Renaissance/Enlightenment (1600’s-1800’s)

34 The Pseudoscience Behind Witch Trials

Margaret Hall; Alexandra Harrington; and McKenzie Bradley

Introduction

Tens of thousands of people, the majority women, were tried and executed under the false claim of being witches between 1450 and 1750 in Europe (Wallenfeldt, 2018). These witch hunts were deeply rooted in fear, superstition, and social control, targeting marginalized individuals who deviated from societal norms. Witchcraft accusations often stemmed from personal grievances, rumors, or unexplained events, and were exacerbated by religious fervor and political instability. The trials relied on pseudoscientific methods to validate claims of witchcraft, further reinforcing the persecution of innocent individuals.

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 in colonial Massachusetts marked one of the most infamous chapters in the history of witch hunts. These events unfolded against a backdrop of widespread fear and tension in the Puritan community. Factors such as extreme weather conditions, a smallpox epidemic, and ongoing conflicts with Indigenous peoples created fertile ground for paranoia (Salem Witch Museum, n.d.). The trials began when Reverend Samuel Parris’s daughter and niece exhibited mysterious symptoms that were attributed to bewitchment by the village doctor (García, 2022). Over 200 people were accused of practicing witchcraft, with 20 executed and many others imprisoned under harsh conditions (New England Law, 2024).

The phenomenon of witch hunts was not unique to Salem but rather a continuation of practices that had swept through Europe for centuries. Between 1400 and 1775, approximately 100,000 people were prosecuted for witchcraft across Europe and British America, with an estimated 40,000 to 60,000 executions (Wallenfeldt, 2018). These hunts often targeted women who were seen as social outcasts or threats to patriarchal structures. Accusations ranged from consorting with the devil to causing illness or crop failures through supernatural means. The trials relied heavily on methods such as identifying “Devil’s marks” or using spectral evidence—concepts that lacked any scientific basis but were considered legitimate at the time (Gaskill, 2015).

The Salem Witch Trials serve as a stark reminder of how pseudoscience can be weaponized to justify persecution and consolidate power. In Salem, spectral evidence—claims that a witch’s spirit could harm others—played a central role in convictions until it was disallowed by the Superior Court of Judicature (Van Engen, 2016). This reliance on unprovable claims highlights how fear and ignorance can override rationality and justice. The trials reflect broader societal patterns seen during European witch hunts: the use of pseudoscientific practices to scapegoat vulnerable populations during times of crisis.

COnnection to STS

The Witch Trials, both in Europe and the United States, are a prime example of the effects that science and technology can have on society. Although different from the physical, observable evidence that today’s justice system requires, all of the tests conducted throughout the witch trials that we will see in this chapter were based on spectral evidence. It was their own initial justice system that has continued to be redefined to the strict system we have in place today. Additionally, these tests can be regarded as technology during the aforementioned time periods. At the time, the public believed these tests were rooted in science. However, this treatment was based on fear and the need for control, greatly influenced by the social, political, and religious environmental upheaval. When the public is scared, starving, or in any type of turmoil, the people in charge will be quick to blame a victim other than themselves. This science and technology was used to control society and propagate the people in power’s rule. The witch trials underscore the importance of moral and ethical values and standards within the field of science and the justice system.

The Social, Political, and Religious Foundation of the Witch Trials in the United States

The era of the Salem Witch Trials was marked by uncertainty, stemming from political instability, economic hardship, and religious paranoia. The Glorious Revolution of 1689-1690 in England had established major European conflict, particularly war with France, that stirred up conflicts in New England between the settlers and American Indians. Governor Edmund Andros’ government in Boston was overthrown in 1689 following the Glorious Revolution in England, so Massachusetts lacked a legally established government with no governor nor a royal charter for about three years until a royal governor was established in 1692 (Ray, 2010). Additionally, the federal judicial system was not enacted until 1789 under the Federal Judiciary Act (National Archives and Records Administration, 2022). Before this law, the legal system did not require strict evidence which plagued the trials. The judges of Salem relied upon spectral vision in which people would reenact the “fits” they claimed to witness among the suspected women in order to legitimize arrests (Ray, 2010). Nonetheless, a sense of fear, insecurity, and danger had disturbed the New England region. European settlers had brought smallpox to North America in the 17th century, contributing to many economic uncertainties.

One of the first women to be accused of witchcraft that initiated the beginning of the Salem witch trials in 1692 was Tituba, an American Indian slave of Reverend Samuel Parris, an appointed minister of Salem. It is believed that Tituba would share stories of witchcraft, perform spell-like rituals, and engage in fortune telling for Parris’ young daughter and her cousin which frightened them. It is also believed, however, that Tituba’s story was a folktale dating from the eighteenth century into the nineteenth century, and young girls were deemed “afflicted” persons because they partook in fortune telling. Tituba’s story demonstrates the religious hysteria that contributed to the trials. Parris’ Puritan work was marked by inflammatory sermons, dividing the church community between the “chosen” and the “ wicked and unconverted”, preaching against Satan’s attack and betrayal on his ministry. Witchcraft, in particular, was viewed as a threat to Parris’ work and became viewed as a largely Satanic plan to destroy the New England churches (Ray, 2010). Puritan beliefs, including their strong belief in the Devil, sin, damnation, and strict religious doctrines, played an important role in the mass hysteria of this time, stirring up a climate of fear and uncertainty.

Together, the social, economic, and religious factors contributed to the turmoil and upheaval that plagued New England during the era of the Salem Witch Trials.

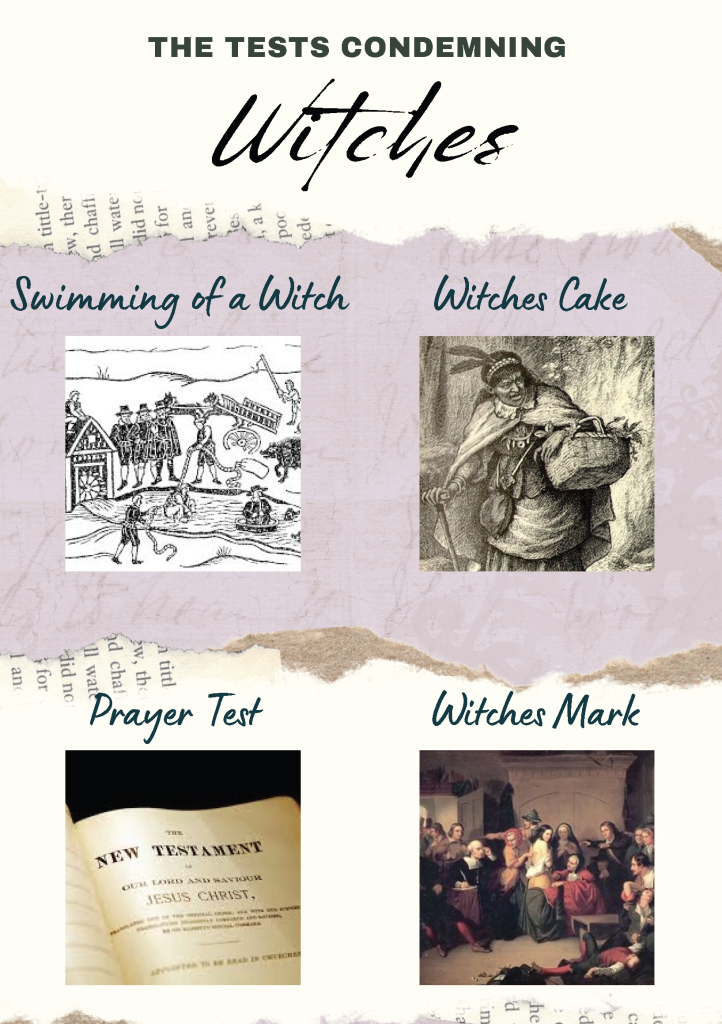

The tests that condemned witches

Swimming of a Witch: One of the most known tests to determine who was a witch is the “swimming” of a witch. This was used across Europe and America during a period when religion was closely intertwined with science (Dorn, 2022). This belief stemmed from the idea that water, as a pure element, would reject witches, causing them to float. Furthermore, the prosecutors believed if the witch floated, God was interfering and creating a miracle to tell them she was guilty. This trial was used for multiple types of crimes that could not have a fair trial for reasons such as no witnesses.

Witches Cake: The use of the witches cake in Salem was one of the earliest tests conducted during the trials, exacerbating hysteria when it failed to produce results. A cake is made using a victim’s urine and rye meal. This is then fed to a dog who will also become afflicted with “fits” if the victim is possessed by a witch (Caporael, 1976). Pictured in the infographic is Tituba, an enslaved Native American living in Salem in 1692 (Boomer, 2024). She was asked by a church member to bake this witches cake and was later prosecuted as a witch and murdered for following the church members orders.

Prayer Test: Another test commonly used was the Prayer Test. This was famously used in 1664 England to persecute Amy Denny and Rose Cullender. Amy and Rose were responsible for the care of children who kept having “fits”. The test involved the children reading an excerpt from the New testament. When either of the girls came across the word Lord, Jesus, or Christ they fell into a fit. When they came across the words Satan or Devil they would say, “This bites but makes me speak right well”. The inability to recite sacred words without fits was interpreted as evidence of demonic possession, reflecting the era’s deep intertwining of religion and law. We would now blame this on autosuggestion- a type of self hypnosis due to the placebo effect (Riddell, 1926). At this time however, it was the clear sign of possession and witchcraft by Amy Denny and Rose Cullender and led them to being hanged on March 17, 1665.

Witches Mark: The witches mark were “physical marks on witches clearly visible to the naked human eye” (Dunn, 2017). In the early modern period of Europe, the church used this test to verify with physical evidence that the accused was in fact a witch. They believed this provided non disputable evidence. The marks, also well known as “Devil’s Marks” could be anything from a freckle or mole, to an extra nipple or tattoo. The identification of witches’ marks exploited natural skin variations, reflecting a broader cultural fear of bodily difference as a sign of evil.

Conclusion and connection to Sts

By examining the pseudoscience behind witch trials, we gain insight into how fear can distort perceptions of science and technology. The tests used to identify witches, including the swimming trials, witch’s cake consumption, the prayer test, and physical marks on the body, were considered scientific advancements at the time, although rooted in superstition rather than empirical evidence. The Salem witch trials were not driven solely by superstitious beliefs, but rather were the result of deeply rooter social tensions, political instability, and religious upheaval. These methods illustrate how societal anxieties can shape scientific practices and lead to devastating consequences for those deemed “other.” Understanding this history is crucial for recognizing similar patterns in modern contexts where pseudoscience continues to be used as a tool for discrimination and control.

Citations

Boomer, L. (2024, February 27). Life story: Tituba. Women & the American Story. https://wams.nyhistory.org/early-encounters/english-colonies/tituba/#resource

Brand, C. (2022, October 19). The malleus maleficarum: A 15th century treatise on Witchcraft – University Libraries: Washington University in St. Louis. University Libraries | Washington University in St. Louis. https://library.wustl.edu/news/the-malleus-maleficarum-a-15th-century-treatise-on-witchcraft/#:~:text=Scholars%20estimate%20that%20approximately%20110%2C000,the%20trials%20ending%20with%20execution.

Caporael, L. (1976) Ergotism: The Satan Loosed in Salem. Science, New Series, Vol. 192, No. 4234 (Apr. 2, 1976), pp. 21-26 DOI:10.1126/science.769159

Dunn, S. (2017). “The mark of the Devil : medical proof in witchcraft trials.” . Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2804.

https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2804

Dorn, N. (2022). Swimming a witch: Evidence in 17th-century English witchcraft trials: In Custodia legis. https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/02/swimming-a-witch-evidence-in-17th-century-english-witchcraft-trials/#:~:text=Witch%20swimming%20was%20the%20practice,floating%20indicated%20a%20guilty%20verdict.

García, K. (2022, March 11). Possessed: the Salem Witch Trials. Penn Today; University of Pennsylvania. https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/possessed-salem-witch-trials

Gaskill, M. (2015). The Salem Witch Trials. Bill of Rights Institute; Bill of Rights Institute. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/the-salem-witch-trials

National Archives and Records Administration. (2022, May 10). Federal Judiciary Act (1789). National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/federal-judiciary-act

New England Law. (2024). A True Legal Horror Story: The Laws Leading to the Salem Witch Trials. Www.nesl.edu; New England Law Boston. https://www.nesl.edu/blog/detail/a-true-legal-horror-story-the-laws-leading-to-the-salem-witch-trials

Ray, B. C. (2010). “The Salem Witch Mania”: Recent Scholarship and American History Textbooks. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 78(1), 40–64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40666461

Riddell, W. R. (1926). Sir Matthew Hale and Witchcraft. Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology, 17(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.2307/1134305

Salem Witch Museum. (n.d.). Witch Trials Memorial. Salem Witch Museum. https://salemwitchmuseum.com/locations/witch-trials-memorial/

Van Engen, A. C. (2016). The Salem Witch Trials. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.139

Wallenfeldt, J. (2018). Salem witch trials. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Salem-witch-trials

Image Citations

Ehninger, J.W. (1902) Tituba [Illustration]. The Complete Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tituba-Longfellow-Corey_(cropped).jpg

Matteson, T. (1853) The Examination of a Witch [Painting]. UChicago Library. https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/about/news/the-salem-witch-trials-a-legal-bibliography-for-halloween/

United Church of God. (2011) The New Testament [Image] UCG. https://www.ucg.org/bible-study-tools/booklets/the-ten-commandments/the-ten-commandments-in-the-new-testament

Unknown (1615) The Swimming of Mary Sutton [English Woodcut Print]. Witches Apprehended. How Lyme Disease Created Witches and Changed History.

Wyman. (2014, October 21). The Salem Witch Trials, The Clergy, and Their Families: A Fascinating Infographic | Walking Together Ministries. Walkingtogetherministries.com. https://www.walkingtogetherministries.com/2014/10/21/the-salem-witch-trials-the-clergy-and-their-families-a-fascinating-infographic/

AI ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Perplexity AI was used to help find information about the pseudoscience behind witch trials that fits the goals of this textbook chapter. AI provided summaries of historical events and pseudoscientific practices, connections between witch trials and broader societal implications, and reliable references that were then manually reviewed and incorporated into the chapter. All AI-generated outputs were critically evaluated, edited, and supplemented with additional research from non-AI sources. The final content reflects a combination of AI assistance and human expertise. (2025) Perplexity AI [Large Language Model]. https://www.perplexity.ai/