2 Lung Cancer

Anna George

While cancer is the second leading cause of death, lung cancer is responsible for most cancer deaths. Lung cancer occurs when mutations disrupt the normal cell cycle and cause abnormal cells to grow uncontrollably (Cancer Treatment Centers of America, 2022). When lung cancer is present, it begins in the lobes and may spread to the bronchi, alveoli, and trachea. The lungs are responsible for the inhalation of oxygen and the exhalation of carbon dioxide (Mayo Clinic, 2020). When the air enters the body, it travels to the lungs from the trachea, into the bronchi, and finishes in the alveoli. The alveoli are tiny air sacs that are responsible for the exchange of oxygen into the blood stream and carbon dioxide out of the bloodstream (American Lung Association, 2020).

Risk Factors and Treatment

The most prevalent risk factor associated with lung cancer is cigarette smoking. Compared to those who do not smoke, cigarette smokers are between 15 and 30 times more likely to be diagnosed and die from lung cancer. Additionally, cigarette smoking is directly related to about 80-90% of lung cancer deaths. Secondhand smoke is also a major risk factor due to the inhalation of the carcinogenic smoke. According to the Centers for Disease Control (2020), “In the United States, one out of four people who don’t smoke, including 14 million children, were exposed to secondhand smoke during 2013 and 2014”. Other risks for lung cancer include exposure to occupational hazards including radon, asbestos, and arsenic (CDC, 2020). All the risk factors stated should be avoided to decrease the likelihood of being diagnosed with lung cancer.

The prevention strategies associated with lung cancer are simply to avoid smoking or stop if you are currently smoking. Additionally, it is important to avoid encountering the previous occupational hazards that were mentioned. When treating lung cancer, the treatment is dependent on the type of cancer, current stage, and patient history. The stages of cancer are broken up into four groups. Stage I is classified as early-stage cancer that has not spread to the lymph nodes or other parts of the body. Stage II and III are classified as cancers that have begun to spread to nearby tissue and may have also spread to the lymph nodes. Stage IV cancer is classified as cancer that has spread to other organs in the body and is the most severe (Collins et al., 2007). This cancer is most commonly treated by surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

“Depiction of a person smoking and stages of Lung Cancer” by Myupchar is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Although most lung cancers only begin to show symptoms once they have spread, some people experience early symptoms that are indicative of lung cancer. The most common symptoms include coughing up blood or dark spit/phlegm, chest pain, loss of appetite or unexplained weight loss, wheezing, shortness of breath, and infections like bronchitis and pneumonia that don’t go away or keep coming back. If the lung cancer has spread to other parts of the body, symptoms including bone pain, headache, weakness or numbness of limbs, yellowing of the skin and eyes, or swelling of the lymph nodes might be present (American Cancer Society, 2019).

Cancer in Men

Racial Differences

The longer someone has smoked, the greater chance for them to develop lung cancer. Generally, men smoke more than women. This is consistent across all racial and ethnic populations besides American Indians where women tend to smoke more than men (American Lung Association, n.d.). The odds that a man will develop lung cancer in his lifetime is about 1 in 15 whereas the odds a woman will develop lung cancer in her lifetime is about 1 in 17 (American Cancer Society, 2022). However, another factor impacts the diagnosis of lung cancer between men and women. When experiencing symptoms, females are more likely to consult with their physician more frequently and with less serious complaints. Women are more likely to schedule an appointment strictly based on symptoms associated with lung cancer. Men usually only report their symptoms in routine consultations, such as their yearly checkups (MacLean et al., 2017). The stigma of seeking help not being seen as masculine causes men to delay seeing their physician, even when dealing with serious symptoms associated with lung cancer. This is a large risk factor for men because it prevents physicians from diagnosing them at an earlier stage.

Overall, African American men are most likely to develop lung cancer compared to other races (Ryan, 2018). As black men are diagnosed at more advanced stages (stages III and IV), their lung cancer mortality rate is 1.35 times higher than white men’s (Sosa et al., 2021). One of the disparities that contribute to African American men having a higher incidence rate is the fact that they are more likely to live in poverty, giving them less access to care and surgical interventions (Ryan, 2018). Living in poverty decreases your chance of having good health insurance because of its high cost. Uninsured adults are less likely to receive preventive and screening services (Institute of Medicine, 2002). Insurance status also varies the rate of lung cancer patient survival. Patients with private health insurance tend to receive more surgical treatment which increases their chance for survival (Ryan, 2018). Additionally, retailers in minority and low-income communities tend to advertise inexpensive and risky alternative tobacco products (Columbia University, 2018). Since people tend to use smoking as a coping mechanism for stress and other issues, it is obvious that advertisers are targeting this population due to their likely high levels of stress.

Hispanic men have the lowest incidence rate of developing lung cancer (Ryan, 2018). This disparity is due to lower smoking rates compared to non-Hispanic Whites. However, many problems are still faced including low socioeconomic status, lower quality of care, and lack of a regular care provider. The survival rate of Hispanic men ultimately shows an advantage over other ethnicities (Price et al., 2021).

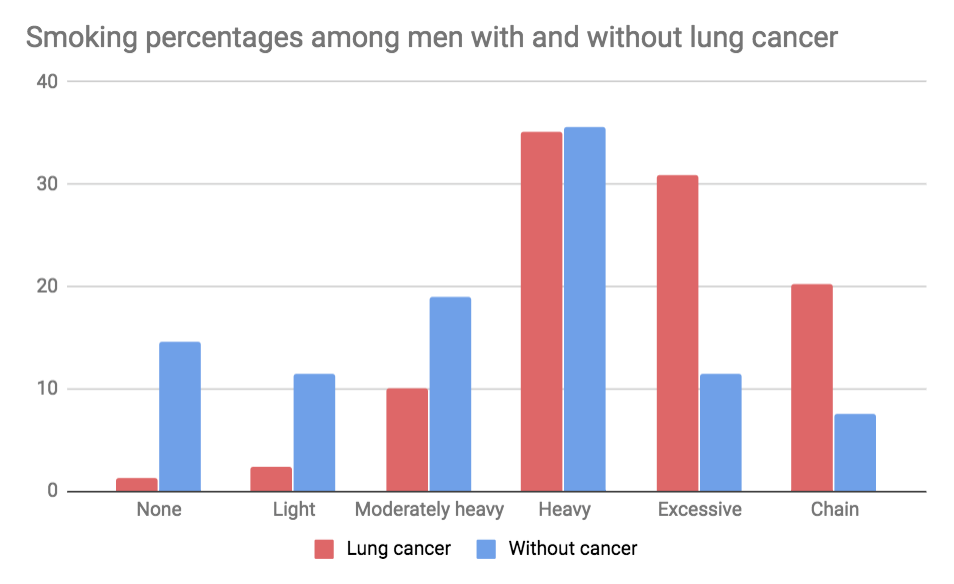

“Wynder and Graham Figure 3” by Littleskimonkey is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Age Differences

Among young adults aged 18 to 35, the lung cancer incidence rate is very low at 1.37%. The survival rate of lung cancer is very high in young adults. Liu et al. (2019) states, “The 1-year overall survival rate was 62.31% and the 3- and 5- year survival rates were both 53.31%”. In this study it was also concluded that the overall lung cancer survival rates of women were superior to men at young ages, however the reason is unknown.

Additionally, when lung cancer is diagnosed in individuals younger than 55, the lung cancer is more likely to be at an advanced stage (Ryan, 2018). This statistic is most likely due to the lung cancer screening criteria which commonly requires that you are between 50 and 80 years of age. This decreases the ability for younger patients to be screened, even if showing symptoms, ultimately giving them the likelihood of being diagnosed with an advanced stage of lung cancer (Ryan, 2018).

Another difference that is seen between younger and elderly patients is treatment. Young patients usually have few physical morbidities, making it possible for them to endure many aggressive treatments that may include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy (Liu et al., 2019). In older patients, treatment is focused on improving quality of life, prolonging overall survival of the patient, and maintaining functional status. After going through 2-3 months of radiotherapy, functional decline of instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) began to increase (Decoster et al., 2017). IADLs include activities such as cooking, cleaning, and transportation. Evidence suggests 8% of young adults are denied surgery compared to the 30% of elderly patients (Venuta et al., 2016).

Interventions

To decrease the rates of lung cancer, it is important to eliminate as many risk factors as possible. Reducing smoking rates, exposure to radon or asbestos, and avoiding secondhand smoke are all achievable factors that could drastically decrease these rates.

Both state and local communities have the ability to play an important role in helping people lower their risk of lung cancer. Reducing minors’ access to both tobacco products and e-cigarettes can target the younger population and attempt to decrease the smoking rates of people under 21 years of age. Since tobacco is an addictive substance, it is important to reduce the time someone has their first cigarette. To reduce access to tobacco products, changes such as limiting advertisements and raising the cost of these products can be made. Additionally, men tend to smoke at a higher prevalence than women, therefore it is important to do all we can to reduce their access to tobacco products. Reducing exposure to radon and encouraging others to be screened for lung cancer as recommended can also decrease the rate of lung cancer at the community level. Many programs and resources are in place in order to decrease lung cancer rates including Cancer and Tobacco Control Programs and Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs. This includes the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program and the National Tobacco Control Program which provide both funding and support to state health departments. The cancer and tobacco control programs work to build and maintain tobacco control programs that prevent and reduce the use of tobacco. The evidence-based cancer control programs give healthcare practitioners easy access to evidence-based cancer control interventions (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022).

At the policy level, The National Radon Action Plan (NRAP) is in place to prevent and fix high radon levels in indoor buildings, preventing about 3,500 lung cancer deaths per year. The NRAP started in 2015 and has since broadened its goals to achieve by 2025. They are currently working to broaden to scope of work and incorporating radon requirements into housing regulations to have a greater impact (Environmental Protection Agency, 2022).

The interpersonal level can improve lung cancer rates by encouraging men to be screened when they show symptoms. Encouraging others to stop smoking and to avoid exposure to radon, asbestos, or secondary smoke can also decrease lung cancer rates. Many times, encouraging others to stop smoking is not enough. In situations like this, it is important to find a way that will have a larger impact on the person at risk. This can include influencing the man’s children to convince their father to stop smoking. Overall, these risk factors are preventable and can play a major role in decreasing the incidence of lung cancer globally.

Key Takeaways

- Smoking drastically increases your risk of lung cancer and is the biggest preventable risk factor.

- African American men have the highest incidence of lung cancer and Hispanic men have the lowest incidence of lung cancer.

- Treatment for older patients is focused on palliative care whereas younger patients undergo aggressive treatment in order to be cancer free.

Review Questions

- Which of the following are risk factors associated with lung cancer?

- A. smoking

- B. asbestos exposure

- C. Secondhand smoke

- D. All of the above

- What stage of cancer has spread to most of the organs and is the most severe?

- A. Stage 2

- B. Stage 4

- C. Stage 3

- D. Stage 1

- Which racial/ethnic group has the lowest incidence of developing lung cancer?

- A. Caucasian men

- B. African American men

- C. Hispanic men

- D. Asian men

- Screening criteria commonly requires people to be between the ages of _______ to be screened for lung cancer.

- A. 50 and 80

- B. 30 and 60

- C. 30 and 80

- D. 60 and 80

- Small cell lung cancer is usually treated with which of the following?

- A. Surgery

- B. Chemotherapy

- C. Radiotherapy

- D. There is no treatment

References

American Cancer Society. (2019). Lung cancer signs & symptoms: Common symptoms of lung cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html

American Cancer Society. (2022).Lung cancer statistics: How common is lung cancer? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html#:~:text=Overall%2C%20the%20chance%20that%20a,t%2C%20the%20risk%20is%20lower.

American Lung Association. (n.d.). Tobacco use in racial and ethnic populations. https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/smoking-facts/impact-of-tobacco-use/tobacco-use-racial-and-ethnic

American Lung Association. (n.d.). Types of lung cancer. Lung Cancer Basics. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/lung-cancer/basics/lung-cancer-types#:~:text=What%20Are%20the%20Types%20of,cell%20lung%20cancer%20(NSCLC).

Cancer Treatment Centers of America. (2022). What is cancer, is it common & how do you get it. https://www.cancercenter.com/what-is-cancer#:~:text=Cancer%20is%20the%20uncontrolled%20growth,of%20tissue%2C%20called%20a%20tumor.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, September 22). Lung cancer: what are the risk factors. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/risk_factors.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, October 25). How communities can help people lower their lung cancer risk. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/communities.htm

Columbia University. (2018, December 5). Study looks at tobacco marketing in low-income communities. Public Health- Columbia. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/study-looks-tobacco-marketing-low-income-communities

Decoster, L., Kenis, C., Schallier, D., Vansteenkiste, J., Nackaerts, K., Vanacker, L., Vandewalle, N., Flamaing, J., Lobelle, J. P., Milisen, K., De Grève, J., & Wildiers, H. (2017). Geriatric assessment and functional decline in older patients with lung cancer. Lung, 195(5), 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-017-0025-2

Environmental Protection Agency. (2022). The National Radon Action Plan – A Strategy for Saving Lives. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/radon/national-radon-action-plan-strategy-saving-lives

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance. (2002). 3 effects of health insurance on health . National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220636/

Liu, B., Quan, X., Xu, C., Lv, J., Li, C., Dong, L., & Liu, M. (2019). Lung cancer in young adults aged 35 years or younger: A full-scale analysis and review. Journal of Cancer, 10(15), 3553–3559. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.27490

MacLean, A., Hunt, K., Smith, S., & Wyke, S. (2017). Does gender matter? an analysis of men’s and women’s accounts of responding to symptoms of lung cancer. Social Science & Medicine, 191, 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.015

Mayo Clinic. (2020, October 10). Lung cancer. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lung-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20374620

Meza, R., Meernik, C., Jeon, J., & Cote, M. L. (2015). Lung cancer incidence trends by gender, race and histology in the United States, 1973–2010. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121323

Price, S. N., Flores, M., Hamann, H. A., & Ruiz, J. M. (2021, July 7). Ethnic differences in survival among lung cancer patients: A systematic review. JNCI cancer spectrum. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8410140/

Ryan B. M. (2018). Lung cancer health disparities. Carcinogenesis, 39(6), 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgy047

Sosa, E., D’Souza, G., Akhtar, A., Sur, M., Love, K., Duffels, J., Raz, D. J., Kim, J. Y., Sun, V., & Erhunmwunsee, L. (2021). Racial and socioeconomic disparities in lung cancer screening in the United States: A systematic review. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(4), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21671

Venuta, F., Diso, D., Onorati, I., Anile, M., Mantovani, S., & Rendina, E. A. (2016, November). Lung cancer in elderly patients. Journal of thoracic disease. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5124601/

the proportion of people in a treatment group still living after a given amount of time