Medieval (about 476AD-1600’s)

17 Technological Developments in the Mongol Empire

Alayna Williamson

Introduction:

The Mongol Empire originated with Temujin, later known as Genghis Khan. His father Yesugei, a Mongol military leader, kidnapped his mother Ho’elum from her bridegroom in the Olqunu’ud clan, sparking a feud. At 15, Temujin was betrothed to Borte from the Onggirad tribe staged by Yesugei who was poisoned by the Tatars upon is return. Temujin’s family was abandoned by their tribe, leading to their starvation and his murder of his older brother Bekhter. Temujin was captured by the Tayichi’u, who sought revenge and punishment for Bekhter’s death, but escaped with the help of the Sorqan Shira household.

He gained his first follower, Bo’orchu, and sought support from Toghril Khan to rescue his betrothed, Borte, from the Merkit tribe. Through Toghril, he befriended Jamuqa to learn warfare, but when Temujin became khan of the Borjigid Mongols, Jamuqa attacked and forced him to flee to the Jin Empire. After nearly a decade, Temujin returned stronger, with many Mongols deserting Jamuqa due to his cruelty. His power continually surged as he defeated the Tayichi’ud.

In addition, Temujin demolished the Tatars with Toghril and received one of his many titles from the Jin. Toghril eventually turned against Temujin, leading to a battle where the he was conquered. Temujin captured Jamuqa in 1204-1205; during a battle on Chakirmaut on the slopes of Khangai Mountains, Temujin used incredibly effective tactics. According to the book “The Mongol Empire”, “Here he displayed a military genius in terms of organization, discipline, tactics and strategies that completely baffled his enemy, including opponents like Jamuqa who were well-regarded military leaders and familiar with Temujin’s style of warfare.” (May, 2018).

In 1206, Temujin was titled Chinggis Khan and reorganized society into a military system, uniting the Mongols. He established a bodyguard unit and trained his staff in military and administrative roles.

For political background, the Mongol political structure consisted of a Kurultai and a Great Khan. The Kurultai was a council made up of Mongolian nobles that held both political and military authority and was responsible for appointing the Great Khan. Genghis Khan was the first to be granted this title in 1206. Following the division of the empire into four Khanates, Yuan, Ilkhanate, Golden Horde, and Chagatai, the position of an official Great Khan ceased to exist, although the khans of the Yuan Khanate continued to use the title.

Connection to STS:

The Mongol Empire as a whole has several connections to our science, technology, and society class. The developments the empire faced over its reign included scientific discoveries, creation of technologies, and societal contributions. All of this shaped how the Mongol Empire and Genghis Khan is remembered.

Military Innovation:

Military innovation was revolutionary during the reign of Genghis Khan in the Mongol Empire. He won pivotal battles using his distinct military scare tactics. His soldiers were heavily trained in siege warfare and other techniques. Mongolian technology and military strategies were key to their success in this.

Stirrups:

Saddles and stirrups were essential to mounded archers who traveled and fought in the Mongol Empire. They had wooden saddles and sturdy paired stirrups. It is likely, due to nomadic tradition, that men crafted these wooden saddles and metal (probably iron) stirrups; they were first paired in the early first millennium CE in the region of the Xiongnu confederation that the Mongols later descended from. Mongols had similar technology to other regions and nomadic groups, such as the Huns, who did not come close to achieving the same military success. This proves that leadership and politics within the Mongol empire were distinctive.

Bows:

The Xiongnu significantly influenced Mongol archery with their innovations. They developed two types of bows: a light bow for mounted archery and a heavier bow for long-range ground shots. Different quivers held arrows for various purposes—close-range, armor-piercing, and long-distance shots. Recurved and reflexed composite bows stored more energy and provided greater force and velocity, making them highly efficient on horseback. The unstrung reflexed bow had limbs of the bow reverse themselves away from the direction of the draw; the strung recurve bow had limbs bent forward and away from the archer. The asymmetric feature of this bow allowed archers to aim effectively from either side of their horse.

Only two complete Mongol conquest-period bows have been found, one in a cave at Tsagaan Khand in 2010, and the Omnogovi Bow discovered in a cave burial in 1984. This was due to the dryness of the cave that allowed for preservation. Like all Mongol bows, this one found unlike lacked stiffening bone plates that the Huns used which enhanced their effectiveness.

Gunpowder / Siege :

Genghis Khan’s siege warfare involved missile engines mounted on animals or wagons, and utilized Chinese engineers, weapons, and technology. This method was used to breach walls and destroy cities. As the Mongols advanced toward Northern China, they shifted from quick attacks to slower siege tactics, which required building dams, diverting rivers, or constructing large earth ramparts, often involving thousands of laborers. John Plano Carpini, an emissary of Pope Innocent IV, states, “…they fence around a fortress, make strong attacks with engines and arrows, not stop day or night, if a city has a river – they dam it or alter course and submerge fortress if possible. If not, armed men enter from underground, start fires”. (Raphael, 2009).

Up to the rule of Hulegu, Genghis Khan’s grandson, siege warfare continued to evolve using manually powered Chinese siege machines including Pao catapults, large crossbows, and vessels with inflammable materials producing toxic fumes. They contained pots with wicks of flax cotton that contained the basic ingredients of gunpowder. An example of this was when Chinggis Khan destroyed the city of Bukhara; the entire town was set on fire with exception of the Friday mosque and some palaces. During the Siege of Nishapur in 1221, the Mongols employed thousands of siege machines, crossbows, and other equipment. Engineering teams, capable of planning large-scale projects, played a crucial role, operating 24/7.

Infrastructure and Communication:

The Mongols extended the Grand Canal to Beijing, built Daidu as their capital, and constructed a summer palaces in Shangdu. Khubilai Khan and his successors employed Confucian scholars and Tibetan Buddhist monks, leading to new temples and monasteries as well.

Yam System:

The Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous land empire in history, needed efficient communication across its territory. They established a postal system called the “Ortoo” with stations every 20 to 30 miles, allowing riders to pass messages quickly. It allowed riders a space to sleep, eat, and feed their horses. Initially, merchants and travelers could use this system, but abuses led to revoking the privilege. Fast communication networks were crucial for security and political awareness for all nations. Inspired by Chinese systems that provided messengers “yamci” or “ulakci”, the Mongol postal service had stations equipped with 20 horses and messengers. Ogeday Khan and his brother Chagatai Khan, the sons of Genghis Khan, enhanced the system with 37 stations between Karakoram and China, each staffed with 1000 soldiers and supplies.

A convention in 1240 introduced rules to ensure new efficient message delivery, including avoiding cities and establishing stations. Annual inspections of quality and penalties maintained order as disobedience and deficiency was reported to the Khan.

Marco Polo, quoted by S. Egilmez and G. Bayram Kalkan in “Yam (Post/Communication) Organization in Mongols” describes it, “These are nice and broad constructions which were beautifully furnished and walls covered with silk with many rooms and they could meet the needs of important people. Four hundred high quality breed horses are always ready as the messengers and envoys of khanate could change their horses anytime when they come…This makes evident that the Great Khan is bigger and stronger than the other rulers and kings” (Marco Polo, 2017: 98-99)

Downfall of the Yam System:

However, abuses by foreign ambassadors and merchants still led to the system’s decline despite reforms. Hulagu Khan’s even introduced tax exemptions and reformed tax systems to support the network, but misuse persisted. Couriers often bypassed stations on the itinerary and instead plundered prosperous areas and which burdened the public. Also, lack of utilizing main roads for travel caused the arrival of news to reach later to the concerned persons. Ilkhanid emperor Gazan Khan attempted restricting anyone other than officials with “yarling” or “gold tamga” from benefit from the stations, but failed as roads still fell into disrepair. The system regained some function in the Yuan Khanate as it did in the Ilkhanids until the empire’s decline in 1320. In the end, it fully strayed away from its main purpose and filled the system with disarray.

The Silk Road:

The Mongols also developed a network of roads, aiding scientific and engineering progress. The infrastructure supported European merchants traveling to China, fueling the Age of Exploration and increased European demand for Asian goods. The Silk Road, a network of trade routes, significantly impacted both the East and West. This extensive trade network connecting South-East Asia, Japan, Europe, and eastern Africa, facilitated the exchange of goods like gunpowder, paper, bills of exchange, and banking innovations. It also enabled globalization, with luxury goods such as silk, furs, spices, and tools like pots and iron needles. Muslims joined the Mongol empire as merchants, and metals like silver were transported from Burma to Europe due to depleted European mines. It also spread diseases like the Black Death via fleas transported by caravans.

Cultural and Intellectual Exchange

Silk Road Cultural Exchange:

The Mongols promoted travel and innovation along the Silk Road, encouraged European artists, and were hospitable to foreign travelers. Genghis Khan implemented religious freedom, enhancing security and unity, as outlined in the Yassa, which respected all religions. The Code of Law in the Yassa according to De Graaf in 2018 states that,” ‘He ordered that all religions were to be respected and that no preference was to be shown to any of them. All this he commanded in order that it might be agreeable to God’ ” (Great Yasa of Chinggis Khan, 2010). This allowed the spread of various faiths, including Buddhism and Nestorian Christianity, throughout the empire. Leaders were of all different faiths; for example, Genghis Khan practiced Shamanism, but his sons married Christian wives. Also, several advisors has different faiths like Mahmud Yalavach who was a governor who practiced Islam.

Relocation of Skilled Artisans:

Skilled artisans and astronomers migrated to centers of learning like the Maragha observatory, fostering the exchange of astronomical knowledge. Notable scholars included Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi and Chinese Daoist scholar Fu Mengzhi. The Mongols adopted elements from neighboring cultures, such as Persia and ancient China. For instance, Mongols in China who converted to Buddhism adopted the Tibetan calendar.

Scientific Contributions:

Astronomy:

The Mongols’ keen interest in astronomy led to significant developments. Kitan astronomer Yelu Chucai worked with Muslim and Chinese astronomers under Genghis Khan. His successor, Mongke, prioritized the creation of an observatory built by Muslim astronomers. In the Ilkhanate, Hulegu constructed the Maragha observatory in 1259, attracting diverse astronomers, including Nasir al-Din al-Tusi. Ghazan later founded an observatory in Tabriz based on the Maragha, where Persian and Arabic astronomical works were translated into Greek. The Ilkhanid astronomers, some prompted by promise of social mobility, greatly contributed to the spread of astronomical knowledge.

In Yuan China, the Muslim Directorate of Astronomy was established in 1271, merging with the Chinese Directorate of Astronomy to form a large agency under the direction of the Palace Library. Students from there were educated and prepared for The Astrological Commission that was founded in 1278; it was its own large autonomous government agency. In total, there were 265 experts, clerks, and students total that were involved in the bureaus for astronomy. Zhao Youqin, a prominent Daoist hermit, advanced new astronomical theories and instruments. He developed new theories and instruments in his treatise “New Writing on the Symbol of Alteration”.

Astronomical innovation flourished in both the Ilkhanid and Yuan empires, with a notable exchange of knowledge and expertise among diverse scholars. Examples of prominent scholars, as mentioned, were Yelu Chucai, Nasir, and Zhao Youqin.

Medicine:

Due to Mongol demand, Chinese surgeons specialized in orthopedics, using opium as anesthesia and the suspension method of joint reduction. Prominent Chinese surgeon Wei Yilin was one of those employed to write about this knowledge. It spread from East to West, largely influencing surgical practices beyond the Mongol reign – such as those in Europe. Pax Mongolia, the century of peace and stability, facilitated the European Renaissance and the rise of modern medicine. Prominent medical figures like Rashid al-Din and Mansur Ibn Ilyas contributed significantly to surgical science, impacting early medical schools in Europe such as the one in Oxford.

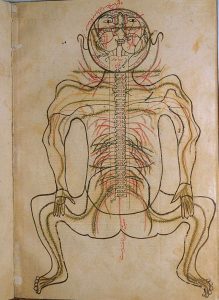

The connectivity on the Silk Road lead to the establishment of hospitals based on Persian models and collaborative medical teams of diverse ethnicities. Rashid al-Din founded the Rabi Rashidi institution in Tabriz, which published the first manuscript on Chinese surgery outside China. The institution contained a research hospital, medical school, and library containing 60,000 texts. Mansur Ibn Ilyas created the world’s first color atlas of human anatomy in 1386, used in European medical schools of the 14th century. It accurately details the anatomy of the optic nerves and their functions as well as some arterial and skeletal systems.

In 1263, the Medical Bureau of the Capital was established in Beijing, ensuring the representation of European and Islamic practices. Fractures and dislocations were treated by a ‘Bariachi’ who were specialist bonesetters working in a separate field from physicians.

Conclusion: Fall of Empire

After Ogedei Khan’s death, his widow ruled the Mongol Empire, persecuting some officials and promoting allies to secure her son Guyuk’s succession. Batu, Khan of the Golden Horde, refused to attend the Kurultai, causing a power vacuum until 1246. Guyuk was later elected but died in 1248, leading to further power struggles. Batu nominated Mongke, Genghis Khan’s grandson, who died during a campaign in China from a disease outbreak. His brother Ariqboke took the throne, but Kublai Khan contested, leading to civil war. Kublai eventually became Great Khan, but the empire fragmented over time, with each khanate becoming more independent.

Pax Mongolica, a 100 year period of peace, allowed safe trade along the Silk Road, but tensions rose in 1350 due to religious and territorial disputes. The Yuan dynasty’s favoritism towards Buddhism caused uprisings like the Ispah Rebellion. Here, Sunni Muslims were financially assisted by Mongols as they became more politically and economically influential. This lead to an uprising of Shia Muslims who were eventually massacred by Yuan commander Chen Youding. Native Chinese citizens resented Mongol rule as Kublai Khan began to stress Mongol identity, leading to the Ming dynasty’s rise in 1368. This allowed native Chinese people to regain control and all foreign influences, such as trading with the khanates, was removed.

The Golden Horde experienced civil wars and external attacks, weakening its power as well. It was defeated in 1396 and lost all territory as provinces broke away. The Bubonic Plague further destabilized the empire, leading to its gradual decline in the 14th century. Revolts due to plague and tensions cut production of goods and flow of trade which contributed to its eventual collapse.

Chapter Questions:

- Why did the Yam System collapse in the Mongol Empire

A) Genghis Khan destroyed them

B) Merchants and travelers exploited them

C) The different cities rejected the spread of information to the Khan

D) No one used or desired to use the system

2. Who contributed to the construction of the Maragha observatory?

A) Kublai Khan

B) Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

C) Ghazan

D) Hulegu

References:

De Graaf, W. (2018). THE SILK ROAD IN THE MONGOL ERA THE SILK ROAD IN THE MONGOL ERA. https://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=146210

EGILMEZ, S., & BAYRAM KALKAN, G. (2023). Yam (Post/Communication) Organization in Mongols. Turcology Research, 77(1), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.5152/jtri.2023.23196

Köstenbauer, J. (2017). Surgical wisdom and Genghis Khan’sPax Mongolica. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 87(3), 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.13813

May, T. M. (2018). The Mongol empire. Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474417402

Mongols in world history: Asia for educators. Mongols in World History | Asia for Educators. (2024). https://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/history/history_a.htm

Mongol Empire: Special Features – History. (2017, May 11). History. https://www.historyonthenet.com/mongol-empire-special-features

One Bow (or Stirrup) Is Not Equal to Another: A Comparative Look at Hun and Mongol Military Technologies | The Silk Road. (n.d.). Edspace.american.edu. https://edspace.american.edu/silkroadjournal/v16_2018_rumschlag/

Ramirez, J. E. (2000, April 10). Genghis Khan and Maneuver Warfare. Defense Technical Information Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA378208#:~:text=Genghis%20Khan%20developed%20a%20military,to%20those%20of%20his%20enemies

Raphael, K. (2009). Mongol Siege Warfare on the Banks of the Euphrates and the Question of Gunpowder (1260–1312). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 19(3), 355–370. doi:10.1017/S1356186309009717

Yang, Q. (2019). Like Stars in the Sky: Networks of Astronomers in Mongol Eurasia. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient.

Images:

“Mongol Archer” by Stonnefrety7777 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

“Silk Road – Public domain copyright free geographic map” is in the Public Domain

“Mansur1911-Publicdomain documentscanofdrawing” by WikimediaCommons is in the Public Domain

AI ACKNOWLEDGMENT:

I used Microsoft Copilot to condense this chapter. It also created an outline for the chapter which gave me topics to write about. For example, it gave me “Infrastructure and Communication” so I chose to research the Silk Road and the Yam system.