11 Tobacco Use

Abby Frank

The use of tobacco in any of its forms is dangerous for all populations. Now that so many different forms of tobacco exist, user rates are higher than ever. Effects can be short term, or they can impact a person for the duration of their life. One of the biggest reasons why tobacco is such a dangerous drug is its nicotine content. Tobacco contains high amounts of nicotine, a highly addictive chemical. Nicotine activates the brain to release dopamine, a chemical that signals pleasure. This immediate release of dopamine is what causes people to become addicted. It only takes a little bit of nicotine to cause addiction which is why products that contain this chemical, like tobacco, are so incredibly dangerous. Nicotine addiction may lead to increased risk of ADHD and other cognitive disorders especially as the brain continues to develop (Truth Initiative, 2022). Other health risks from using tobacco include lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema, damaging of the inner walls of the alveoli. These diseases may take years to develop whereas other diseases that result from tobacco use, such as COVID-19 may show up immediately. COVID-19 is a respiratory disease, affecting primarily the lungs. Using tobacco in any form decreases lung function which makes it difficult for the body to defend itself against respiratory diseases (World Health Organization, 2020). Using tobacco can lead to an increased risk of COVID-19, and an increase in the severity of the disease if contracted (Yang et al., 2021).

How is Tobacco Used?

There are three main ways to use tobacco: smoking, chewing, and sniffing. The most common of the three, smoking, encompasses everything from cigarettes and cigars to hookahs, pipes and e-cigarettes. This form of tobacco is harmful to not only the user, but to those around the user as well. Those who spend significant time around someone who smokes are at an increased risk of secondhand smoke. Secondhand smoke can lead to the same health issues as smoking including heart disease and lung cancer. Chewing tobacco, snuff, and dip are examples of tobacco products that are chewed. One tobacco chewing product, snuff, can also be sniffed. In addition to the health effects of traditional smoked tobacco, chewing tobacco can cause an individual to be at an increased risk of mouth cancers (National Institute of Health, 2021).

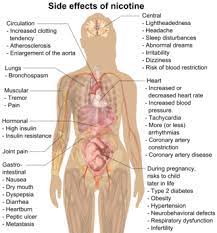

This image shows potential side effects of nicotine on the body. It is a good visual representation of how harmful nicotine can be on all body systems.

“Possible Side Effects of Nicotine” by Mikael Haggstrom is in the Public Domain, CC0

Because the dangers of tobacco use are so severe, prevention and treatment measures are constantly in the works. In 2018, the FDA outlined plans to lower the amount of nicotine in cigarettes to be less than an addictive amount (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). While this has not happened yet, organizations are still pushing for this implementation. Should this plan go into effect, it may reduce tobacco addiction. Treatment measures range from different campaigns to medications all aimed at helping people quit tobacco use, including NRT gum, nasal sprays, and patches (Truth Initiative, 2022).

Male Specific Tobacco Statistics

When looking at tobacco use among men, across the board they show higher rates than women. It is estimated that worldwide, 36.6% of men are smokers compared to 7.5% of women (Kondo et al., 2019). A possible explanation for this is that men’s neuro pathways are more rewarded from smoking than women’s which suggests that nicotine affects men more strongly. (National Institutes of Health, 2021). Because men are more likely to smoke for the effects of nicotine, they are much more likely to become addicted which could be the reason their tobacco use rates are so much higher. Men also do not respond as well to short term medications taken to help quit smoking, making the medications less effective. There is more than just cigarette smoking to consider when looking at tobacco use among men. Smokeless tobacco is also prevalent. This encompasses chewing tobacco, snuff, dip and snus. Five out of every 100 men use smokeless tobacco, whereas less than one out of 100 women use smokeless tobacco (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Men who use tobacco are at increased risk for many health problems, both short term and long term. Smoking and tobacco use can lead to increased insulin resistance, higher blood pressure, increased risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke, and even incident heart failure. Smoking can also cause a decline in cognitive function and lead to premature memory loss for middle aged men (Kondo et al., 2019).

Differing Tobacco Use Rates Across Various Life Stages

Men’s tobacco use varies depending on one’s life stage. Adolescent years are some of the most crucial for brain development. Parts of the brain responsible for emotional development experience their biggest growth in this life stage, whereas the parts of the brain responsible for cognitive control continue to develop beyond adolescence and into adulthood. Adolescents tend to act on their emotions, are highly motivated by rewards, and tend to disregard the future consequences of their decisions. Those in the adolescent life stage also experience an enhanced sensitivity to nicotine. Adolescents show higher rates of tobacco use compared to other stages of life including middle aged and elderly. A 2016 survey showed that 23.5% of male high school students reported current use of any tobacco products (e.g., cigarettes, cigars, hookahs, smokeless tobacco and electronic cigarettes). The most common tobacco product among males at this age was the electronic cigarette (Jamal et al., 2017). The appeal of electronic cigarettes is concerning, because even very low levels of e-cigarette consumption can be enough to cause addiction, and this makes it very difficult to quit smoking. Addiction can begin within 1-2 days of first smoking a cigarette (Goriounova & Mansvelder, 2012). The combination of on-going brain development and an increased sensitivity to nicotine are drivers for such high rates of tobacco use among males in the adolescent stage of life.

As of 2016, 19.3% of U.S. middle-aged men (45-64 years old) were said to be current cigarette smokers compared to 10.1% of men aged 65 and older (Jamal et al., 2018). While there could be a variety of explanations for this difference, the daily stresses of life are a potential contributing factor to the high prevalence of smoking among middle-aged men. Smoking causes the brain to release dopamine, a chemical that signals pleasure. This may cause men to crave the rewards of nicotine to cope with stressful workdays. On the other hand, a more relaxed, less stressful retirement lifestyle is common for elderly adults. These decreased stress levels may result in lower nicotine cravings for elderly men. This may be the reason for the drop in tobacco use among men in the retirement stage of life compared to those in middle-age.

This image depicts a man smoking a cigarette. This image relates to my chapter as it is about the use of tobacco among men, and cigarettes are one of many forms of tobacco.

“Man With Mustache Smoking” by Adam Cohn is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Tobacco Use Based on Education Level

Tobacco use rates among men also vary by education level. Generally, men with more education are less likely to smoke or use any form of tobacco. Statistics show that 32% of those with a GED, 17.6% of those with high school diplomas, 12.7% of those with an associate degree, 5.6% of those with bachelor’s degrees, and 3.5% of those with a graduate degree are current tobacco users (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Programs taught in school that are centered around teaching life skills, information on smoking, and how to overcome social influences may be linked to a reduction in the number of smokers. This is true not only for the U.S. but for other countries as well. In Indonesia, smoking is a highly accepted cultural practice among people of all ages. However, various comprehensive smoking prevention programs helped to not only increase students’ knowledge of smoking, but to create an anti-smoking attitude. This helped to reduce intentions of smoking in the future (Tahlil et al., 2013). Having access to resources that expose the dangers of tobacco use in school could be a reason for the differences in tobacco use among those with different education levels. Another potential explanation as to why men with higher education levels exhibit lower smoking rates may have to do with income. A lower education level could correlate with a lower income level. Financial stress could cause some men to turn to smoking as a coping mechanism, just as middle-aged men may turn to smoking to cope with the stresses of work. There are many intersections that can be looked at when examining tobacco use rates among men. Stage of life and education level are two prominent ones, and each has their individual reasons for the disparities seen in the rates of tobacco use.

Strategies to Reduce Male Tobacco Use

Because tobacco use is an on-going concern among all populations, there are constantly prevention strategies in the works to try and combat this health issue. One such strategy is a campaign entitled “Tips from Former Smokers”. This campaign works to increase the accessibility of free resources focused on helping people quit smoking, while also addressing health disparities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). They want to be sure that regardless of one’s racial background, how much money a person makes, or where they are from, they all have access to these helpful resources. This prevention strategy could positively impact those with a lower income which may include those with a lower education level. People may not be aware that there are resources out there that cost very little or nothing at all, and this campaign is working to change that. “Tips from Former Smokers” works to make resources known and accessible to any and all social groups of people.

Over the years, policies regarding tobacco and cigarette use have been put in place to try and decrease overall usage, especially in public settings. These policies affect those of all life stages and education levels. 23 states as well as 93 localities have all passed laws that prohibit indoor smoking (Paoletti et al., 2012). In South Carolina, the Clean Indoor Air Act was passed which prohibits smoking of any kind in all indoor public areas except where there is a designated smoking area (US Legal, 2022). As more research about the harmful effects of tobacco came out, Congress began passing a variety of acts concerning the dangers of tobacco. In 1969, an act known as the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act prohibited cigarette advertising in the broadcast media. Eventually, cigars and smokeless tobacco products would be included in this act as well. In 1984, the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act went into effect which required health warnings to be put on all cigarette packages and advertisements. These acts and policies have made tobacco less affordable and socially acceptable and have caused user rates to gradually decrease.

Strategies of the 21st Century

In 2008, the WHO introduced a new strategy known as the MPOWER package across the world (Peruga et al., 2021). MPOWER is made up of six measures which include monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies, protecting people from tobacco smoke, offering to help quit tobacco use, warn about the dangers of tobacco, enforce bans on tobacco promotion, and raise taxes on tobacco. Every country is scored based on how close they are to the highest level of policy on each of the six measures. Many countries and populations around the world are benefiting from one or more of these measures, and are seeing declines in tobacco use.

There are not strategies regarding tobacco use that target specifically males. However, since the policies and laws put in place have impacted tobacco use rates on all of the general public, it can be assumed that male tobacco use rates have therefore also decreased. Though tobacco use is still a prevalent issue among men as well as other populations, knowing that implementing policies has worked in the past gives hope for the future.

Key Takeaways

- Tobacco use remains a prevalent health issue among men across all stages of life and education levels.

- Coping with stress may be a reason for tobacco use when looking at both men with a lower education level and middle-aged men.

- Laws and policies that were put in place overtime seem to have been successful in lowering the rates of tobacco use among men. There are still strategies in the works to lower user rates even more.

Chapter Review Questions

-

- What is the most common way to use tobacco?

- A. Sniffing

- B. Smoking

- C. Chewing

- D. IV use

- Which of the following life stages is shown to have the highest percent of tobacco users?

- A. Adolescence

- B. Middle-aged

- C. Elderly

- D. Toddlers

- What did the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act require?

- A. The ban of tobacco products indoors

- B. The implementation of tobacco prevention programs in schools

- C. Warning labels to be placed on all cigarette packs and advertisements

- D. A required class on the types of tobacco

- What is the goal of the campaign “Tips from Former Smokers”?

- A. Bringing awareness to resources that aid in quitting smoking

- B. Selling tobacco products

- C. Giving informative lectures on the dangers of tobacco

- D. Banning tobacco from the U.S.

- What is the most common way to use tobacco?

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, March 18). Smokeless Tobacco Product Use in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/smokeless/use_us/index.h tm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, September 5). Tips From Former Smokers. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/index.html?s_cid=OSH_tips_GL0008&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=TipsRegular+2021%3BS%3BWL%3BBR%3BIMM%3BDTC%3BCO&utm_content=Smoking+-+Prevention_E&utm_term=prevention+of+smoking&gclid=CjwKCAjws–ZBhAXEiwAv-RNLzBzTT4-rSYywV0822-s-K5NVvfL6JGh8g4kJnbgXVMGpN_wUyuzNhoCks0QAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds.

Evans-Polce, R., Vasilenko, S., Lanza S. (2015). Changes in gender and racial/ethnic disparities in rates of cigarette use, regular heavy episodic drinking, and marijuana use: Ages 14 to 32. Science Direct, 41(), 218-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.029.

Goriounova, N. A., & Mansvelder, H. D. (2012). Short- and long-term consequences of nicotine exposure during adolescence for prefrontal cortex neuronal network function. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 2(12), a012120. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a012120.

Jamal, A., Gentzke, A., Hu, S. S., Cullen, K. A., Apelberg, B. J., Homa, D. M., & King, B. A. (2017). Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students – United States, 2011-2016. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 66(23), 597–603. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6623a1

Jamal, A., Phillips, E., Gentzke, A. S., Homa, D. M., Babb, S. D., King, B. A., & Neff, L. J. (2018). Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults – United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 67(2), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1

Kondo, T., Nakano Y., Adachi S., Murohara T. (2019). Effects of tobacco smoking on cardiovascular disease. Circulation Journal, 83(10), 1980-1985. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0323

National Institute of Health. (2021, April). Cigarettes and tobacco products DrugFacts. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/cigarettes-other-tobacco-products.

Paoletti, L., Jardin, B., Carpenter, M. J., Cummings, K. M., & Silvestri, G. A. (2012). Current status of tobacco policy and control. Journal of thoracic imaging, 27(4), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1097/RTI.0b013e3182518673

Peruga, A., López, M. J., Martinez, C., & Fernández, E. (2021). Tobacco control policies in the 21st century: achievements and open challenges. Molecular oncology, 15(3), 744–752. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.12918

Tahlil, T., Woodman, R. J., Coveney, J., & Ward, P. R. (2013). The impact of education programs on smoking prevention: a randomized controlled trial among 11 to 14 year olds in Aceh, Indonesia. BMC public health, 13, 367. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-367

Truth Initiative. (2022, June 8). Nicotine and the young brain. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/harmful-effects-tobacco/nicotine-and-young-brain.

US Legal. (2022). Smoking Regulations in South Carolina. https://smoking.uslegal.com/smoking-regulations-in-south-carolina/

World Health Organization. (2020, May 11). WHO statement: tobacco use and COVID-19. https://www.who.int/news/item/11-05-2020-who-statement-tobacco-use-and-covid-19

Yang, Y., Lindblom, E. N., Salloum, R. G., & Ward, K. D. (2021). Perceived health risks associated with the use of tobacco and nicotine products during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tobacco induced diseases, 19, 46. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/136040