Mental Health

120 Psychological Priming

Brian Dinnell and River Young

Introduction:

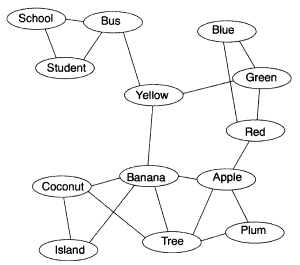

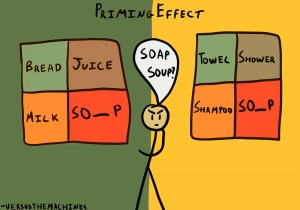

Priming is the idea that exposure to one stimulus may influence a response to a subsequent stimulus, without conscious guidance or intention. This phenomenon reveals the intricate ways in which our minds process information, as seemingly unrelated cues can subtly influence our perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Through various experiments, researchers have uncovered some of the reasons on how priming works. As a captivating facet of cognitive psychology, priming sheds light on the intricate interplay between external stimuli and the intricate workings of the human mind.

Karl Lashley, a pioneering figure in psychology and neuroscience, is not directly associated with the concept of priming in the traditional sense. Lashley’s influential work primarily focused on understanding brain function, particularly in the realms of learning and memory. His renowned studies involved lesioning specific areas of the brain in rats to investigate memory localization, ultimately leading to the formulation of the concepts of “mass action” and “equipotentiality.” While Lashley’s research did not explicitly delve into the phenomenon of priming as understood in contemporary psychology, his foundational contributions laid the groundwork for later investigations into how external stimuli, like those explored in priming experiments, can influence cognitive processes. The principles derived from Lashley’s work contributed to the broader understanding of how the brain processes and stores information, providing a backdrop for the exploration of related concepts, including priming, in subsequent psychological research.

Experiments

Researchers wanted to find out if emotions and emotion-laden word processing differed. An experiment was run on undergraduate students from Albany State University to try and find out. The procedure for this experiment was that subjects were to stare at a cross in the middle of a screen, then a priming word would be flashed for 250 milliseconds , then the target word would be shown and the subjects were given 2000 milliseconds to respond. The subjects had to press a key if the target word was an actual word or another key if it was a nonword. First, the researchers found that response time was faster when the words were related than when they were not. Then the researchers found that emotion positive words that were related(example: passion-love)had a faster response time than emotion negative words that were related(example: blackmail-tomb). The researchers found that the effect of emotion priming was larger than emotion-laden priming. Another experiment was run with different students from Albany State University. This experiment flashed a priming word for 50 milliseconds followed by ######### for 200 milliseconds and then finally the target word where the student had 2000 milliseconds to respond. This second trial was used so that the subject could see but didn’t explicitly process the priming word. The researchers found that again the response time was faster when the words were related than when they were not. They also found that there was a shorter response time when there were emotion targets versus when there were emotion-laden targets. They also found that again emotion positive words that were related (example: passion-love) had a faster response time than emotion negative words that were related (example: blackmail-tomb).

Findings:

Both studies found that people can be influenced solely by seeing words. By seeing a word for a fraction of a second, people’s response time would change. When the priming word was related to the target word it was found that people’s response time was faster than when the priming word was not related. They also found that the more positive words also caused people to have a faster reaction time than when negative words were used.

connection to STS

The connection between priming and Science, Technology, and Society (STS) is significant when examining how technological systems embed and exploit our psyche. In the digital age, algorithms on social media platforms use forms of priming by curating content that is likely to prime users emotional responses, often leading to greater engagement or polarization. Similarly, search engines and recommendation systems subtly prime users perceptions by selectively presenting information. This interaction between technology and cognitive science highlights a major STS concern: how scientific knowledge about human behavior is used in the construction of technological systems that, in turn, shape societal values and individual cognition. Understanding priming allows STS scholars to critically assess not only technological impacts but also the ethical responsibilities of those who design such systems (Fuchs, 2014).

Applications of Priming in Everyday Life

Priming is not just a laboratory phenomenon; it has real world applications that subtly influence our daily lives. In advertising, marketers often use positive imagery and emotionally charged words to prime consumers to feel favorable toward a product without them even realizing it. Politicians also use priming when crafting speeches, subtly linking certain words or ideas to emotional responses. Priming can even be found in education, where positive reinforcement primes students to feel more confident in their abilities. In the legal field, lawyers may strategically prime jurors by using emotionally loaded language during opening statements. Understanding how priming works outside of experiments shows just how much of human behavior can be shaped by hidden cues in our environments.

Neurological Mechanisms Behind Priming

Scientists have been interested in what happens inside the brain during priming. Research using brain imaging techniques such as functional MRI (fMRI) has shown that priming activates certain neural pathways more efficiently. When a primed stimulus is encountered, the brain does not have to work as hard to recognize or respond to it, leading to faster reaction times. Specific areas like the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus play major roles in processing primed information. This neural efficiency also explains why positive emotional primes often have stronger effects because they engage reward circuits in the brain. As research in cognitive neuroscience advances, our understanding of these underlying processes continues to deepen, offering new insights into the mechanics of human thought and perception (Meyer & Schvaneveldt, 1971).

Ethical Concerns of Priming and Manipulation

With the power of priming comes the potential for unethical manipulation. Media outlets, corporations, and political groups can exploit priming to influence public opinion or consumer behavior without people’s awareness. Subliminal messages, although controversial, are a form of priming intended to subtly influence emotions or decisions. There is ongoing debate about whether using priming techniques without informed consent crosses ethical boundaries. Psychologists argue that while priming can have positive applications, such as encouraging healthy behaviors, it must be used responsibly. Awareness of how priming affects cognition helps people critically evaluate the stimuli they encounter daily, encouraging more mindful decision-making (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999).

Chapter Questions

- Multiple Choice: Which of the following best describes a real-world application of psychological priming?

A) Using punishment to change behavior

B) Repeating instructions to improve memory

C) Flashing positive words in advertisements to influence consumer feelings

D) Giving immediate feedback after a task - Short Answer: What are two ethical concerns that arise from the use of priming in media and technology?

(Hint: Think about manipulation and awareness.) - Short Answer: How does priming connect to the field of Science, Technology, and Society (STS)?

references

Purcell, D. G., & Stewart, A. L. (2016). Reacting to Emotion: Anger Arrests and Happiness Helps. The American Journal of Psychology, 129(4), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.129.4.0363

Cosimo Marco Scarcelli. (2015). Christian Fuchs, Social Media. A Critical Introduction, Sage, 2014. Tecnoscienza (Padua, Italy), 6(1), 166–169. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2038-3460/17249

Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (1999). The Unbearable Automaticity of Being. The American Psychologist, 54(7), 462–479. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.462

Meyer, D. E., & Schvaneveldt, R. W. (1971). Facilitation in recognizing pairs of words: Evidence of a dependence between retrieval operations. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 90(2), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031564

Image Credit

Marketing Society. (n.d.). [Image of blue circles from the Marketing Society website]. https://www.marketingsociety.com/sites/default/files/circles.png

The Decision Lab. (n.d.). Priming. https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/priming

AI Acknowldegment

I acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (https://chat.openai.com) to assist in editing, revising, and updating this chapter. The prompts used included “Mark any grammar/ structure errors in the following text [original text pasted],” “Create an outline that could be used to complete this chapter entry into a textbook [original text pasted, rubric image inserted],” “Create proper APA citations for the following sources,” “How can priming be used in a bad way.” The output from these prompts was used to enhance clarity, brainstorm new ideas, and create proper APA citations.