18 Antisocial Personality Disorder

Robert Capps

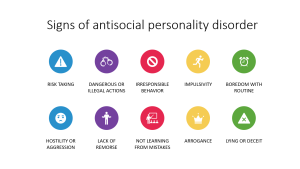

Antisocial personality disorder, or ASPD, is one of the most prevalent mental disorders, especially among men. According to the Cleveland Clinic, the disorder affects between 1-4% of the US population (Cleveland Clinic). However, little is known about the disorder. According to the official Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-V, ASPD is characterized by persons who take part in repeated instances of reckless, troublesome, and criminal behavior (Glenn et al., 2013). One common symptom for the disorder that the DSM-V does not account for is a lack of regret after the incident (Domes et al., 2012). In one study researchers have found that emotional dysregulation is a key describing factor to those that have the disease and causes the onset of violence and deviant behavior in those who have the disorder (Falcus and Johnson, 2018). Emotional dysregulation can be described as an emotional response that is prompted by a stimulus that falls outside of a socially accepted range of behavior. Oftentimes the development of ASPD can be traced back to trauma associated events, substance abuse, and deviant childhood behavior. Those factors are commonly present when studying the development of ASPD. The majority of cases can be followed along a trajectory that starts in early childhood (Howard et al., 2013). That trajectory can be sped up by the presence of substance abuse at any age (Howard et al., 2013). Treatment of the disorder has been researched sparingly over the years. The conclusion among many in the field of psychology is that the issue is not researched enough because the symptoms that characterize the disorder overlap with many other disorders (Glenn et al., 2013). Research that has been conducted shows there are treatment options. Understanding the comorbidity, the presence of another or many other diseases or disorders within an individual, of other psychiatric disorders, such as substance abuse and anxiety with ASPD is key (Glenn et al., 2013). The other disorders act as subtypes to creating helpful treatment options for those with the disorder (Glenn et al., 2013). Due to the variation of the disorder, it has been found that the most effective treatment so far is therapy based discussion that is built on trust and direct resistance of specific risk factors and subtypes of ASPD (van den Bosch et al., 2018). Therapy for ASPD can be a long, slow-moving process, but has been known to be instrumental in the treatment of the disorder.

“Signs of AsPD” by MissLunaRose12 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

ASPD Among Men

One of the common factors that arises when studying the disparity between overall men’s and women’s health is that men are more at risk to partake in risky behavior such as substance abuse, rule breaking, and violence. ASPD among men can contribute to the gap that is found in men’s health. This gap is seen mainly because of traditional masculine behaviors that have been instilled in men from a young age (Galdas et al., 2005). When comparing men and women the prevalence ratio of this specific mental disorder was three-to-one (Alegria et al., 2013). Prevalence is a statistic used to describe the amount of people who have an illness in an area over a specific period of time, therefore a prevalence ratio shows how many people out of the total population have a specific disease or disorder (Alegria et al., 2013). A study of 819 men who have ASPD produced a statistic that approximately 80% of the participants had taken part in an activity at some point in their lives that they would get arrested for and approximately 39% of them physically hurt others on purpose (Alegria et al., 2013).

ASPD and Race

There are a small number of studies that compare ASPD among men of different races. From a study that was conducted on 178 young men, there seemed to be no association between the development of ASPD in men and their race (Dotterer et al., 2019). However, there are certain disparities have been observed in other studies that negatively affect the development of a more intense outcome of ASPD in the individual. For example, a 2019 study of 12,070 participants found that black and latino men were more likely to not use substance abuse treatment services that were provided to them (Pinedo, 2019). The differences between races that are found in categories such as substance abuse, the willingness of a man to receive treatment, trauma exposure, and access to care for the problem can be an underlying determinant of ASPD at the intersection of race. While there is very little significant or specific research that has been done on ASPD regarding race, risk factors such as substance abuse and trauma exposure can be observed that may make men of color more at risk for developing the disorder.

ASPD and Life Stages

ASPD at the intersection of life stages has been studied thoroughly. The life cycle of the disease can be best described as a launching pad that begins in disobedience as a child and develops over time to the onset of ASPD in adulthood (Howard et al., 2013). At different stages of life the risk factors for the development of the diagnosis change (Howard et al., 2013). One of the commonalities that is seen among the duration of the disorder among men in whom the condition begins at an early age is severe conduct disorder (Howard et al., 2013). The disorder turns into substance abuse that later turns into a diagnosis of ASPD (Howard et al., 2013). A recent study on the prevalence of the disorder among a population of older men showed that prevalence hits its peak in early adulthood and drops dramatically as men grow older (Holzer et al., 2022). The researchers believed that the drop in prevalence could be due to older men having a higher chance of being diagnosed with substance abuse or depression instead of ASPD, there was no conclusive evidence if that was true or not (Holzer et al. 2022).

Much to be Done

There is a lack of research done on ASPD among men and the population as a whole. Few are aware that the diagnosis is a looming global problem among men (van den Bosch et al., 2018). There is one major problem that researchers run into when attempting to study the condition. The problem is that the condition is difficult to measure. ASPD is made up of many different subtypes, such as substance abuse, extreme violence, and development of other psychological disorders like bipolar disorder, and the amount of comorbid factors make each case unique (Glenn et al., 2013). The makeup of the diagnosis creates a difficult situation for researchers due to the fact that there can be little valid generalization of the condition across populations. One of the more concerning aspects of the lack of research is that there are that there is little to no resources on how to treat the condition. Due to the ambiguity of ASPD treatment is divided into the parts that make up the condition as a whole such as substance abuse, criminal behavior, or violence. As a result, care providers are only treating a piece of a larger problem (Glenn et al., 2013).

How can we respond?

Due to the lack of research of this specific disorder, there is not substantial efforts being directed towards ASPD in order to treat it (van den Bosch et al., 2018). With that being said, there have been a few attempts to try and treat ASPD According to one study that was testing psychological interventions for ASPD there were only three approaches that were statistically more effective than a control intervention (Gibbon et al., 2020). Those interventions were contingency maintenance alongside standard maintenance, schema therapy, and dialectical behavior therapy (Gibbon et al., 2020). However, those studies also showed that there was no real change in behavior for the patient (Gibbon et al., 2020). It is apparent that some form of psychosocial therapy that is focused on discussion is needed. Psychosocial therapy is a form of therapy that observes the interaction between a person’s social behavior and the thoughts and emotions that they have mentally. This may come in the form of an already established treatment such as cognitive behavior therapy, but the lack of success that has come in treating the disorder points to a new method being needed for treatment. At the policy level education is needed. It is known that the disorder can develop in early adolescence, therefore education should be put into place as early as junior high, if not earlier. It could be as simple as introducing a new unit to biology classes that focuses on human health, specifically at the mental level. More education about the facts and treatment available for mental disorders would help to reduce the stigma behind mental health, especially in men. Most men might not even have the knowledge to know that they have a disorder, they may associate the disorder with an angry or irritable personality that can’t be changed. At the interpersonal level, a strong support system among family members and close friends could be crucial to prevent the onset of ASPD. The launching pad for the disorder often occurs at childhood in the form of repeated simple disobedience with parents and teachers. If parents and teachers have knowledge that this behavior could point towards a future development of ASPD they may be able to change the trajectory of the disorder by supporting the child and helping to change behavior early. The starting point in terms of doing something about the disorder is to conduct more research that could lead to new forms of effective treatment (Holzer et al., 2017).

Key Takeaways

- Men are more at risk to participate in illegal, violent, and risky activities and are more at risk of developing ASPD.

- Describing factors of ASPD begin in childhood and eventually develop into the actual disorder in adulthood.

- ASPD is hard to measure because the parts of the disease, such as substance abuse, violence, and criminal behavior have not all been studied together.

Chapter Review Questions

- How prevalent is antisocial personality disorder in the US population?

- A. 6-10%

- B. 1-4%

- C. 0.1-0.4%

- D. 2-5%

- What is one direct symptom of ASPD?

- A. Rule breaking

- B. General anxiety

- C. Hallucination

- D. Dual personality

- At what life stage does ASPD hit its “peak”?

- A. Early adolescence

- B. Older age (80-90 years old)

- C. Early adulthood

- D. Late adulthood

- What is an underlying determinant of the interaction between ASPD and race?

- A. Substance abuse

- B. Trauma exposure

- C. Access to care

- D. All of the above

References

Alegria, A. A., Blanco, C., Petry, N. M., Skodol, A. E., Liu, S., Grant, B., & Hasin, D. (2013). Sex differences in antisocial personality disorder: Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Personality Disorders, 4(3), 214-222. doi:10.1037/a0031681

Antisocial personality disorder: Causes, symptoms & treatment. Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9657-antisocial-personality-disorder#:~:text=Research%20suggests%20that%20ASPD%20affects,of%20people%20in%20the%20U.S.

Domes, G., Mense, J., Vohs, K., & Habermeyer, E. (2012). Offenders with antisocial personality disorder show attentional bias for violence-related stimuli. Psychiatry Research, 209(1), 78-84. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.005

Dotterer HL, Waller R, Shaw DS, Plass J, Brang D, Forbes EE, Hyde LW. Antisocial behavior with callous-unemotional traits is associated with widespread disruptions to white matter structural connectivity among low-income, urban males. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;23:101836. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101836

Falcus, C., & Johnson, D. (2018). The violent accounts of men diagnosed with comorbid antisocial and borderline personality disorders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(9), 2817-2830. doi:10.1177/0306624X17735254

Galdas, P. M., Cheater, F., & Marshall, P. (2005). Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(6), 616-623. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x

Gibbon, S., Gibbon, S., Khalifa, N. R., Cheung, N. H., Völlm, B. A., & McCarthy, L. (2020). Psychological interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(9), CD007668. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007668.pub3

Glenn, A. L., Johnson, A. K., & Raine, A. (2013). Antisocial personality disorder: A current review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(12), 427. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0427-7

Holzer, K. J., Vaughn, M. G., Loux, T. M., Mancini, M. A., Fearn, N. E., & Wallace, C. L. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of antisocial personality disorder in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 26(1), 169-178. doi:10.1080/13607863.2020.1839867

Howard, R., McCarthy, L., Huband, N., & Duggan, C. (2013). Re-offending in forensic patients released from secure care: The role of antisocial/borderline personality disorder co-morbidity, substance dependence and severe childhood conduct disorder. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 23(3), 191-202. doi:10.1002/cbm.1852

Pinedo, M. (2019). A current re-examination of racial/ethnic disparities in the use of substance abuse treatment: Do disparities persist? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 202, 162-167. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.017

van den Bosch, L. M. C., Rijckmans, M. J. N., Decoene, S., & Chapman, A. L. (2018). Treatment of antisocial personality disorder: Development of a practice focused framework. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 58, 72-78. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.03.002