Elsa Meyer

Introduction

Prostate cancer occurs in the prostate gland of males. According to the American Cancer Society ([ACS] 2020d), prostate cancer is the second most common cancer for American men and about 1 in 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer. One in 41 men will die from prostate cancer, making it the second leading cancer that results in death for American men. Prostate cancer typically appears in men over the age of 65 (Rawla, 2019). Most prostate cancers grow slowly and don’t affect the male for years, but some grow quickly, metastasize, or result in death (ACS, 2020d).

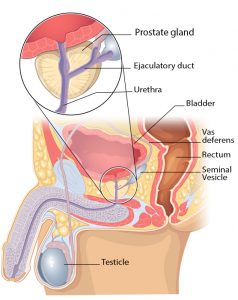

The prostate gland is a small gland that produces seminal fluid, which helps transport and provides energy to sperm. Sperm travels from the testes, through the prostate and penis, and out of the body (Prostate Cancer Foundation, n.d.).

Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention

The main cause of prostate cancer is unknown to scientists. However, there are various risk factors and doctors have an idea of how prostate cancer develops. Cancer is caused by a mutation of DNA, which is inherited or randomly occurs (2020b). Some of the risk factors mentioned below may potentially lead to random mutations that cause prostate cancer.

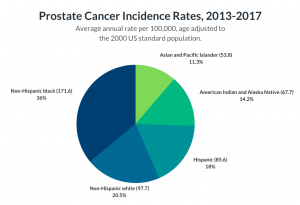

Risk factors for prostate cancer include old age, with the risk increasing at age 50 according to the Mayo Clinic (n.d.). Prostate cancer is seen more often in African-American men than any other race (ACS, 2020d). African-American men diagnosed with prostate cancer are also more likely to die from prostate cancer (Physician Data Query Screening [PDQ] and Prevention Editorial Board, 2019). More cases are seen in North America, Northwestern Europe, and Australia, and less often in Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. Some suggest this is due to higher testing and screening in these more developed areas (ACS, 2020a). Men with a family history of prostate cancer are at an increased risk, but the genetic link is unclear to scientists. Obesity is a potential risk factor and some studies have displayed a link to a higher risk of more aggressive forms of prostate cancer (ACS, 2020a; Mayo Clinic, n.d.). Other risk factors listed by the National Cancer Institute include hormones, vitamin E, folic acid, dairy, and calcium (PDQ Screening and Prevention Editorial Board, 2019). Risk factors stated by the American Cancer Society (2020a) also list smoking, chemical exposures, inflammation of the prostate, sexually transmitted infections, and vasectomies.

Because the cause of prostate cancer is largely unknown, prostate cancer prevention involves the body’s overall health. To reduce the risk of prostate cancer, the Mayo Clinic (n.d) recommends a healthy diet, frequent exercise, and maintaining a healthy weight.

Detection and Screening

Prostate cancer in the early stages doesn’t typically show symptoms, so a majority of cases are found through screening. More advanced prostate cancers show symptoms, including trouble urinating, a weak urinary stream, more frequent urinating, blood in the urine, blood in the semen, trouble getting an erection, bone pain, weakness in the legs or feet, loss of bladder or bowel control, and losing weight without trying (ACS, 2019c; Mayo Clinic, n.d.).

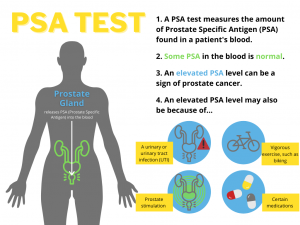

Men at average risk of prostate cancer should consider screening tests beginning at age 50 (ACS, 2019a). Rawla (2019) claims earlier screening “is highly recommended at age 45 for men with familial history and African-American men”. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level is tested to determine if there is an increased risk of prostate cancer. PSA levels can vary due to many factors, so it is often suggested to take another PSA test after a month if the initial PSA test showed abnormal results (ACS, 2019b).

Another screening test is the digital rectal exam (DRE), which is performed by the doctor inserting a finger into the rectum to inspect the prostate. The doctor feels for any irregular areas that may be bumpy or harder than normal. If these screening tests indicate the possibility of prostate cancer, a prostate biopsy is recommended. A biopsy takes a small sample of the prostate to be looked at under the microscope to determine if it is cancerous (ACS, 2019b).

Diagnosis and Treatment

Once a prostate biopsy is performed and cancer is found, the cancer is assigned a grade, called a Gleason score (ACS, 2019d). Two sections of the cancer are observed under a microscope and each given a score, with a lower score looking similar to healthy tissue. A higher Gleason score indicates more advanced prostate cancer (ACS, 2019d).

Prostate cancers often grow slowly and don’t pose significant, immediate health threats to the individual. Dr. Allaf (n.d.) from Johns Hopkins discusses active surveillance as an approach to these slow-growing cancers with a low risk of causing symptoms. Active surveillance could include a rectal exam and PSA test twice a year, a prostate biopsy once a year, or an MRI scan. Doctors recommend this option to cases that qualify to avoid the harsh side effects of treatment options that may harm the patient.

There are many treatment options for prostate cancer in more advanced stages. The type of treatment approach varies greatly between prostate cancer cases (ACS, 2020c). The American Cancer Society (2020c) lists surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and more. Treatment effectiveness is very different for each patient, and studies have shown a variety of results but conclude that active surveillance is increasing in popularity and effectiveness (Jayadevappa et al., 2017). The infographic included below provides a summary of prostate cancer and resources to learn more.

Chapter Review Questions

1. What is the main function of the prostate gland?

A. Holds urine

B. Produces sperm

C. Produces seminal fluid

D. Makes testosterone

2. The following are signs and symptoms of prostate cancer except:

A. Blood in the urine

B. Constipation

C. Trouble urinating

D. Loss of bladder control

3. What does a high PSA level in a person’s blood indicate?

A. Increased risk of prostate cancer

B. A urinary tract infection

C. Recent prostate stimulation

D. All of the above

References

Allaf, M. E. (n.d.). Prostate cancer: When to treat versus when to watch. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/prostate-cancer/prostate-cancer-treatment-what-to-know-about-active-surveillance

American Cancer Society. (2019a, August 1). American Cancer Society recommendations for prostate cancer early detection. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html

American Cancer Society. (2019b, August 1). Screening tests for prostate cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/tests.html

American Cancer Society. (2019c, August 1). Signs and symptoms of prostate cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html

American Cancer Society. (2019d, August 1). Tests to diagnose and stage prostate cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/how-diagnosed.html

American Cancer Society. (2020a, June 9). Prostate cancer risk factors. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

American Cancer Society. (2020b, June 9). What causes prostate cancer? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/what-causes.html

American Cancer Society. (2020c, June 11). Treating prostate cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/treating.html

American Cancer Society. (2020d, December 10). About prostate cancer.https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about.html

Jayadevappa, R., Chhatre, S., Wong, Y. N., Wittink, M. N., Cook, R., Morales, K. H., Vapiwala, N., Newman, D. K., Guzzo, T., Wein, A. J., Malkowicz, S. B., Lee, D. I., Schwartz, J. S., & Gallo, J. J. (2017, May). Comparative effectiveness of prostate cancer treatments for patient-centered outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA Compliant). Medicine, 96(18) e6790. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006790

Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Prostate cancer. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prostate-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20353087

Physician Data Query Screening and Prevention Editorial Board. (2019, April 10). Physician Data Query prostate cancer screening. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/patient/prostate-screening-pdq

Prostate Cancer Foundation. (n.d.) Prostate gland. https://www.pcf.org/about-prostate-cancer/what-is-prostate-cancer/prostate-gland/

Rawla, P. (2019). Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World Journal of Oncology, 10(2), 63–89. https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon1191

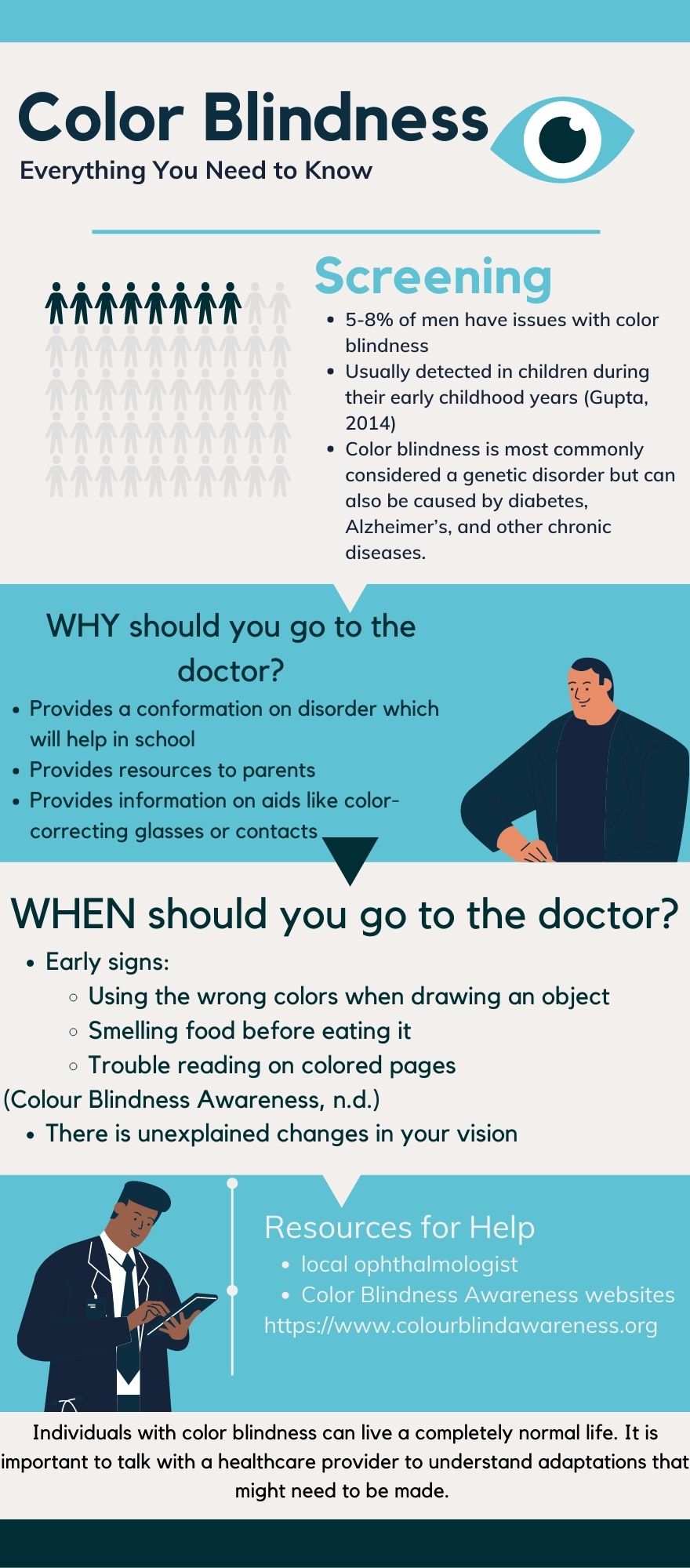

What is Color Blindness?

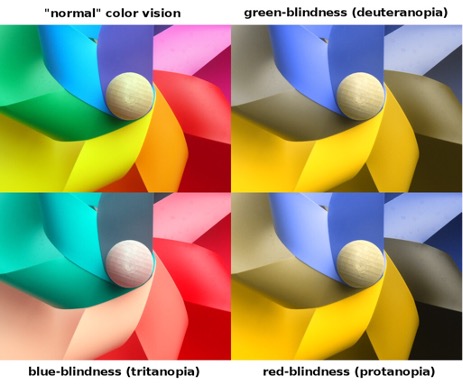

Color blindness is a disorder that makes it hard for individuals to see different colors. It might also cause people to not be able to see bright colors or different types of the same color. Color blindness occurs when there is an issue with how the eyes view colors. This is because the receptors in the eyes, called cones, do not work correctly. The most common type of color blindness is when it is hard to see differences between greens and reds. There are also cases when people cannot see differences between blues and yellow (National Institutes of Health: National Eye Institute, 2019).

Color Blindness Statistics

Color blindness most commonly affects males due to genetics. Genes are found on chromosomes and hold an individual DNA material. Males have an X and a Y chromosome while women have two X chromosomes. A male only needs to have an error in his X chromosome for there to be a development of a disease. In a female, they would have to have errors on both of their X chromosomes (Haldeman-Englert et al., n.d.). Five to eight percent of men in the world have issues with color vision while only one percent of females have issues with color vision (Melillo et al., 2017). If a mother has color blindness, the chances that her son also has color blindness is very high because the female passes the disorder on her X chromosome. In a study conducted, color blindness is most common in non-Hispanic white boys (5.6%) It is the least common for Black boys (1.4%) with Asian children (3.1%) and Hispanic children (2.6%) ranking in the middle (Xie et al., 2014).

Detection and Causes

Color blindness is usually detected in children during their early school years. It is not until children are learning the names of colors that color blindness is noticed (Gupta, 2014). Early signs of color blindness in school include using the wrong colors when drawing an object, smelling food before eating it, or trouble reading with colored pages (Colour Blindness Awareness, n.d.-a). Only an eye doctor (known as an opthalmologist) can determine if someone has the condition. However, here is an online screening tool if someone suspects he may be color blind.

https://www.eyeque.com/color-blind-test/test/

© 2021 EyeQue Corporation

Besides being born with color blindness, it can also be caused by other conditions like Alzheimer’s, and other chronic diseases. It is not uncommon for color blindness to get better once the inflicted disease gets managed or treated. Diabetes can cause color blindness because diabetes can cause damage to the back of the eye, where the cones in the eye are located (Kadrmas Eye Care New England, 2018). Alzheimer’s disease can cause issues with color blindness due to the eye’s inability to recognize or differentiate different colors. Color blindness can also be caused by aging and exposure to harmful chemicals later in life (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 2019). The video below explains how color blindness can affect an individual.

https://www.webmd.com/eye-health/video/what-colorblindness-looks-like

©2016, WebMD, LLC. All rights reserved

Living With Color Blindness

Depending on what part of the world a color-blind individual lives in, society views their condition differently. In the United Kingdom, color blindness is not considered a disability. In Japan, color blindness is a defect (Colour Blindness Awareness, n.d.-b). Japanese individuals with this condition are not allowed to perform certain jobs and sometimes are not even allowed to drive a car. In other countries, like the United States, color blindness is treated as a disability and must be addressed the same as other disabilities (Colour Blindness Awareness, n.d.-b).

In contrast, individuals with color blindness can live a completely normal life. Certain jobs might be more difficult for them. An electrician working with different colored wires would have difficulties if they were color blind (Colour Blindness Awareness, n.d.-b). While driving, an individual with color blindness might focus on the pattern of the stoplights rather than the colors. Instead of the green light meaning “go”, they would recognize that the bottom light means “go.” A color-blind individual might not be able to notice social cues of another person's mood changing due to the color of their face. They might not be able to notice their child being sunburnt or if their meat is cooked thoroughly. There have been instances where individuals have not been diagnosed with color blindness and then go on to not pass a vision test for their desired job. It can result in personal distress and sadness that could have been avoided if they were diagnosed earlier in life (Colour Blindness Awareness, n.d.-b). Research on this topic has been limited, therefore there is a small number of support options for these men. Color blindness awareness needs to be increased so that people with it can get the help and support that they need.

Management of Color Blindness

Currently, there are ways to help individuals with color blindness see colors. There are glasses and contact lenses that people can use that will help their eyes absorb colors correctly. The glasses and contact lenses are specific to what type of color blindness affects the individual. An individual with color blindness will not be cured with glasses or contact lenses but they will be able to see the different colors better than they did before (Salih et al., 2020).

The above infographic can help an individual through the process of determining if they might be color blind and what steps should be taken.

Chapter Review Questions

1. Why are men more likely to be color blind?

A. Women are exposed to color differentiation in daily life more often than men, so they have more practice

B. Men only have one X chromosome so if there is a gene for color blindness on the X, it will affect the individual

C. Men are more likely to perform risky behavior, therefore, increasing their risks of injury

D. Women do not have an X chromosome, so they are less likely to have the colorblind gene in their DNA.

2. What is the most common type of color blindness?

A. Red-green

B. Blue-yellow

C. Red-blue

D. No color- just black and white

3. What job will an individual with color blindness have the most difficulty performing successfully?

A. Truck driver

B. Electrician

C. Artist

D. Teacher

References

Ahlmann, J. (2011, September 14). Simulation of different color deficiencies, color blindness. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/entirelysubjective/6146852926

Colour Blind Awareness. (n.d.-a) Early symptoms. https://www.colourblindawareness.org/parents/early-symptoms/

Colour Blind Awareness. (n.d.-b) Living with colour vision deficiency. https://www.colourblindawareness.org/colour-blindness/living-with-colour-vision-deficiency/

EyeQue. (n.d.). Color blind test. https://www.eyeque.com/color-blind-test/test/

Gupta, R. C. (2014, August). Color blindness factsheet (for schools). KidsHealth from Nemours. https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/color-blind-factsheet.html?ref=search#cateyes

Haldeman-Englert, C., Freeborn, D., & Turley, R. K. (n.d.) X-linked inheritance: red-green color blindness, hemophilia. University of Rochester Medical Center. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?ContentTypeID=90&ContentID=P02164

Kadrmas Eye Care New England (2018, June 5). Alzheimer's & eyesight: Is there a connection? http://www.kadrmaseyecare.com/eye-health--care-blog/alzheimers-eye-sight-is-there-a-connection-alzheimers-brain-awareness-month

Martin, P. (2018, December 18). Curious kids: Why are people colour blind? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/curious-kids-why-are-people-colour-blind-107599

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2019, December 28). Color blindness. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/poor-color-vision/symptoms-causes/syc-20354988?utm_source=Google&utm_medium=abstract&utm_content=Color-blindness&utm_campaign=Knowledge-panel.

Melillo, P., Riccio, D., Di Perna, L., Sanniti Di Baja, G., De Nino, M., Rossi, S., Testa, F., Simonelli, F., & Frucci, M. (2017). Wearable improved vision system for color vision deficiency correction. IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine, 5, 1–7. 10.1109/JTEHM.2017.2679746

National Institutes of Health: National Eye Institute (2019, July 3). Color blindness. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/color-blindness

Salih, A. E., Elsherif, M., Ali, M., Vahdati, N., Yetisen, A. K., & Butt, H. (2020). Ophthalmic wearable devices for color blindness management. Advanced Materials Technologies, 5(8), 1901134. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201901134

WebMD. (2017, July 20). Colorblindness video: What color blindness looks like [Video]. https://www.webmd.com/eye-health/video/what-colorblindness-looks-like.

Xie, J. Z., Tarczy-Hornoch, K., Lin, J., Cotter, S. A., Torres, M., & Varma, R. (2014). Color vision deficiency in preschool children. Ophthalmology, 121(7), 1469-1474. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.018