6 Access to Primary Care

Mac Martin

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines primary health care as “the first level of contact for the population with the healthcare system.” Its goal is to address community health by providing “preventative, curative and rehabilitative services” (OECD, n.d.). In the United States, this care typically takes the form of a physician who serves as the guardian of a patient’s health. Primary care physicians are meant to serve as the point of first contact for patients in the healthcare setting. This allows for adverse health outcomes to be either prevented or managed by the primary care physician as they facilitate their patient’s transfer to more specialized practitioners and orchestrate their patient’s wholistic treatment. There exists a robust body of literature demonstrating the connection between positive health outcomes and primary care access. One study proposed that the correlation stemmed from six mechanisms of primary care

“(1) greater access to needed services, (2) better quality of care, (3) a greater focus on prevention, (4) early management of health problems, (5) the cumulative effect of the main primary care delivery characteristics, and (6) the role of primary care in reducing unnecessary and potentially harmful specialist care” (Starfield et al., 2005).

In light of this, determining the extent of primary care use among Americans is of vital importance. One study found that roughly 75% of Americans reported having a primary care doctor in 2015 which was a decline of 2% from 2002 (Levine et al., 2019). While seemingly insignificant, this two percent reduction is indicative of millions who do not receive vital primary care on a yearly basis. Additionally, a separate review of data produced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 25% of American men reported having no primary care doctor in 2020 (KFF, 2021). Due to the services that primary care physicians provide and the high percentage of individuals with no primary care physicians, it is essential that the barriers to accessing primary care and the determinants informing these barriers be identified and addressed.

In 2018, an international study examined the factors associated with barriers to access to primary care in 11 countries including the United States (Corscadden et al., 2018). The study found that 38% of Americans had experienced several barriers to care before they had connected with a primary care practice. Of particular note were the vulnerable groups that predicted increased difficulty to access to primary care. Individuals with below average income were found to have experienced multiple barriers to reaching a primary care provider in every country studied. A majority of the countries including the United States displayed being born outside of the country as being indicative of encountering barriers to receiving primary care after having established contact with a primary care provider. A similar study found that comparable barriers exist for men in the United States compared to western countries (Gunja, Gumas, and Williams, 2022). The study showed that American men were second to last in reporting a regular doctor when they also reported income related stress as well as that American men were the most likely to forgo or delay care due to cost. Perhaps Even worse, American men were in the top three countries for rate of men going to the emergency department for treatment rather than a regular doctor because they didn’t have one. Given that immigrant status and socioeconomic status are both predictors of difficulty in accessing primary care, this chapter will analyze the intersection between those two populations in men.

“Health Insurance Coverage by Characteristics: 2018 and 2020” by United States Census Bureau is in the Public Domain

What are the barriers to receiving primary care for immigrant populations?

Much of the literature focusing on immigration populations is not confined to the United States. While this may seem unhelpful at first glance, comparing what data does exist for immigrant populations in the United States to that of other peer countriesThis can be helpful for illuminating the unique barriers for access to primary care among immigrant men both within and outside the United States health care system. One such study examined access to care in the United States and Canada. The study found that Americans were as much as one third less likely to have a regular doctor than Canadians. Furthermore, the study showed that disparities based on income and immigration status existed for both countries but were more pronounced in America (Lasser, Himmelstein, and Woolhandler, 2006). The authors went on to surmise that Canada’s universal healthcare system was the main factor informing the difference in outcomes. Under a universal healthcare system, the government pays all healthcare expenses leading to very little cost, if any, to the patient. The United States utilizes a mesh of private and governmental avenues to provide healthcare. Having compared the two countries, it is important to consider whether or not the disparities due to income and immigrant status are the same in Canada as those in the United States. One literature review sought to analyze the barriers experienced by immigrant populations in Canada. The review found that the most significant categories of barriers analyzed were those related to communicative and cultural barriers as well as socioeconomic status despite Canada’s universal system (Ahmed et al., 2016). The review concluded that this barrier was present due to restricted work opportunities leading to the need for low-income immigrants to work multiple low-paying jobs thus prioritizing their healthcare less in the process because they cannot or will not seek it. Finally, the authors cited the need for increased research into male immigrant populations due to a clear research gap being present despite Canadian immigrants being largely male. Having identified barriers to primary care for Canadian Immigrant groups, the focus now turns to analyzing the continuity of these barriers in America.

One of the industries with the largest number of immigrant workers in the United States continues to be the agricultural sector. One study found that 63% of farmworkers in the Eastern United States and 76% of farmworkers in United States as a whole were foreign born. The immigration status of these individuals ranged from full time legal citizen, temporary legal resident, and undocumented illegal residents. Additionally, 81% of farmworkers in the Eastern United States were male compared to the national average of 75%. (Arcury et al., 2018). Because of the varying immigrant statuses present in the sector as well as its male dominated nature, studying factors associated with primary care access within this population is critical. A study conducted by McCoy, Williams, Atkinson, and Rubens in 2017 sought to identify the characteristics of migrant farmworkers reporting a relationship with a primary care physician. Among other characteristics, the study found that sex, length of time in the area of study, and country of birth were predictors in disparities for having a primary care doctor. mMale participants, those born outside the US, and participants who had spent less time in the area were less likely to have a relationship with a primary care physician. The study did note as a limitation the fact that it did not inquire into the immigration status of those born outside of the United States. This is significant because immigration status has been shown to have an impact on insurance status which in turn affects access to primary care.

While studying large immigrant populations such as those in agricultural setting is of importance, a wholistic review of immigrant populations in the US requires studying smaller subsets of the immigrant population. A paper written in 2014 sought to analyzed the barriers to access that were faced by Black immigrants migrating to the United States (Wafula & Snipes, 2014). After reviewing the relevant literature, the paperIt synthesized the main factors informing the barriers to Black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean to receiving health care. The paper found that low literacy among immigrants regarding how the United States health care system functioned, lack of insurance, language barriers, and stigma related to HIV/AIDS all contributed to difficulty in accessing primary care. While pragmatic concerns, such as lack of insurance or a language barrier, were predictors for lack of access to care just as they were for Latino immigrant farmworkers, this paper highlighted the extent that subjective concerns related to stigma and real or perceived lack of understanding contribute to difficulty in accessing primary care among immigrants.

How Does Socioeconomic Status affect access to primary care?

A study analyzing rates of health care use among US born and foreign-born Asians determined that there was a direct correlation between socioeconomic status and use of health care services. Specifically, lower socioeconomic status was a predictor for not having a consistent source of medical care or regular consultation with a physician. (Ye et al., 2012). Socioeconomic factors have played a role in determining poor access to care in each of the preceding immigrant populations. Accordingly, the analysis of how socioeconomic status impacts access to primary care is necessary to fully understand the intersection of SES and immigration status. A study was released in 2021 demonstrating how socioeconomic status impacted both quality and accessibility of healthcare services (Caballo et al., n.d.). Of particular note, were the findings on access to care. Participants of the study from low socioeconomic status were found to generally have lower rates of access to health care services than their wealthier counterparts. It was concluded that high costs and difficulty in finding transportation were the most significant barriers experienced by those of low socioeconomic status when accessing primary care. According to a study conducted by Williams on the health of men SES has a more acute effect on men’s health than it does women’s. Men of every tier of SES were found to have worse health than their female counter parts, but men in the lowest rungs of SES were found to exhibit markedly worse health outcomes than similarly disadvantaged women. Immigration status and SES then have an amplifying effect on one another in terms of accessing primary care particularly in men due to the exacerbated effects of SES on men’s access to care. (Williams, 2003).

One of the primary barriers that people of low socioeconomic status face when attempting to access primary care is a lack of health insurance. To combat this, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010 which sought to expand health insurance coverage by expanding Medicaid eligibility. Following its passage, several studies have been conducted to assess the bill’s impact. One of these studies analyzed how coverage affects low and moderate income men (Cha & Brindis, 2020). The study found that early Medicaid expansion significantly reduced uninsurance among adults with particular effectiveness among young men. Policies targeting very low income individuals were found to have slashed rates of uninsurance by as much as 25%. Medicaid expansion has also had an impact on the coverage of men of a higher socioeconomic status. After the passage of the ACA, some were concerned that the law’s financial penalties under the individual mandate would be more bearable than the higher premiums young, affluent men would face thus driving them away from insurance. The individual mandate was a policy of the law that fined individuals who were not insured thus encouraging them to purchase a health plan from the private plans offered under the umbrella of the ACA. Frequenlty, young men would face higher premiums under te private plans as young men are more lijely to be healthy than older men. Therefore, it might be more financial intelligent for a well to do young man to bear the fine of being uninsured rather than pay high premiums for a plan they may not need. A study conducted by the Ccommonwealth Ffund dispelled the concern that young, high SES men would be driven away from health insurance and showed that the percentage of young, high income men without health insurance fell in states which hadthat implemented the new ACA regulations the percentage of young, high income men without health insurance fell (Glied & Chakraborti, 2018). The authors estimate that the new financial penalties for not being insured as well as the significance of coverage these penalties generated in conjunction with marketing efforts helped to lower the rate of young, uninsured, wealthy men.

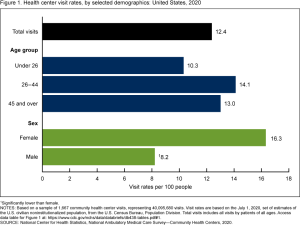

“Health center visit rates, by selected demographics: United States” by CDC is in the Public Domain

Possible Interventions

Much of the literature cited in this study discusses the impact policy would have on access to primary care among the populations of interest. Lasser and Woolhandler (2006) make note of how a universal healthcare system would go to great lengths for reducing barriers for both immigrants and those of low socioeconomic status in the United States. Similarly, virtually every study discussing immigration has called for policy change on that front to mitigate barriers to receiving primary care. The two most direct changes that would benefit both populations would be to increase physical access to primary care and to address high costs. Increasing physical access could come in the form of more transportation services for getting immigrant and low SES populations to primary care centers or alternatively increasing the prevalence of mobile primary care centers that could cater to underserved areas. As for addressing high costs, increased subsidization of healthcare for lower income individuals would go to great lengths in increasing access to primary care in lieu of a full-fledged universal healthcare system. Policy changes are also frequently used to attempt to address issues spefic to immigrant access to primary care. However, these policy changes can sometimes backfire and have more negative results. A 2017 study conducted in a Massachusetts hospital found that those who receive care in another language were more likely to miss an appointment than were those who received care in English following immigration policy changes. (Jirmanus et al., 2022). While policy changes would do much on the socioeconomic front and would have positive impacts for immigrants, it is important to remember that many of the barriers present for those with some level of immigrant status are cultural and interpersonal. In their article discussing health care access among Black immigrants, Wafula and Snipes (2013) write that they could not overstate the importance of cultural competency in ameliorating barriers to access among their population. Simple steps such as offering care in separate languages or providing educational materials would go a long way in helping immigrants feel more comfortable navigating primary care. Primary care doctors can also strive to negate any biases they might posses against those who might come from a different background and work towards being more receptive to those who indicate they would have difficulty accessing primary care due to lack of knowledge or contrasting culture. This could take the form of learning more about the culture of the respective patient populations and perhaps what the male attitude towards seeking care is in those immigration groups. This would allow primary care doctors to become more comfortable relating to their patients while also identifying specific cultural barriers amongst male immigrant sub-groups.

Key Takeaways

- Primary care is intended to be the first point of contact between the general population and the health world.

- The intersection between socioeconomic status and immigration status exists in part because of limited economic opportunities for immigrants which in turn leads to lower socioeconomic status.

- The largest single barriers for immigrant groups to accessing primary care tend to be linguistic, cultural, and knowledge based in nature.

Chapter Review Questions

- One study cited in this chapter mentions six mechanisms performed by primary care that can lead to better health outcomes. Which of the following is one of those functions?

- A. Vaccinations

- B. emotional therapy

- C. life coaching

- D. early management of health problems

- What percentage of American men reported having no primary care physician in 2020?

- A. 12%

- B. 25%

- C. 2%

- D.45%

- The American and Canadian Healthcare systems were contrasted in this chapter because America has a blend of private and public health care whereas Canada has what type of healthcare system?

- A. limitless

- B. global

- C. universal

- D. regional

- The Affordable Care Act sought to increase coverage by expanding what program?

- A. Social Security

- B. Medicare

- C. Medicaid

- D. Welfare Pensions

References

Ahmed, S., Shommu, N. S., Rumana, N., Barron, G. R. S., Wicklum, S., & Turin, T. C. (2016). Barriers to Access of Primary Healthcare by Immigrant Populations in Canada: A Literature Review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18(6), 1522-1540. 10.1007/s10903-015-0276-z

Arcury, T. A., Grzywacz, J. G., Sidebottom, J., & Wiggins, M. F. (2013). Overview of immigrant worker occupational health and safety for the agriculture, forestry, and fishing (AgFF) sector in the southeastern United States. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 56(8), 911-924. 10.1002/ajim.22173

Caballo, B., Dey, S., Prabhu, P., Seal, B., & Chu, P. (n.d.). The effects of socioeconomic status on the quality and accessibility of … Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/isl/files/the_effects_of_socioeconomic_status_on_the_quality_and_accessibility_of_healthcare_services.pdf

Cha, P., & Brindis, C. D. (2020). Early Affordable Care Act Medicaid: Coverage Effects for Low- and Moderate-Income Young Adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 425-431. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.029

Corscadden, L., Levesque, J. F., Lewis, V., Strumpf, E., Breton, M., & Russell, G. (2018). Factors associated with multiple barriers to access to primary care: an international analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 28. 10.1186/s12939-018-0740-1

Glied, S., & Chakraborti, O. (2018). How the Affordable Care Act Has Affected Health Coverage for Young Men with Higher Incomes. Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund), 2018, 1-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29992801

Gunja, M. Z., Gumas, E., & Williams II, R. D. (2022). Are Financial Barriers Affecting the Health Care Habits of American Men?: A Comparison of Health Care Use, Affordability, and Outcomes Among Men in the U.S. and Other High-Income Countries. Commonwealth Fund. 10.26099/d5an-1g87

Jirmanus, L. Z., Ranker, L., Touw, S., Mahmood, R., Kimball, S. L., Hanchate, A., & Lasser, K. E. (2022). Impact of United States 2017 Immigration Policy changes on missed appointments at two Massachusetts Safety-Net Hospitals. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 24(4), 807-818. 10.1007/s10903-022-01341-9

Lasser, K. E., Himmelstein, D. U., & Woolhandler, S. (2006). Access to Care, Health Status, and Health Disparities in the United States and Canada: Results of a Cross-National Population-Based Survey. American Journal of Public Health (1971), 96(7), 1300-1307. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402

Levine, D. M., Linder, J. A., & Landon, B. E. (2019). Characteristics of Americans With Primary Care and Changes Over Time, 2002-2015. Archives of Internal Medicine (1960), 180(3), 463-466. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6282

McCoy, H. V., Williams, M. L., Atkinson, J. S., & Rubens, M. (2016). Structural Characteristics of Migrant Farmworkers Reporting a Relationship with a Primary Care Physician. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18(3), 710-714. 10.1007/s10903-015-0265-2

Men who report having no personal doctor/health care provider by race/ethnicity. KFF. (2021, November 2). Retrieved October 7, 2022, from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/state-indicator/men-who-report-having-no-personal-doctorhealth-care-provider-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22%3A%22Location%22%2C%22sort%22%3A%22asc%22%7D

Primary care. OECD. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/primary-care.htm

STARFIELD, B., SHI, L., & MACINKO, J. (2005). Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(3), 457-502. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

Wafula, E. G., & Snipes, S. A. (2013). Barriers to Health Care Access Faced by Black Immigrants in the US: Theoretical Considerations and Recommendations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(4), 689-698. 10.1007/s10903-013-9898-1

Williams, D. R. (2003). The Health of Men: Structured Inequalities and Opportunities. American Journal of Public Health (1971),93(5), 724-731. 10.2105/AJPH.93.5.724

Ye, J., Mack, D., Fry-Johnson, Y., & Parker, K. (2011). Health Care Access and Utilization Among US-Born and Foreign-Born Asian Americans. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14(5), 731-737. 10.1007/s10903-011-9543-9