14 Colorectal Cancer

Alyssa Sheppard

Structure and Function

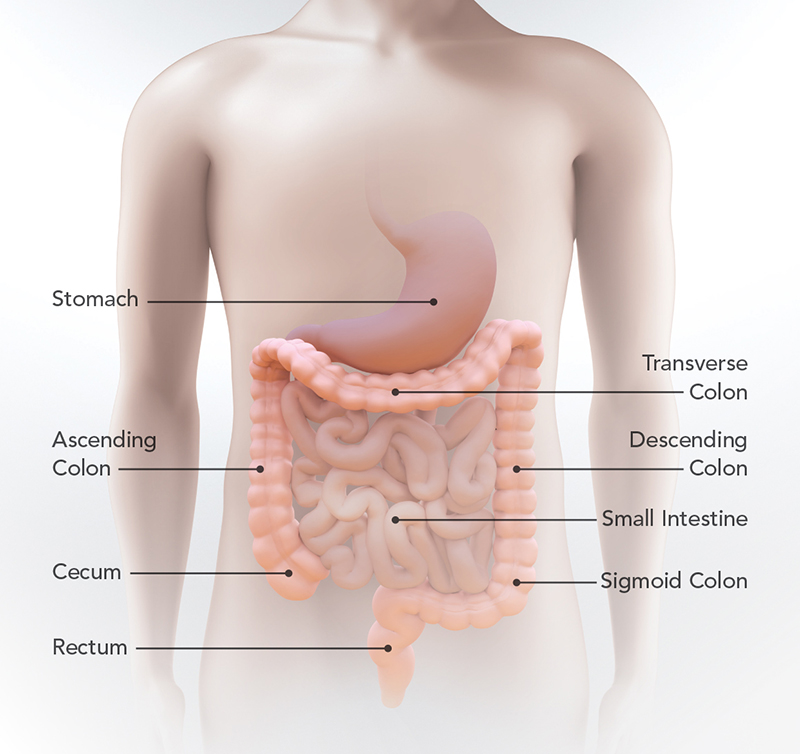

Colorectal cancer, or CRC, is a form of cancer that begins in the colon or the rectum (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2020f). These are two different types of cancer but are grouped since they have similar traits. The colon and rectum make up the large intestine. The large intestine and the small intestine play a large role in the human digestive system. Most of the large intestine is the colon which has four parts: ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon. The sigmoid colon connects to the rectum and allows for waste disposal by the anus (ACS, 2020f).

The colon’s job is to soak up water and salt from the undigested food of the small intestine (ACS, 2020f). The remaining waste travels through the colon and into the rectum. The waste stays in the rectum until it leaves the body through a bowel movement. The colon plays an important role in food digestion, yet the formation of cancer makes it difficult for the colon and rectum to do their job (ACS, 2020f).

Colorectal cancer typically begins as a growth on the inner lining of the colon or rectum (ACS, 2020f). The growths are known as polyps and can be cancerous based on the type. Some polyps change into cancer over time, while other polyps remain cancer-free. Cancer risk increases if a polyp is larger than 1 cm, if more than three polyps exist, or if dysplasia remains after polyp removal (ACS, 2020f). If a polyp is cancerous, cancer will begin to grow at the mucosal layer of the colon. Depending on the cancer type, the polyp will stay inside the colon or spread to other organs by the bloodstream or lymphatic system. The extent of colorectal cancer depends on how deeply it grows in the body tissues and how far it spreads (ACS, 2020f).

Risk Factors

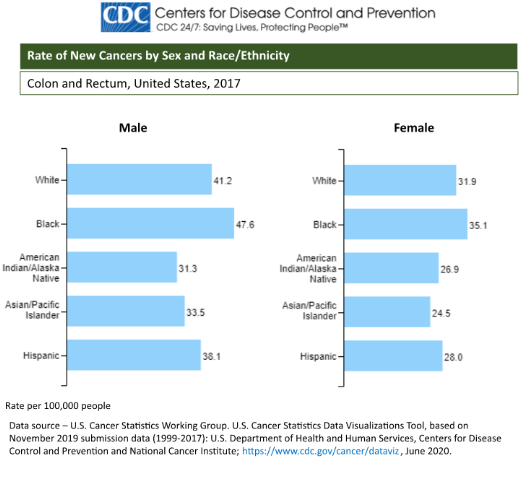

Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer mortality in the U.S. and is the third most common type of cancer for men and women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). Although colorectal cancer shares the same ranking for men and women, this type of cancer is more common among men. Compared to women, men have more cases of CRC and larger death rates. According to White et al. (2018), men are at a greater risk for colorectal cancer due to gender-related behavior like diets high in red meat or fat, increased alcohol use, and smoking compared to women. Other risk factors include a family history of colorectal cancer, irritable bowel syndrome, race and ethnicity, and age (ACS, 2020c).

Prevention

There are currently two prevention strategies for CRC: primary and secondary prevention. Around 70% of CRC cases, in theory, are due to lifestyle factors like diet, level of physical activity, and location of fat as mentioned in the abdominal obesity chapter (Roncucci & Mariani, 2015). The target of primary prevention is the general population, specifically people who are at risk due to their lifestyle. The recommendation at the population level is to be physically active every day, be within a normal BMI range, limit red meat intake, eat a variety of fiber-rich food, and avoid alcohol use or smoking (Roncucci & Mariani, 2015). A lifelong healthy lifestyle is important for CRC prevention.

Secondary prevention focuses on people at an average or higher risk for CRC due to age, family history of colorectal syndromes, and people with irritable bowel syndrome (Roncucci & Mariani, 2015). The goal of secondary prevention is to catch CRC cancer early to improve the chances of survival. It is important that adults older than 45 should have regular CRC screening through national programs. People who carry the gene for CRC have a higher risk of developing cancer during their lifetime and should get a colonoscopy every one to two years starting at ages 20-25. In addition, people with irritable bowel syndrome should begin to have colonoscopies 10 years after diagnosis to monitor abnormal cell growth. In conclusion, living a healthy lifestyle and regular screening are the recommended prevention strategies for CRC (Roncucci & Mariani, 2015).

Symptoms of Colorectal Cancer

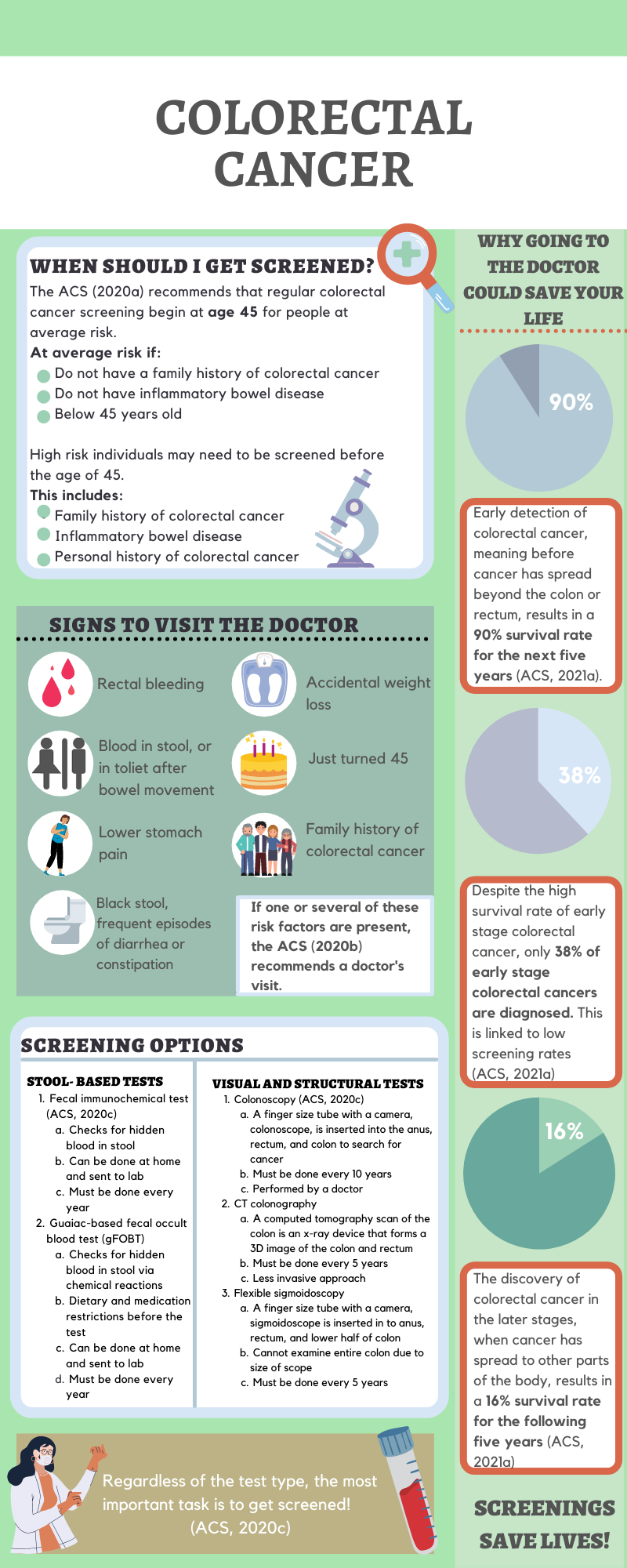

The American Cancer Society (2020b) states that the early stages of colorectal cancer often show no symptoms, highlighting the importance of regular screening for cancer detection and survival. Although most CRC cases are found in adults 55 years old or older, the number of cases is steadily rising in young adults. For example, in 2020, an estimated 17,930 adults under 50 were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, which is equal to 49 new cases each day. Common digestive symptoms are rectal bleeding, blood in the stool or the toilet after a bowel movement, black stool, or frequent constipation and diarrhea. Other symptoms include cramping or pain in the lower stomach, accidental weight loss, and decreased appetite. If any of these symptoms are present, it is necessary to contact a physician to figure out the cause. Therefore, if any of these symptoms are present it is crucial to seek medical attention for the overall survival of CRC.

Screening Options

In 2018, the American Cancer Society (2020b) lowered the recommended screening age from 50 to 45 due to CRC cases increasing in younger populations. Colorectal cancer can be diagnosed by sensitive stool-based tests or visual exams of the colon and rectum. Patients should discuss each test type with their doctor to select the best option based on their health. The ability for patients to choose from a variety of screening tests has substantially increased regular screening among the population. The American Cancer Society does not favor a single test type and promotes several screening options to encourage everyone to get tested.

The American Cancer Society (2020d) recommends two types of stool-based tests called the high-sensitivity guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOTB) and the fecal immunochemical test (FIT). As the stool exits the rectum, friction with cancer polyps can cause blood to appear in feces. Both tests examine the stool for hidden blood and require completion each year. The gFOTB and FIT screenings occur at home through a collection kit service, and the sample is sent to the lab for analysis. The main difference between the test types is that the gFOTB requires dietary restrictions before sample collection. People who select this test should avoid vitamin c, NSAIDs, and red meat a week before collection for accurate results. In comparison to other screening options, stool-based tests do not require a doctor’s visit, low cost, and a less invasive approach (ACS, 2020d). The regular use of the gFOTB led to a 20% decrease in CRC formation and a 32% decrease in CRC death (ACS, 2020b).

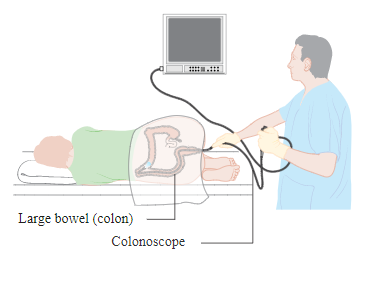

Visual screening techniques for CRC include colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and computed tomography colonography (ACS, 2020b). Doctors can view the inner lining of the colon and rectum by using an endoscope or x-ray imaging. The endoscopic techniques are colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy. An endoscope is inserted into the anus, rectum, and colon to search for polyps. (ACS, 2020b). The major difference between the tests is that the sigmoidoscopy device can only visualize one-third of the colon, but the colonoscopy device can display the entire colon. The testing recommendation for colonoscopy is every ten years and every five years for a sigmoidoscopy. According to the American Cancer Society (2020b), a colonoscopy reduces CRC occurrence by 40% and cancer death by 60%. A sigmoidoscopy reduces CRC onset by 20-25% and cancer death by 25-30%. The use of sigmoidoscopy led to a greater reduction in CRC death in men than women, so this is important to consider when choosing a screening method. A computed tomographic colonography builds 3D images of the colon from x-rays. This method takes place every five years and offers a less-invasive option for patients. (ACS, 2020b). Regardless of the test type, screening plays a key role in colorectal cancer detection and potential treatment options (Lauby-Secretan et al., 2018).

Treatment

Treatment for colorectal cancer depends on the cancer stage when diagnosed and location. The American Cancer Society (2020e) describes common treatment options like surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. Surgery is the main treatment option for colon and rectal cancers that have not metastasized. (ACS, 2020e). Most early-stage colon and rectal cancers are removed during a colonoscopy to avoid major surgery. A polypectomy removes cancer by cutting the polyp off the inner lining, while a local excision removes the polyp and surrounding healthy tissue (ACS, 2020e). If cancer has metastasized, treatment involves a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. The goal of chemotherapy and radiation is to shrink tumors to a smaller size for surgical removal. When cancer has spread beyond the possibility of removal, chemotherapy becomes the primary course of treatment for colon and rectal cancers (ACS, 2020e).

Early diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer result in a 90% survival rate for the next five years (ACS, 2021a). In comparison, when colorectal cancer is found in the later stages, the five-year survival rate for rectal cancer is 16% and 14% for colon cancer (ACS, 2021a). Regular screening is essential for the early detection and treatment of colorectal cancer. Currently, only 38% of colorectal cancers are caught in the early stages, partly due to lack of screening. (ACS, 2021a). Increasing awareness of the variety of screening techniques and risk factors can improve screening habits and overall survival of CRC (ACS, 2020b).

Chapter Review Questions

1. Men are at a greater risk for colorectal cancer development due to all of the following behaviors except?

A. Diets high in red meat

B. Alcohol consumption

C. Poor sleeping habits

D. Smoking

2. What is a symptom of early-stage colorectal cancer?

A. No obvious symptoms

B. Black stool

C. Rectal bleeding

D. Abdominal cramping

3. At what age does the American Cancer society recommend colorectal cancer screening?

A. 50

B. 35

C. 45

D. 60

References

American Cancer Society. (2020a, November 17). American Cancer Society guideline for colorectal cancer screening. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html

American Cancer Society (2020b). Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2020-2022. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2020-2022.pdf

American Cancer Society. (2020c, June 29). Colorectal cancer risk factors. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

American Cancer Society. (2020d, June 29). Colorectal cancer screening tests. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/screening-tests-used.html

American Cancer Society. (2020e, June 29). Colorectal cancer treatment | How to treat colorectal cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/treating.htm

American Cancer Society. (2021a). Survival rates for colorectal cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

American Cancer Society. (2021b). Text alternative for colon & rectal cancer: Catching it early. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/prevention-infographic/text-alternative-for-colon-and-rectal-cancer-catching-it-early.html

American Cancer Society. (2020f, June 29). What is colorectal cancer? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/about/what-is-colorectal-cancer.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, June 8th). Colorectal cancer statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/index.htm

Lauby-Secretan, B., Vilahur, N., Bianchini, F., Guha, N., & Straif, K. (2018). The IARC perspective on colorectal cancer screening. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(18), 1734-1740. 10.1056/NEJMsr1714643

Roncucci, L. and Mariani, F. (2015). Prevention of colorectal cancer: how many tools do we have in our basket? European Journal of Internal Medicine, 26 (10), 752-756. 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.08.019

White, A., Ironmonger, L., Steele, R. J. C., Ormiston-Smith, N., Crawford, C., & Seims, A. (2018). A review of sex-related differences in colorectal cancer incidence, screening uptake, routes to diagnosis, cancer stage, and survival in the UK. BMC Cancer, 18(1), 906. 10.1186/s12885-018-4786-7.

the part of the large intestine that extends from the cecum to the bend on the right side below the liver

the part of the large intestine that extends across the abdominal cavity joining the ascending colon to the descending colon

the part of the large intestine on the left side that extends from the bend below the spleen to the sigmoid colon

the contracted and crooked part of the colon immediately above the rectum

abnormal growth or development (as of organs or cells)

one that lines body cavities and passages (as of the gastrointestinal or respiratory tract) which communicate directly or indirectly with the outside of the body

the part of the circulatory system that is concerned especially with scavenging fluids and proteins which have escaped from cells and tissues and returning them to the blood, with the phagocytic removal of cellular debris and foreign material, and with the immune response and that consists especially of lymphoid tissue, lymph, and lymph-transporting vessels

A chronic functional disorder of the colon that is characterized especially by constipation or diarrhea, cramping abdominal pain, and the passage of mucus in the stool.

a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (such as aspirin and ibuprofen)

an illuminated usually fiber-optic flexible or rigid tubular instrument for visualizing the interior of a hollow organ or part (such as the bladder or esophagus) for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes that typically has one or more channels to enable passage of instruments (such as forceps or scissors)

any of the electromagnetic radiations that have an extremely short wavelength of less than 100 angstroms and have the properties of penetrating various thicknesses of all solids, of producing secondary radiations by impinging on material bodies, and of acting on photographic films and plates as light does

the administration of one or more cytotoxic drugs to destroy or inhibit the growth and division of malignant cells in the treatment of cancer

emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves through space or through material.

spread or growth of cancer to another part of the body