16 Unhealthy Drinking Habits

Emma Goerl

Unhealthy consumption of alcohol is a key risk factor for many health problems. Although all alcohol consumption has contributed to the global burden of disease, it is consistent heavy drinking that has the greatest negative impact. The Centers for Disease Control (2019) defines heavy drinking as “consuming 8 or more drinks a week for women and 15 or more drinks a week for men”. This may include binge drinking, which is a regular habit of drinking about 5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more drinks for women in a span of 2 hours (College Drinking, 2021). A habit of heavy drinking may cause alcohol dependence or abuse. The National Cancer Institute (n.d.) defines alcohol dependence as a chronic disease causing an individual to crave alcohol to the point of experiencing withdrawal symptoms if alcohol is not drunk. Additionally, alcohol abuse is the term used to define an individual who overly consumes alcohol (i.e., binge drinking) to the point that it impacts daily functioning.

There are many health risks linked to alcohol consumption. One of the most common risks is cancer, causing about 4% of all cancers globally. Furthermore, alcohol is known to increase the risk of liver, breast, and colorectal cancers (Rumgay et al., 2021).

This image charts the increase in health risks as the standard number of drinks per day.

“Data source: Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories” is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

However, the poor effects of alcohol consumption do not stop at cancer. Recent studies show that alcohol use can also increase the chances of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases (Masip & Lluch, 2019). These health risks prove that, when abused, alcohol has negative effects on overall health and well-being and is a public health issue that needs to be addressed.

Since alcohol dependence and abuse is a complex topic with many factors influencing it, it is important to create intervention plans from many different angles. Prevention at the policy level has had positive results (Mäkelä et al., 2015), but greater work needs to be done on other levels, such as the organizational level (i.e., the workplace, schools, churches).

ALCOHOL USE IN MEN

There are many factors that predispose individuals to alcohol abuse, and among those factors is gender. Studies have shown that men usually have higher rates of alcohol use and binge drinking in comparison to women, with the greatest risk among older men. In fact, in the United States, male drinkers typically have about three times as much pure alcohol as women do (White, 2020). Globally, about 107 million people have an alcohol use disorder, but 70% of those suffering are men (Ritchie & Roser, 2018).

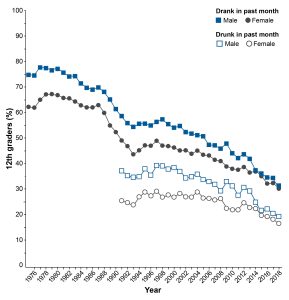

This image compares alcohol use rates between men and women in the United States.

“Gender Differences in the Epidemiology of Alcohol Use and Related Harms in the United States” by Aaron M. White is in the Public Domain,

RACE AND ALCOHOL

Since men are struggling with alcohol use and are suffering from the consequences, it is important to look at factors beyond gender that influence these rates. One of the most studied factors is racial background. A recent study observed that Whites reported the highest prevalence of recent alcohol consumption; however, Native Americans showed the highest rates for alcohol dependence and abuse. In addition, both Native Americans and African Americans were the most at risk for alcohol-related health outcomes (Delker et al., 2016).

Another study found that although Blacks were less likely to drink over the span of their lives, among those that did drink were most likely to binge drink. In contrast, White individuals were less likely to binge drink, but more likely to drink consistently over time (Pamplin et al., 2020). These patterns show that that males of a minority race are most at risk for these unhealthy drinking habits, as well as the health risks that follow.

INCOME AND ALCOHOL

Another factor that affects alcohol use rates among men is income and socioeconomic status (SES). Elliot and Lowman (2015) suggest that people of higher SES and income typically abuse alcohol less, due to an internal locus of control. This means that they feel in control of their lives. In contrast, those of a lower SES have more of an external locus of control, believing their lives are controlled by luck. This external locus of control decreases their sense of personal control and is linked to greater alcohol use. Thus, this study found that those of lower income were more likely to become alcohol dependent (Elliot et al., 2015). However, it is important to note that some factors may protect against unhealthy alcohol consumption. For example, research shows that religious affiliations are protective against alcohol abuse for people of a lower SES, more so than those with higher SES (Elliot et al., 2015).

An important piece that influences income is level of education. Baker (2014) explains that higher education is associated with higher SES and income, and that more educated people are healthier due to their ability to recognize health risks. Additionally, higher income is related to overall better health (Baker, 2014), which demonstrates that even when those of lower income and SES consume less alcohol, they experience worse health effects (Collins, 2016). For these reasons, it will be important to use prevention methods on an educational level.

Since men are two times more likely to experience financial stress (Parker & Stepler, 2017), the impact that low income and low SES can have specifically on men is damaging. Financial stress, and other forms of stress, can often lead to unhealthy coping mechanisms. Unfortunately for men, one of those top mechanisms is consuming alcohol.

PREVENTION AT THE POLICY LEVEL

PREVENTION AT THE ORGANIZATION LEVEL

Prevention at the organization level involves techniques used in workplaces, schools, churches, and other organizations. Targeting men outside of their home life, and in an organization with their peers, is a beneficial way to provide help. One study looked at religious involvement and how it influences alcohol use among African American populations (Busby et al., 2021). Although the study found that religious involvement might not decrease alcohol use, it does recognize the important effect these organizations can have on alcohol use, especially among minority populations. Furthermore, Roman and Blum (n.d.) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism explain that the workplace provides strong potential for prevention programs. One strategy already successful is the use of the employer assistance programs (EAPs). EAPs offer confidential assessments, counseling, and follow-up services to support employee health and maintain productivity.

Moving forward, it is crucial to expand prevention programs on both policy and organizational levels, due to their present success. However, it would also be beneficial to utilize prevention at the interpersonal level, as numerous studies have shown that interpersonal interactions with family members, friends, and those in the immediate community have a strong impact on alcohol consumption, especially among racial minorities (Busby et al., 2021). Working to provide all men with a supportive and caring community can positively influence drinking habits and their overall health.

Key Takeaways

- Heavy drinking is defined as consuming 8 or more drinks a week for women and 15 or more drinks a week for men.

- 70% of those with alcohol use disorder globally are men.

- Native Americans have the highest prevalence for alcohol dependence and abuse. Meanwhile, those of low incomes and low SES are most susceptible to unhealthy drinking habits.

Chapter Review Questions

- About ___ of all cancers globally are caused by alcohol consumption.

- A. 21%

- B. 4%

- C. 15%

- D. 8%

- True or False: alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence are the same thing.

- A. True

- B. False

- ____ were the most susceptible to alcohol-related health risks and consequences.

- A. Native Americans

- B. Whites

- C. African Americans

- D. A & C

- Which level of prevention has proven to be effective against alcohol consumption?

- A. Intrapersonal

- B. Community

- C. Policy

- D. Interpersonal

references

Baker, E. H. (2014). Socioeconomic status, definition. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Health, Illness, Behavior, and Society, 2210–2214. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118410868.wbehibs395

Busby, D. R., Hope, M. O., Lee, D. B., Heinze, J. E., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2021). Racial discrimination and trajectories of problematic alcohol use among African American emerging adults: The role of organizational religious involvement. Health Education & Behavior, 49(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/10901981211051650

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, December 30). What is excessive alcohol use? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/onlinemedia/infographics/excessive-alcohol-use.html#:~:text=Heavy%20drinking%3A%20For%20women%2C%20heavy,drinks%20or%20more%20per%20week.

Chartier, K., & Caetano, R. (2010). Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 33(1-2), 152–160.

College drinking. (n.d.). Retrieved October 08, 2022, from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/college-drinking

Delker, E., Brown, Q., & Hasin, D. S. (2016). Alcohol Consumption in Demographic Subpopulations: An Epidemiologic Overview. Alcohol research : current reviews, 38(1), 7–15.

Elliott, M., & Lowman, J. (2015). Education, income and alcohol misuse: a stress process model. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 50(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0867-3

Mäkelä, P., Herttua, K., & Martikainen, P. (2015). The Socioeconomic Differences in Alcohol-Related Harm and the Effects of Alcohol Prices on Them: A Summary of Evidence from Finland. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 50(6), 661–669. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv068

Masip, J., & Germà Lluch, J. R. (2021). Alcohol, health and cardiovascular disease. Revista clinica espanola, 221(6), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rceng.2019.07.001

Pamplin, J. R., 2nd, Susser, E. S., Factor-Litvak, P., Link, B. G., & Keyes, K. M. (2020). Racial differences in alcohol and tobacco use in adolescence and mid-adulthood in a community-based sample. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 55(4), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01777-9

Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2018, April 16). Alcohol consumption. Our World in Data. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://ourworldindata.org/alcohol-consumption

Roman, P. M., & Blum, T. C. (n.d.). The workplace and Alcohol Problem Prevention. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh26-1/49-57.htm

Rumgay, H., Murphy, N., Ferrari, P., & Soerjomataram, I. (2021). Alcohol and Cancer: Epidemiology and Biological Mechanisms. Nutrients, 13(9), 3173. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093173

Wagenaar, A. C., Salois, M. J., & Komro, K. A. (2009). Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 104(2), 179–190. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02438.x

White, A. (2020). Gender differences in the epidemiology of alcohol use and related harms in the United States. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40(2). https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.2.01