Medieval (about 476AD-1600’s)

22 The Black Death & the Unexpected Benefits to Society

Rachael Levine; Zoë Lovelock; John Stephenson; and Isabelle Martinez

introduction

introduction

The Black Death was a devastating bubonic plague that struck Europe in the mid-1300s. The sickness came with boils and black skin that took over the body and slowly killed its victim. The plague killed two-thirds of Europe’s population after it entered Europe for the first time in October of 1347 through ships docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. The first countries to be hit with the plague included China, India, Persia, and Egypt (History.com Editors, 2010). Lack of effective sanitation caused increase rat populations in large cities, in turn promoting flea increase; all creating the perfect scenario for spreading a contagious disease (Clay). The onset of the black death took medical practitioners by surprise, including those who claimed to be experts in disease control. No plague to this degree had ever entered Europe, and it quickly claimed the lives of those who seemed perfectly healthy before the outbreak. People quickly turned on each other, becoming quick to blame minority groups such as Jews, foreigners, travelers and lepers, which resulted in vast social and economic havoc. The outbreak of the Black Death in the mid-1300s left most of the Western European civilization in a devastated state. However, the medical response resulted in discoveries such as quarantine and the creation of medicines that combated the deadly plague. This devastating event led to many changes in the world, including the innovation and advancement of modern medicine and the fall of strong economic systems that shaped the world’s future. These impacts make the Black Death one of the most influential periods for STS.

The symptoms and spread of the plague

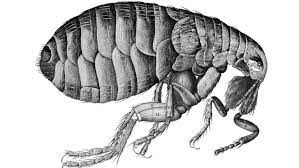

The Black Death was one disease that ravaged throughout all of Europe, taking many lives. The symptoms were highly gruesome and many led to unexpected deaths; causing panic and unrest among populations. These include swellings and boils all over the body, diarrhea, fevers, aches and pains. Many believed the disease was due to some invisible force, like spirits, due to its quick and powerful spread. However, in reality this was due to the vast range of spreading agents the plague relied on. Rats became the most influential host for the demise of the human population. Anywhere human populations were infected, there were rat populations nearby. However, just like human populations, rats were victims of infection by the main causative agent- bacterial pathogen, Yersinia Pestis. Colonizing in the blood streams of rats, Yersinia Pestis, was then allowed to spread to other rats through blood meals from fleas. This process quickly infected populations of rats at alarming rates, making them the main carrier for this disease. Humans became accidental hosts for this disease through flea or rat bites from infected carriers. Due to the lack of resistance to the Plague many humans who were infected died within 5 days after first symptoms appeared. The presentations of the Plague include swollen lymph nodes and black splotches on fingertips and the nose. This darkening of skin is why the Plague became known as the “Black Death”. Death can come from multiple different ways including septicemia from internal hemorrhaging, bursting of buboes through skin and, the worse, pneumonic plague. During this time there was no cure, which made this disease one that brought lots of terror and fear.

Quarantine then

As the outbreak of the century began to tear through the European population, doctors were desperate to find a cure for the harmful epidemic. As the plague began to kill almost a third of the European population, medical experts developed some methods to try and stop the Black Death from spreading more. One of the tactics that was discovered and utilized was quarantine. Quarantine is separating or isolating those suspected of carrying a deadly disease. Quarantining was implemented on a vast scale when seaports were blocked off, prohibiting imports and exports from entering or exiting the country. First, it started in the Italian ports because the plague was thought to have entered Europe from one of the ships that docked in Messina. This method was, in theory, successful; however, after the first infected person set foot on land, others were immediately infected. There was no way to stop the plague from moving farther inland by only closing off the seaports. To use this new tactic of isolation, Italian and Croatian officials created sections of town where people who were ill or suspected of being ill were forced to stay. These efforts proved only slightly effective, so additional laws were implemented, such as the “Trentino or thirty days isolation period.” This required all infected persons to remain isolated for 30 days before entering Ragusa, the central town in Sicily (Mackowiak, 2002). This newly developed medical practice improved the death toll and gave hope to doctors and practitioners that this containment method would continue to work in the fight against the plague.

Quarantine now

Quarantine is still used worldwide to control events such as the Ebola outbreak in the United States in 2014 and even in 2020 with Covid-19. When the first person was exposed to the disease, they went under observation and remained in quarantine until it was safe to leave the hospital. There were no other reported cases of Ebola since that person was released in 2014. With Covid-19 however, it was extremely long and dangerous, but many died from this and it was a worldwide disease. Quarantine is continuing to be utilized in situations that parallel that of a massive disease outbreak and has proven to be just as successful as it was in the 1300’s when the Black Death struck Europe.

Medicine

Before the Black Death, medicine was in simple forms, consisting of roots, flowers, herbs, etc, that apothecaries would combine to create remedies for specific illnesses or medical issues. Most people did not question the system until the Black Death came along. When patients came in with the symptoms of the plague, doctors treated them with the methods they had used for years but soon found that those did not work. They came up with new, somewhat barbaric treatments to treat the severe symptoms. For example, doctors would burst open the puss bubbles that formed on the infected person and drain them of everything inside the wounds. As described in Gottfried’s (1983) The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe, doctors said:

“If an ulcer appears… near the ear or the throat, take blood from the arm on that side, that is, from the vein between the thumb and the first finger… But if you have an ulcer in the groin, then open a vein in the foot between the big toe and its neighbor… at all events, bloodletting should be carried out when the plague first strikes.

“At all events, bloodletting should be carried out when the plague first strikes.”

By draining wounds, doctors felt it would rid the person’s body of any infections bacteria. Along with draining, patients were told to sit by a hot furnace or fire to “drove out the disease.” (p. 3).

This particular method of draining did prove to be beneficial in terms of getting the infectious bacteria out of the pus wounds, however, when the patient’s wounds were drained, they lost copious amounts of blood that only harmed them in their effort to recover. Modern medicine does have some connections to the method of draining, as doctors today will draw small amounts of blood to run tests to determine what strains of bacteria are in the body. This helps doctors identify what sickness, disease, etc the patient has contracted and what medicines can be used to treat a particular strain.

Fall of feudalism

Two-thirds of the overall population got infected by the Black Death, half of them dying. This infection hit peasant populations the most, leaving much of the upper classes to pick up the repercussions after the Black Death ended. Due to the feudal system, many nobility were unsure how to use the skills and professions usually kept by the lower class. These included tending to crops and production of goods. Upper-class people needed new workers in these fields and, therefore, agreed to pay higher wages to the class above the previous peasant class, which were previously not paid at all. This new class, known as the merchant class, vastly differed from what was before them. The merchant class made money from their work, whereas the previous peasants exchanged work for a place to live. This shift in working low-class jobs for pay changed the whole economic structure of Europe (Clay).

The results were also positive in the merchant classes’ favor in terms of social issues. Previously, the feudal system was highly rigid and allowed no mobility between classes or changes in lifestyle. Not only had this rising class brought an end to the upper classes’ firm grip on the lives of all of Europe, but they also fostered new conditions through continuous revolts. These further weakened the authority of the feudal lords.

medieval society and the plague

The part of society that the Black Death and its medical discoveries impacted the most was the common civilian, more than likely someone of low income and limited access to valuable resources. This demographic was targeted by the disease more than others because these citizens did not have access to resources such as private baths or clean water that upper-class citizens did. This lack of availability resulted in poor hygiene, leaving the lower class more susceptible to disease. The plague itself had the most impact on the European community in the 1300’s, however, the results of the plague had a global impact. Following the destruction of the Black Death, the discovery of quarantine provided a gateway for advanced medical practices to be used around the world inspired by the new technique. The science and technology that was prominent during and after the Black Death consisted of advancements in the medical field along with new ways of thinking that paved the way into the Renaissance. For example, ideas from intellectuals who studied the causes of the Black Death stemmed from ancient sources that said “Physicians could cast retrospective horoscopes to identify the configurations of the planets that had caused diseases and epidemics. Physicians also had to incorporate the astrological concept of the “medicinal month” into their plans for treatment of the patient.” (Astrology and Medicine, 2019). There was less of a tangible technological aspect involved in the aftermath of the Black Death, but more so scientific discoveries that contributed to the “general knowledge bank” for further doctors and medical experts to use in the future. The Black Death and its benefit to society are more closely related to science than technology because the medical practices that were created utilized scientific research more than technological advances.

ANECDOTAL AND HISTORICAL BELIEFS DURING THE TIME OF THE BLACK PLAGUE

In some ways, unscientific or anecdotal ideas were common beliefs during the centuries that the Plague influenced Europe. One central idea was the theory of Miasma, which the people used to find out why all this was happening and why they were suffering. Miasma was seen as an air that could infect a person with diseases and plights caused by divine providence or otherworldly powers (Slack 433). Viewing Miasma as a result of godly intervention plays into the polarizing nature of religion at the time. Some chose to forgo the burdens of traditional religious beliefs in the face of the fleeting nature of plague life. In contrast, others became extremely pious, seeking refuge in Christianity as a means of salvation. At the time, it also tried to explain why some towns saw a more significant impact from the Plague than others; the Plague was god’s punishment for sins committed by the town/city folk.

Of course, the transmission of the Plague was due to plague-carrying fleas who would jump from person to person or animal to person and vice-versa. However, some ideas about Miasma did lend themselves to modeling the transmission of the Plague via some hosts. For example, it was common knowledge that Miasma could be transported by sick persons from place to place, not only on the sick persons but also on their belongings and people and objects around them (Slack, 435). In this way, notions of avoiding sick persons (quarantine) and attempts to curb the spread of the Plague via travel or other spatial restrictions were adopted and employed. While Miasma was not a real occurrence, it did somewhat model the dynamics of the actual transmission of the Plague. Miasma would not largely be disproven until the foundation of Germ Theory, largely attributed to the work of French scientist Louise Pasteur in the mid-19th century (Louis Pasteur, 601).

While some improvements in medical practice and knowledge did occur during the Black Plague, regimens to prevent plague and other pestilences that took influence from pre-plague practices largely stayed the same for the next few centuries. For example, bloodletting, the practice of cutting a patient to allow blood with bad “humour” or disease to be released from the patient, continued into the Victorian era. However, this practice ultimately weakened the patients, making them more susceptible to the disease they were battling due to blood loss (Fabbri, 248).

Increasing an area’s ventilation was also thought to reduce the spread of the plague since it was believed to spread via miasma. Creating outdoor fires and using incense were also employed (Fabbri, 249), but they were ineffective since fleas spread the plague. Other means included religious practices. Joshua Mark states in his article Medieval Cures for the Black Death that “Religious cures were the most common and, besides the public flagellation mentioned above, took the form of purchasing religious amulets and charms, prayer, fasting, attending mass, persecuting those persons thought responsible, and participating in religious processions” (Medieval Cures for the Black Death, 2020).

Ultimately, some of these practices went away over time, such as the public flagellation after the pope decried its usage and the purchasing of religious artifacts during the reformation of the Catholic Church. Some practices, such as bloodletting, continued long after the plague first appeared. However, previously discussed methods such as quarantines and medical isolation did come to prominence and were widely used to curb the spread of disease.

Chapter Questions

Multiple Choice: Which of the following medical advancements was not mentioned as a result of the Black Death outbreak?

a) Health-facilitating hygiene practices

b) Amputation

c) Blood testing

d) Quarantine

Multiple Choice: Which group of people was affected the most by the Black Death?

a) Common Civilian

b) Army

c) Governing officials

d) Upper-Class Civilians

Short Answer: List at least three methods doctors used to manage the outbreak of the Black Death.

Short Response: Which medical practices used during the Black Death show to be similar to modern practices? How are they similar?

Short Response: Was the loss of life during the Black Death worth the advancements for the future? Why or why not?

references

Astrology and Medicine. (2019, November 13). Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/astrology-and-medicine.

Gottfried, R. S. (1983). The Black death: natural and human disaster in medieval Europe. San Diego, CA: Lucent Books.

History.com Editors. (2010, September 17). Black Death. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/black-death.

Mackowiak, A., P., Sehdev, & S., P. (2002, November 1). Origin of Quarantine. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/35/9/1071/330421.

Slack, P. (1988). Responses to Plague in Early Modern Europe: The Implications of Public Health. Social Research, 55(3), 433-453.

Conn, H. (1895). Louis Pasteur. Science, 2(45), 601-610.

Fabbri, C. (2007). Treating Medieval Plague: The Wonderful Virtues of Theriac. Early Science and Medicine, 12(3), 247-283.

Mark, J. (2020, April 15). Medieval Cures for the Black Death. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 13, 2021, from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1540/medieval-cures-for-the-black-death/.

Shipman, P. L. (n.d.). The Bright Side of the Black Death. Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-bright-side-of-the-black-death

Spyrou, M. A., Musralina, L., Gnecchi Ruscone, G. A., Kocher, A., Borbone, P.-G., Khartanovich, V. I., Buzhilova, A., Djansugurova, L., Bos, K. I., Kühnert, D., Haak, W., Slavin, P., & Krause, J. (2022, June 15). The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century Central Eurasia. Nature News. Retrieved October 9, 2022, from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04800-3

Clay, M. (n.d.). Drop Dead Feudalism. University of Denver. https://clas.ucdenver.edu/nhdc/sites/default/files/attached-files/entry_147.pdf

images

Figure 1: “The plague of Florence in 1348” is licensed under CC BY 4.0