Avery Morse

Introduction

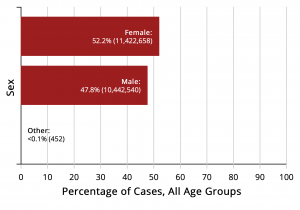

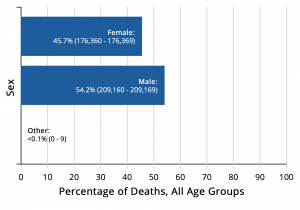

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, also known as COVID-19, is a sickness that affects the respiratory tract. It was first discovered in 2019 and has spread across the entire world. Within a year, 27 million cases were reported in the United States. And of those, there were almost half a million deaths (Center for Disease Control, 2021). Research has found that men are dying from COVID-19 at a disproportionate rate when compared to women. In Italy, the death rate of men with COVID-19 was 13.3%, compared to 7.4% for women. (Pivonello et al., 2020). Because of this difference, it is important for men to know the symptoms, why they are at a greater risk, and how they can decrease the severity of COVID-19.

What Are COVID-19 Symptoms?

Some of the virus’s most common symptoms include fever, dry cough, headaches, loss of taste and/or smell, and digestive issues (Pivonello et al., 2020). Around 80% of cases will produce these mild to moderate symptoms (Giagulli et al., 2021). Some people will develop severe symptoms that lead to hospitalizations. This is much more common in older patients or those with pre-existing medical conditions (Giagulli et al., 2021). Other cases present as asymptomatic, which means that the person experiences no symptoms and therefore is unaware that they have the virus.

Why Are Men More at Risk for Severe Disease?

Men, compared to women, are at a biological disadvantage because of their immune system’s response to this type of virus. This means that men’s and women’s bodies react differently to the virus, simply because of sex differences. Many genes that are related to the immune system and someone’s response to germs are located on the X chromosome (Pivonello et al., 2020). Women have two X chromosomes, meaning if they have a mutation on one, it is possible that the other X chromosome will hide it. Since men only have one X chromosome, if they have a mutation that disrupts their immune response it cannot be hidden (Pivonello et al., 2020). Mutations on the Y chromosome, only found in men, can also suppress the immune system response (Pivonello et al., 2020).

Additionally, testosterone has a suppressive effect on the immune system. Women have small amounts of testosterone, but not nearly as much as men. Testosterone has been shown to reduce white blood cell levels which can decrease the production of immunoglobin E, which helps the body fight off bacteria, viruses, and allergens, and is therefore very important for someone to have when fighting COVID-19 (Giagulli et al., 2021).

How Can Men Prevent Becoming Infected With COVID-19?

Because of these biological disadvantages, men need to be more proactive about other health behaviors in order to decrease their risk of developing a severe case of COVID-19. Men are more likely to participate in risky behavior which can include behaviors like not wearing masks or social distancing that could expose them to the virus more often than women. Additionally, according to the CDC, more men have reported going to social gatherings during the pandemic than women (Griffith et al., 2020). Until the majority of the world is vaccinated, it is very important that everyone, but especially men, wear protective masks in order to minimize the risk of contracting and spreading the virus.

Not only does risky behavior pose a threat to men contracting the virus, but certain pre-existing conditions can also put men at risk. According to the Australasian Journal of Medicine, two separate studies performed in Italy and New York calculated the percentage of people who died from COVID-19 that had other medical conditions. In Italy, out of 355 deaths studied, only 1 person had no other existing conditions. In New York, over 13,000 people were included in the study and 89% of them had a chronic condition. These conditions included but were not limited to: hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, chronic lung diseases, chronic kidney disease, and congestive heart failure (Cumming et al., 2020). Additionally, those with low vitamin D levels are predisposed to COVID-19. Those with this deficiency should take vitamin supplements to help boost their immune system function (Abdollahi et al., 2021). This means that men need to be more aware of their diet and negative health behaviors that can contribute to other diseases and therefore affect their likelihood of getting COVID-19.

The Importance of Vaccination

While there still is no cure for this deadly virus, vaccines are available to the general public, and they can help reduce the risk of a severe COVID-19 infection. Because of the contagious nature of COVID-19, it is very important for everyone to vaccinate, as long as they are able, in order to slow the spread of the virus. Some men can be resistant to vaccines because they can be costly, they can be painful, and they are uneducated about the benefits (Snyder, 2020). Vaccination rates can not only vary among males and females but also by ethnicity and race. Multiple studies found that around 20% of Mexican-American men regularly participated in getting the flu vaccine in 2015, which is a much lower percentage compared to other ethnic groups (Snyder, 2020). Because of this, it is important that healthcare and prevention strategies for COVID-19 target all groups of men and not generalize men into one category.

Chapter Review Questions

1. What is the most effective way to prevent a severe case of COVID-19?

A. Wearing a mask

B. Social distancing

C. Vaccination

D. Double-masking

2. What is an uncontrollable factor that puts men more at risk for contracting COVID-19?

A. Vitamin D levels

B. Mutations on chromosomes

C. Pre-existing conditions

D. Risky behaviors

3. How do chromosomes contribute to increased mutations on men’s genes?

A. Men only have one X chromosome, and it cannot be masked

B. Men’s Y chromosome has an increased likelihood of having a mutation

C. Men have more exposure to toxins that cause mutations compared to women

D. The mutations are due to higher levels of testosterone in the body compared to women

References

Abdollahi, A., Sarvestani, H. K., Rafat, Z., Ghaderkhani, S., Mahmoudi-Aliabadi, M., Jafarzadeh, B., & Mehrtash, V. (2021). The association between the level of serum 25(OH) vitamin D, obesity, and underlying diseases with the risk of developing COVID-19 infection: A case-control study of hospitalized patients in Tehran, Iran. Journal of Medical Virology., 93(4), 2359-2364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26726

Center for Disease Control. (2021). COVID data tracker. Retrieved February 14, 2021, from https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#global-counts-rates

Cumming, R., Khalatbari-Soltani, S., Blyth, F. M., Naganathan, V., & Le Couteur, D. G. (2020). Not all older men have the chronic diseases associated with severe COVID‐19. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 39(4), 381–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12839

Giagulli, V. A., Guastamacchia, E., Magrone, T., Jirillo, E., Lisco, G., De Pergola, G., & Triggani, V. (2021). Worse progression of COVID-19 in men: Is testosterone a key factor? Andrology, 9(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12836

Griffith, D. M., Sharma, G., Holliday, C. S., Enyia, O. K., Valliere, M., Semlow, A.R., Stewart, E. C., & Blumenthal, R. S. (2020) Men and covid-19: A biopsychosocial approach to understanding sex differences in mortality and recommendations for practice and policy interventions. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200247

Pivonello, R., Auriemma, R. S., Pivonello, C., Isidori, A. M., Corona, G., Colao, A., & Millar, R. P. (2020). Sex disparities in covid-19 severity and outcome: Are men weaker or women stronger? Neuroendocrinology. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1159/000513346

Snyder, V., Garcia, D., Pineda, R., Calderon, J., Diax, D., Morales, A., & Perez, B. (2020). Exploring why adult mexican males do not get vaccinated: Implications for COVID-19 preventive actions. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 42(4), 515–527. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1177/0739986320956913

Introduction

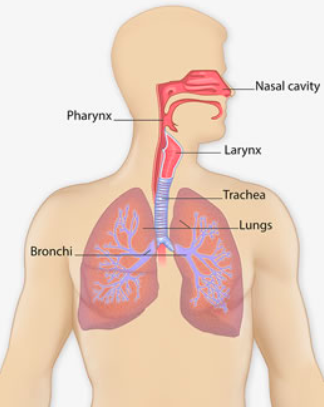

Lung cancer is a form of cancer that begins in the lungs. The lungs are spongy organs that take in oxygen and release carbon dioxide (Mayo Clinic, 2020). When humans inhale, oxygen is taken into the bloodstream where it is carried throughout the body and is traded for carbon dioxide which is a waste gas that is released when exhaled. There is a right lung and a left lung that are divided into segments called lobes. Once air enters into the lungs, it travels down branches that decrease in size starting with the bronchus and the end is the alveoli.

The alveoli are tiny air sacs where oxygen is exchanged for carbon dioxide (American Lung Association, 2020). The lungs are very important to the human body as they help humans breathe, but the presence of lung cancer makes it very difficult for the lungs to work properly.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

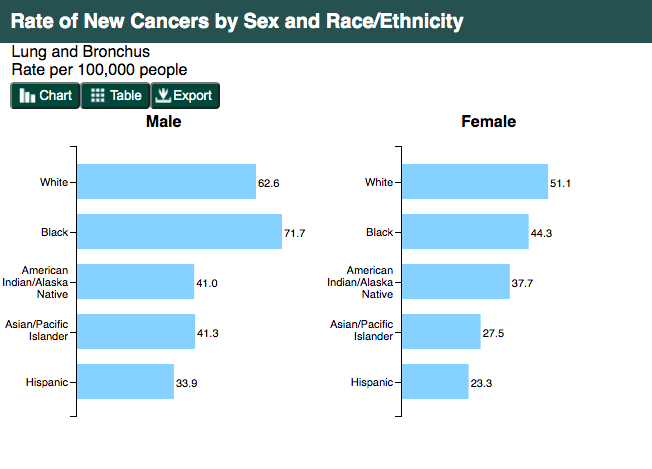

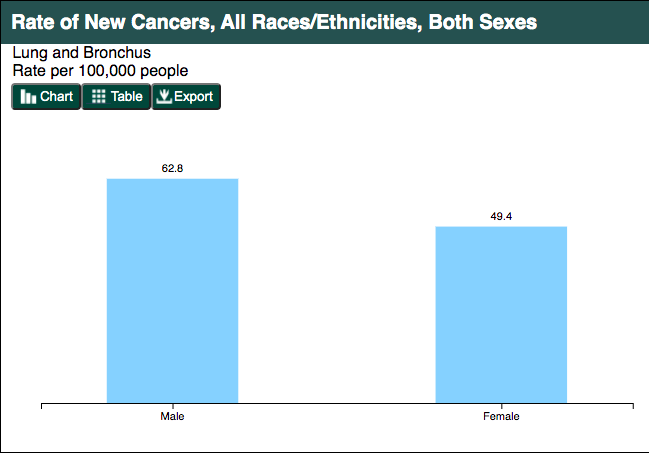

Most people with lung cancer do not show symptoms in the early stages but as the cancer advances, symptoms start to appear. They may seem small at first such as a cough that won’t go away, headaches, loss of voice, and fatigue (CDC, 2020). More extreme symptoms are chest pain, coughing up blood, shortness of breath, unintended weight loss, seizures, and vomiting (CDC, 2020). When diagnosing patients, there are two different types of lung cancer; small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Non-small cell lung cancer is further divided into adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (Collins et al., 2007). Non-small cell lung cancers account for 85% of lung cancer with small cell lung cancers accounting for 15% of lung cancers (Collins et al., 2007). Specifically, adenocarcinoma is the most common type of lung cancer compromising 38.5% of all lung cancers (Collins et al., 2007). The different lung cancer categories help doctors during diagnosis and treatment (Dela Cruz et al., 2011). African American men are the most susceptible to lung cancer compared to other ethnicities as the age-adjusted rate is 32% higher (Ryan, 2018). Hispanic men have the lowest incidence followed by American Indian/Alaska Native then Non-Hispanic White and African American men with the highest incidence (Ryan, 2018).

How Smoking Leads to Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is the most deadly form of cancer as the average five-year survival rate is around 15 percent (Collins et al., 2007). There are equal amounts of Americans that die of lung cancer compared to prostate, breast, and colon cancer combined (Collins et al., 2007). The most common cause of lung cancer is smoking as about 80-90% of lung cancer deaths are linked to cigarette smoking. This is mainly due to the fact that there are 70 known carcinogens in tobacco smoke. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2020), “people who smoke cigarettes are 15 to 30 times more likely to get lung cancer or die from lung cancer than people who do not smoke”. Men are especially at risk as they begin to smoke at an earlier age and for a longer duration than women (Visbal et al., 2004). Breathing in secondhand smoke from other people’s tobacco smoke also increases one’s risk for lung cancer. Occupational hazards such as radon, asbestos, arsenic, and diesel exhaust exposure increase one’s risk for lung cancer (CDC, 2020). These are common chemicals found in everyday activities such as cars, trucks, and houses that contain carcinogens which can lead to the formation of cancer when inhaled.

According to Collins et al. (2007), “the most important step in preventing lung cancer is smoking cessation”. Quitting smoking and prevention strategies have proven to be the most effective in decreasing lung cancer (Dela Cruz et al., 2011). The most effective types of quitting smoking treatments are nicotine replacement, counseling, social support, and other medications. Limiting any exposure to smoking such as never smoking, quitting, and avoiding secondhand smoke is very important to preventing lung cancer. Another preventative step is to take precautions to protect oneself from exposure to toxic chemicals at work and home such as asbestos and radon (American Lung Association, 2020).

Screening

Lung cancer screening remains a much debated topic as it has yet to prove that it decreases lung cancer deaths. Lung cancer screening has led to overdiagnosis, unnecessary anxiety, and high costs. There is not enough evidence to prove its overall effectiveness but it has shown to find early cases of lung cancer (Collins et al., 2007). The current guidelines for screening as supported by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) is annual low dose CT scans for patients aged 55 to 80 years old and with a 30 pack-year history (have smoked a pack of cigarettes a day for 30 years) or who have quit within the past 15 years (Latimer & Mott, 2015). The reason for the debate stems from the lack of knowledge regarding the long-term hazards from cumulative radiation exposure. There is a risk to be taken during the screening process and often times if lung cancer is found, it is difficult to treat. Due to the differences in guidelines and opinions, conversations with physicians and other health care workers must be had before considering lung cancer screening (Latimer & Mott, 2015).

Treatment

Treatment of lung cancer depends on the type of cancer, stage, and patient history. Overall staging of lung cancer is dependent upon the size of the tumor found and if it has spread to other organ systems. The smaller the tumor and less spread to other organs are reflected in a lower stage. Stage I is the lowest and stage IV is the highest and most severe. Stages I-III are considered local stages while stage IV and some aspects of stage III are considered advanced (Collins et al., 2007). The three most common types of lung cancer treatment consist of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Surgery is the primary treatment for patients with earlier stage lung cancer (stages I-III). Often times surgery will be followed up with rounds of chemotherapy and radiation based upon the progression of the cancer. For small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy and radiation are the most recommended treatments. For non small-cell lung cancer, minimally invasive surgery is recommended with chemotherapy and radiation to follow if needed. For the best outcome, a team of specialists including but not limited to a medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, pathologist, radiologist, and thoracic surgeon must be consulted related to lung cancer (Latimer & Mott, 2015).

Chapter Review Questions

1. What ethnicity is most susceptible to lung cancer compared to other ethnicities?

A. Hispanic

B. White

C. African American

D. American Indian/Alaska Native

2. Which of the following smoking cessation treatments has been found to be least effective?

A. Nicotine Replacement

B. Cold Turkey

C. Counseling and Social Support

D. Medication

3. What is the most common type of lung cancer?

A. Adenocarcinoma

B. Squamous Cell Carcinoma

C. Small Cell Lung Cancer

D. Large Cell Carcinoma

References

American Lung Association. (2020, April 2). How lungs work. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/how-lungs-work

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, September 22). Lung cancer: what are the risk factors. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/risk_factors.htm

Collins, L. G., Haines, C., Perkel, R., & Enck, R. E. (2007). Lung cancer: diagnosis and management. American Family Physician, 75(1), 56–63. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2007/0101/p56.html

Dela Cruz, C. S., Tanoue, L. T., & Matthay, R. A. (2011). Lung cancer: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 32(4), 605–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2011.09.001

Latimer, K. M., & Mott, T. F. (2015). Lung cancer: diagnosis, treatment principles, and screening. American Family Physician, 91(4), 250-256. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2015/0215/p250.html

Mayo Clinic. (2020, October 10). Lung cancer. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lung-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20374620

Ryan B. M. (2018). Lung cancer health disparities. Carcinogenesis, 39(6), 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgy047

Visbal, A. L., Williams, B. A., Nichols III, F. C., Marks, R. S., Jett, J. R., Aubry, M. C., Edell, E. S., Wampfler, J. A., Molina, J. R., & Yang, P. (2004). Gender differences in non–small-cell lung cancer survival: an analysis of 4,618 patients diagnosed between 1997 and 2002. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 78(1), 209-215. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.01.010