Medieval (about 476AD-1600’s)

28 Leech Therapy in the Middle Ages

Emily Moersen

Introduction

The use of leech therapy in ancient Greece influenced and impacted the use of leeches into the Middle Ages, the early 19th century, and even modern times. In the Middle Ages, people began to look back and read Galen’s work and many physicians began to practice bloodletting using leeches again. The belief still stood that blood needed to be extracted to prevent it from becoming stagnant which caused disease and illness; Examples of this include Smallpox, the Plague, and Typhoid Fever which ran rampant throughout society, and most thought the only way to cure them was through bloodletting. It was also believed that the removal of fluids through leeches would cause a removal of a disease through organ heat, which was a more natural approach (Michalsen et al., 2007). The Middle Ages and the Medieval period were also a time of a religious revival where most of society was believing in witches, vampires, and a large amount of sin. They thought that sin resided in the blood, so in order to get rid of sin, they needed to get rid of their blood; therefore, in order to live a healthy, sin-free life, one must bleed out which was commonly accomplished by leeches.

Connection to STS

The discovery of medicinal leeches is a science, the application of this science for therapeutic use is a technology, and the combination of these ultimately affects society as a whole by providing a method of healthcare meant to heal certain individuals. This chapter was written to contribute to students’ understanding of STS as the chapter individually breaks down how Science, Technology, and Society are affected by leech therapy and describes how leech therapy relates to each component.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE LEECH

Leeches are annelid worms that can survive both aquatic and terrestrial environments, and they inhabit extreme environments related to temperature, moisture content, salinity, pressure, light exposure, and pollution. Due to their physiological flexibility, they are capable of inhabiting freshwater, estuaries, rivers, ponds, lakes, or sea (Abdualkader et al., 2013) where they locate their vertebrate hosts by sensing heat, chemicals or movement (Lemke & Vilcinskas 2020). These creatures contain suction-like features at both ends of their bodies and are most commonly known for being bloodsucking parasites. They typically pursue vertebrates such as humans, though they themselves are invertebrates with soft bodies lacking a skeleton, and, though their bites may cause discomfort, they are typically not harmful; it is the components of the leech’s saliva, rather, that can cause extensive bleeding, even long after the leech is removed from the skin. Leech saliva acts as an anticoagulant, meaning it prevents the blood from clotting properly. They grip onto the skin of a human with hundreds of their sharp and calcified teeth making an incision with which they then suck on the pooled blood. Leeches aim to remain attached to their host until they increase their body weight by eleven times its weight prior to feeding, and it can take several months for the leech to digest the human blood. The leeches then secrete their infamous saliva containing proteolytic enzymes that increase the permeability of human skin, dilate blood vessels, and inhibit inflammatory response (Phillips et al., 2020).

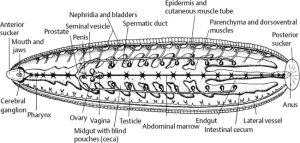

The leech has one small anterior sucker which surrounds its pointed, apical mouth, and the anus opens on the dorsal surface above the other large, rear sucker. Leeches also have two additional types of excretory organs consisting of the nephridia (male) and hermaphrodite (female) reproductive organs. Many may wonder from which sucker the leech breathes; however, surprisingly enough, respiration actually takes place through the walls of the body. Leeches also consist of thirty-four segments in which the last seven of them form the large rear sucker and 105 external rings called “annuli” that stretch similarly to an accordion. Each segment is covered by up to five annuli which assists in the leech’s locomotive activity (Themes, 2016). Most leech species range from 20-50 cm in length (Abdualkader et al., 2013).

These blood-letting creatures have a double-walled “digestive tube” that consists of the foregut, midgut (stomach), and hindgut. These three organs occupy the largest volume of tissues in the body of the leech. The foregut, comprising the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus, makes up approximately two tenths of the entire length of the animal. The stomach, which consists of ten pairs of blind pouches, makes up roughly five tenths of the total length. The hindgut makes up the remaining three tenths of the total length. The leech stomach serves as an enormous storage chamber that enables the leech to survive up to several years without food. Even after the stomach contents have been fully depleted, the leech can survive for months gathering nutrients from its own body substance.

Lastly, it is important to note that leeches have very developed neurological function which is crucial to their effectiveness as hunters and predators (Themes, 2016).

use of Leech Therapy as a Medicinal Practice

Leeches were a simple and cheap method of curing diseases in which a person contained too much blood. This was, therefore, very appealing to medievalists. The most well-known leech used in hirudotherapy, in other words, the medicinal practice of leeches, is Hirudo medicinalis because its saliva contains at least thirty individual chemicals with the best anticoagulant properties as compared to other leech species (Phillips et al., 2020). H. medicinalis is placed on various spots of the body’s surface, and, because of this, it can be extremely difficult for the host to brush the leeches off in addition to the intense attachment method of the leech (Themes, 2016).

Ancient Egyptian, Indian, Greek, and Arab physicians used leeches for a wide range of diseases such as the conventional use for bleeding to systemic ailments including skin diseases, nervous system abnormalities, urinary and reproductive system problems, inflammation, and dental problems (Abdualkader et al., 2013).

Execution of Leech Therapy in Medieval History

In the 19th century, leeches (Euhirudinea) were employed to treat issues such as mental disorders, skin diseases, gout, headache/migraines, arthritis, and whooping cough. They were first named by Linnaeus in 1758 AD and are related to the phylum Annelida and class Clitellata (Abdualkader et al., 2013). The practice of leech therapy gained its immense popularity in the 19th century and, after its spread to Europe, later became known as “vampirism.” At that time in history, leeches were returned after use to the nearby ponds in which they were found because there was no fear of transferring diseases through microorganisms. This is because scientists had not yet discovered microbial species. Leeching became such a popular and lucrative business that people began shipping them to other countries such as France, America, Australia, and England which, therefore, began a depletion in the number of available leeches for medicinal practice. With this being said, the earliest clearly documented record of leeches being used for medicinal purpose appears in a painting found in an Egyptian Tomb from around 1500 B.C. (Younis et al., 2008). Early taxonomists identified 696 species of leeches but, recently, more than 1000 leech species have been identified (Abdualkader et al., 2013).

Consideration of Leech Therapy in Modern-Day Medicine

Leeching has made a comeback in the 20th century as a new remedy for many chronic and life-threatening abnormalities, such as cardiovascular problems, cancer, metastasis, and infectious diseases. The leeches used in modern medical practice are mostly imported from Turkey and Bulgaria (Hohmann et al., 2018). Many therapists use leeches for the healing of hypertension, varicose veins, hemorrhoids, gonarthritis, and secondary ischemia-related dermatosis. Despite the proven-effective properties of medicinal leech therapy, the safety and complications of leeching are still controversial between researchers (Abdualkader et al., 2013).

According to The Biology of Leeches, the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) officially approved the leech as a “medical device” based on scientific evidence of the efficacy of leeching in specific diseases on July 24, 2004. In one particular circumstance, research showed the act of leeching highly improved osteoarthritis of the knee in many patients. Most recent, modern-day leeching has been limited to being used only in microsurgeries to relieve venous congestion and and plastic surgeries for cosmetic purposes because it was later found by researchers that using these creatures as symbiotic assistants is more harmful to leeches than beneficial (Younis et al., 2008). Not only the active blood drainage that results from the leech sucking action motivated medics to use leech to alleviate venous congestion, but also the passive oozing after leech detachment due to the presence of the long-acting anticoagulants in leech saliva. The relieving effect is the accumulated result of the leech bite-induced blood oozing, which is a consequence of many factors, including bleeding wound, secreted bioactive enzyme, anticoagulants, and vasodilators.

Research also found the use of leeching to prevent certain cancers. Ghilanten, an antimetastatic and anticoagulant protein, was purified from the salivary gland secretion of the proboscis leech and was reported to suppress metastasis of melanoma, breast cancer, lung cancer, and prostate cancer. Another research described a synthetic hirudin preparation as an efficacious metastasis inhibitor of a wide range of malignant tumor cells, such as pulmonary carcinoma, breast carcinoma, bladder carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, soft-tissue sarcoma, leukemia, and lymphoma. By the year 2010, other scientists discovered that a two month treatment by topical application of H. medicinalis could completely cure the local lumbar pain in patients with advanced stages of renal cancer and leiomyosarcoma.

Leeching is currently being considered for other applications such as dentistry abnormalities such as tongue swelling, audiology abnormalities such as hearing loss, and skin disorders like shingles (Abdualkader et al., 2013).

Missing Voices

Now that the process of leech therapy has been throughly described, it is important to highlight the impact it has had on specific individuals. The voices of those who have experienced medicinal leeching are typically overlooked. Attached below is a video containing the perspective of a modern-day, Arizona native who consistently receives the therapy to relieve her of detrimental migraines.

ConCLUSION

Leech therapy emerged as a prominent and widely-practiced medical treatment in the Medieval period, and its desirability has allowed it to greatly influence the development of modern medicine. Medicinal leeches were used by Egyptian, Indian, Greek and Arab physicians thousands of years ago. The main application was bloodletting, but leeches were also recommended for the treatment of systemic ailments such as inflammation, skin diseases, rheumatic pain or problems with the reproductive system. As an advocate of leech therapy, Galen, the Greek physician of Pergamon (130–201 AD), described leeches as an effective treatment for numerous diseases. Later, in the Middle Ages, leech therapy was popular because it was less painful than conventional treatments and was recommended even for diseases of the nervous system and eyes (Lemke & Vilcinskas 2020). Bloodletting, therefore, was one of the most influential factors regarding medicine in the history of the Medieval times.

Chapter Questions

- Multiple Choice: Why did medieval physicians believe in the effectiveness of leech therapy?

a. To ward off evil spirits

b. To extract toxins from the body

c. To test a patient’s bravery

d. To improve vision - Short Answer: What was leech therapy, and how did it work in medieval times?

-

True/False: Leeches have sharp teeth which promote excessive bleeding.

REFERENCES

Abdualkader, A. M., Ghawi, A. M., Alaama, M., Awang, M., & Merzouk, A. (2013, March). Leech therapeutic applications. Indian journal of pharmaceutical sciences. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3757849/

Hohmann, C.-D., Stange, R., Steckhan, N., Robens, S., Ostermann, T., Paetow, A., & Michalsen, A. (2018, November 23). The effectiveness of leech therapy in chronic low back pain. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6334223/

Lemke, S. & Vilcinskas, A. (2020, April 27). European medicinal leeches-new roles in modern medicine. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9059/8/5/99

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Plague definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/plague

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Smallpox definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/smallpox

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.-c). Symbiotic definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/symbiotic

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Typhoid fever definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster.

https://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/typhoid%20fever#:~:text=food%20or

%20water-,Medical%20Definition,typhi)

Michalsen, A., Deuse, U., Esch, T., Dobos, G., & Moebus, S. (2001, October). Effect of leeches therapy (Hirudo medicinalis) in painful osteoarthritis of the knee: A pilot study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1753399/

Phillips, A. J., Govedich, F. R., & Moser, W. E. (2020, September 19). Leeches in the extreme: Morphological, physiological, and behavioral adaptations to inhospitable habitats. International journal for parasitology. Parasites and wildlife. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7569739/

Themes, U. (2016, October 3). The Biology of Leeches. Musculoskeletal Key.

https://musculoskeletalkey.com/the-biology-of-leeches/

Younis, M. Irfat, A., Huma R., Zahoor A. (2008, July 1). Leeching in the history–A Review. Pakistan journal of biological sciences : PJBS. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18819614/

MEDIA CITED

Arizona leech therapy helps a valley woman get relief from migraines and other ailments. YouTube. (2018, March 21). https://youtu.be/d7qxsiPfqRg?si=lD1OuJht3EJkg-Q7

National Library of Medicine/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY. (n.d.). Bloodletting, leech method – stock image – C033/4146. Science Photo Library. https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/813651/view/bloodletting-leech-method

Says:, J., & Says:, S. (2022, July 26). How medieval medicine is helping us today. Just History Posts. https://justhistoryposts.com/2017/02/25/how-medieval-medicine-is-helping-us-today/

Themes, U. (2016, October 3). The Biology of Leeches. Musculoskeletal Key.

https://musculoskeletalkey.com/the-biology-of-leeches/

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) use disclosure

I used ChatGPT to help me find information about Leech Therapy in the Medieval period that suits the goals of this textbook chapter.

Chatgpt. ChatGPT. (n.d.). https://openai.com/chatgpt