some extent. In addition, requiring Medicaid to cover or subsidize costs for eating disorder treatment would decrease the barrier lower income individuals have to accessing psychological treatment. Addressing eating disorders at the interpersonal level is more complicated. Many eating disorders are fueled by fatphobia under the guise of “promoting health” due to the negative social stigma associated with residing in a larger body (Bombak, 2014). Changing this attitude is essential to reducing the prevalence of eating disorders. Health at Every Size (HAES) is a new health paradigm that strives to shift the narrative away from using weight as an indicator of health (Bombak, 2014). Instead, this ideology promotes eating enjoyable and nutritious foods, practicing intuitive eating, honoring hunger cues, and partaking in physical activity that also nourishes the mind (Bombak, 2014). Most importantly, HAES is actively fighting back against fat stigmas and fat shaming attitudes. Critics fear adopting this paradigm will lead to an overabundant consumption of food and rapid weight gain. While having excess adipose tissue has a mild correlation with poorer cardiometabolic health, sustained restrictive dietary behaviors do as well (Bombak, 2014). Changing the cultural narrative from “thin = healthy” to prioritizing independent health practices not relating to weight loss is an extremely important step at the interpersonal level in stopping eating disorders from developing.

“Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – Basic Tenets” by Urstadt is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Key Takeaways

- High body dissatisfaction is a risk factor for developing an ED in males and females.

- The most effective treatments for eating disorders are cognitive behavioral therapy, family therapy, and the use of antidepressants.

- Health At Every Size (HAES) is an important health paradigm which strives to change the cultural narrative from “thin = healthy” to prioritizing independent health practices not relating to weight loss.

Chapter Review Questions

- What is the most effective treatment for bulimia nervosa?

- A. Family therapy

- B. Hypnosis

- C. Cognitive behavioral therapy

- D. Dieting

- Which is NOT a principle of HAES?

- A. Eating enjoyable and nutritious foods

- B. Counting calories

- C. Practicing intuitive eating

- D. Honoring hunger cues

- Of the following, which is the biggest risk factor for developing an ED?

- A. Being friends with someone who has an ED

- B. Playing a sport

- C. Watching TV

- D. Dieting

- What are two important external factors leading to the development of eating disorders?

- A. The media’s idealization of thinness and negative emotionality

- B. Watching TV and excelling in school

- C. Playing sports and anger management issues

- D. Having a skinny parent and going to college

- What does the “S” in “SWAG” stereotype stand for?

- A. Smart

- B. Skinny

- C. Small

- D. Slender

References

Ammann, S., Berchtold, A., Barrense-Dias, Y., Akre, C., & Surís, J. C. (2018). Disordered Eating: The Young Male Side. Behavioral medicine (Washington, D.C.), 44(4), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2017.1341383

Bailey, A. P., Parker, A. G., Colautti, L. A., Hart, L. M., Liu, P., & Hetrick, S. E. (2014). Mapping the evidence for the prevention and treatment of eating disorders in young people. Journal of eating disorders, 2(1), 1-12. (Bailey et al., 2014)

Bombak A. (2014). Obesity, health at every size, and public health policy. American journal of public health, 104(2), e60–e67. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301486

Bulik, C. M., Blake, L., & Austin, J. (2019). Genetics of eating disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 42(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2018.10.007

Burke, N. L., Hazzard, V. M., Schaefer, L. M., Simone, M., O’Flynn, J. L., & Rodgers, R. F. (2022). Socioeconomic status and eating disorder prevalence: at the intersections of gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity. Psychological medicine, 1–11. Advance online publication.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722001015

Culbert, K. M., Racine, S. E., & Klump, K. L. (2015). Research Review: What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders–a synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(11), 1141-1164.

Larson, N., Loth, K. A., Eisenberg, M. E., Hazzard, V. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2021). Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating are prevalent problems among U.S. young people from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds: Findings from the EAT 2010-2018 study. Eating Behaviors, 42, 101535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101535

Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (2002). Causes of eating disorders. Annual review of psychology, 53(1), 187-213. (Polivy and Herman, 2002)

Reagan, P., & Hersch, J. (2005). Influence of race, gender, and socioeconomic status on binge eating frequency in a population-based sample. The International journal of eating disorders, 38(3), 252–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20177